IT was the biggest gang trial in Sydney’s history, so why weren’t security staff ready when the accused men in the dock started trying to kill one another?

The most likely scenario is that he’d hid the blade in his mouth before departing Parklea Correctional Centre in a prison van that morning, somehow making it past handheld security wands, a walk-through metal detector and a strip search before his arrival at court.

And yet none of these measures stopped Javad bringing the weapon into the reinforced dock and lunging at the Qaumi brothers, landing a punch but dropping the blade as security officers swarmed.

Unclear too is why he wanted to attack the brothers on February 12 this year, though police suspect one motivating factor was a phone call intercepted months earlier between Mumtaz Qaumi and another inmate, Mahmoud Atwa, which suggested a burgeoning murder plot.

Mumtaz hardly cared that Javad owed Atwa and his associates $7000, or that Atwa was talking about killing Javad in prison; but he was concerned about the consequences.

“If he [Javad] survives he’s gonna snitch on all of us, hey,” Mumtaz said. “If you’re gonna get him,” he continued, “don’t call out to him through the fence, because then he’s gonna know something’s up, yeah? Don’t give him heads up … do what you’ve got to do in the showers.”

Transcripts of these calls made their way back to Javad during pre-trial hearings in February this year when Justice Peter Hamill — the arbiter of this landmark case — was deciding what evidence should and shouldn’t be used against the Qaumi brothers, setting the stage for what would soon become known as the “BFL megatrial”.

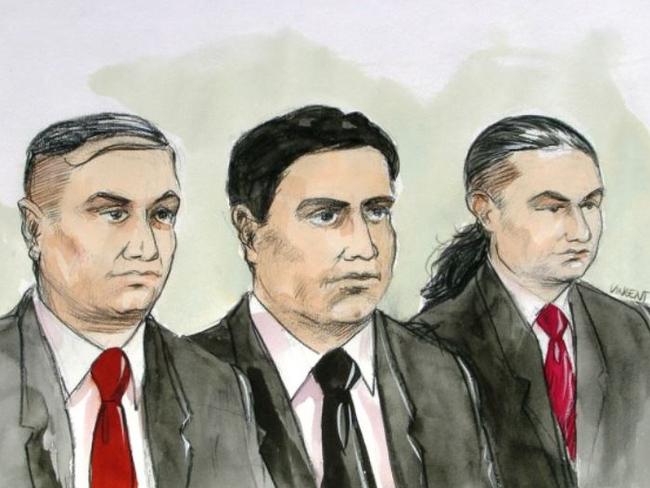

At the start of these hearings there were nine people in the dock but, after some deal-cutting and early guilty pleas, the number dwindled to five — the Qaumi brothers plus Javad and Mohammed Kalal, the only Lebanese member of the Blacktown BFL.

Don’t give him heads up … do what you’ve got to do in the showers.”

The jury of 15 — eight women, seven men — were deliberately shielded from hearing about Javad’s incident in the dock and the phone call that apparently prompted it. Nor were they told about numerous other courtroom subdramas that arose during the seven months of hearings.

They weren’t told that a juror colleague was discharged for repeatedly flirting with Farhad and Mumtaz in the dock, throwing smiles and coquettish nailbiting in their direction.

They weren’t told why a Perspex barrier was suddenly installed to separate the Qaumi brothers from their co-offenders, or about the incident that prompted its arrival, which was captured on video — the CCTV footage shows Mumtaz slyly grabbing a pen and lunging at co-offender Kalal less than a metre away, using the pen to stab at his chest and neck in full view of Justice Hamill and a phalanx of security staff who, caught slightly off guard, restrained the men in seconds.

Evidence of thinly-veiled threats made by the Qaumi brothers were also kept from the jury for fear it may prejudice their decision-making. Detective Inspector Glen Browne, lead investigator on the Hamzy murder, told the court there was evidence Mumtaz Qaumi had wanted to delay the trial so the prosecution would “lose some of its ‘roll over’ witnesses,” a statement which Justice Hamill found basically amounted to arranging murders.

Most of these witnesses/informants — twelve in total — were former gang lieutenants like Ramin, Pouria, Ario and Vayu, all of whom agreed to give blow-by-blow accounts of each shooting to Strike Force Sitella and Roxana investigators in exchange for generous sentencing discounts and benefits for their co-operation.

Protecting these witnesses was its own sub-drama of lengthy legal argument and risk assessment. Many wanted to give evidence via video-link from remote locations due to safety concerns. One said he might feel physically ill or faint at the sight of the Qaumi brothers. Another said: “Unless you have been around the Qaumis and BFL you don’t understand how crazy they are.”

A plot was uncovered to murder two investigators and there were tense moments when Jamil Qaumi refused to answer questions in the witness box about whether Javad had accompanied him on the night of the Hamzy murder at Revesby Heights.

You don’t understand how crazy they are.’’

He was happy to confirm Ario’s presence and his own, but stopped short on Javad.

“I’m very sorry, your Honour, but I can’t answer that question.”

“I am not interested in your apology. I am asking whether you are refusing to answer the question?”

“Yes, your Honour.”

Four charges of perjury were subsequently added to his slew of offences.

This all went down in what can only be described as a very sleek and modern courtroom, a realm of designer lighting, honey-coloured timber, flat screen TVs and a surfeit of working microphones.

Sawn-off shotguns and pistols seized by detectives were brought into court and shown to the jurors; private phone calls between gangster heavyweights were played in lurid detail; folders of confidential witness statements, ballistic charts, medical records and intercepted text messages crammed every available shelf space, along with a box with the word “SHRED” written in black texta on its side.

Due to the number of charges and complexities of each one, early estimates suggested this would be one of the longest trials in recent memory. Seven months of hearings took the trial towards record-setting territory, a benchmark set by the gargantuan Pendennis terrorism trial of 2009, which sat for a mind-bending 11 months. On day 100 Justice Hamill handed out 10 bottles of “BFL” branded pinot noir — one to each barrister, the prosecutor, and the rest to select court staff — paying for them himself.

Taxpayers would be right to ask themselves what it costs to turn these wheels of justice. The jurors alone received $210 per day, which amounted to nearly $400,000 in payments by the time the verdicts were handed down. The beefed-up security presence in court each day and the transport costs are also expected to bump up the final bill.

But the greatest fees were, of course, commanded by the five defence barristers who were each paid for by Legal Aid NSW. Their hourly rate remains neither clear nor exact, but one, speaking on the condition of anonymity, estimated an eventual payout of roughly $700,000.

At a conservative estimate, the cost of running the case will end up being in the neighbourhood of $5 million.

The news of the BFL’s demise was delivered at a press conference by Deputy Commissioner Nick Kaldas the day after Qaumi’s arrest.

“In many ways, this is just the beginning,” he said. “We pretty much know what has happened with just about all of the shootings that have occurred in the last 12 months.”

Like every great investigation, the detectives who trawled through days of camera footage, who convinced informants to do the right thing, who spent hours taking statements and withstood death threats — they received little public acknowledgment.

Expectations were high that defeating the BFL would help cement Kaldas’ prospects of becoming the next commissioner, though this was not to be.

Not long after Qaumi’s arrest, Commissioner Scipione announced he, Scipione, would stay in his role for another year. “There’s more to be done,” he said, cryptically, without saying much else.

That was March 2014. Two months later, Premier Barry O’Farrell and Police Minister Mike Gallacher, Kaldas’s two key sponsors, would stand aside from their posts amid a donations scandal engulfing the Liberal Party.

Still seething over the decades-old bugging scandal, Kaldas would end up giving evidence in parliamentary hearings that lobbed mortar rounds at rival deputy Catherine Burn and, briefly, brought the NSW Police Force into disrepute. The saga appeared to ruin both of their immediate chances as leadership contenders.

In early 2016, Kaldas left the NSW Police Force. He’s since made it clear he would love to return as Commissioner one day. Burn, who has since been given back responsibility for the State Crime Command, and Scipione, who says he will retire in 2017, remain in their jobs.

‘Worthless’: Sports clubs’ sobering child safety warning

Child safety experts have delivered a confronting verdict on background checks and reporting systems after Sport Integrity Australia complaints data revealed junior sport's hidden dangers.

What the fox? Why viral clothing brand is under fire from Gen Z

Frustrated shoppers have unloaded online after buying clothes from one of Australia’s most coveted brands, with claims quality has gone ‘down the drain’. See the pictures.