TWO passionate, ambitious killers running rival armies within the same gang: what could possibly go wrong?

Most importantly, they needed approval to visit him in Supermax. His visitor list was a tightly-managed process because of his high-risk status and track record for scheming — an elderly aunt once had to wait 18 months before she was granted visitor status.

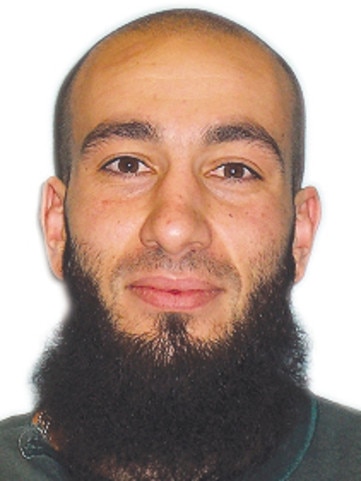

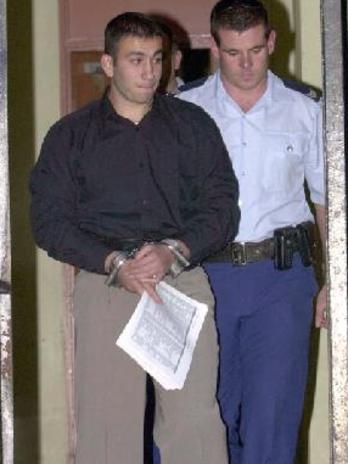

Hamzy basically rewrote the rulebook for how inmates needed to be managed. He first arrived in prison in 1999 to face trial for the murder of a man outside the Mr Goodbar nightclub in Paddington.

From his cell he tried to arrange the murder of a Crown witness in his case, a plot that failed because the hitman was working for police. He received a 21-year sentence for his crimes, becoming deeply religious in prison as the years flowed into each other, learning Arabic and nurturing his piety by listening to Koranic tapes.

By 2007 prison officers accused him of forming a jihadist gang in Supermax. They’d seen non-Muslim inmates, some of Indigenous heritage, converting to Islam, growing out their beards and kneeling before Hamzy to kiss his hand in the corridors. He was moved to Lithgow where, within months, he was charged with masterminding a drug syndicate sending kilos of ice and cannabis between Sydney and Melbourne, organising kidnappings in Melbourne and Adelaide, and arranging drive-by shootings using a phalanx of loyal soldiers.

Ramin would later tell police that by 2013 Hamzy was using an intermediary, “The Runner’’, to pass on messages to his two chapter leaders outside of prison.

The Runner became a diplomatic back-channel to the Blacktown and Bankstown chapters, a mouth-piece for Hamzy, a position of tremendous power.

“Bass had no clue what the fuck was going on,” a BFL member would later tell police. “[The Runner] was just making up ... shit, that’s what it looked like to me.”

It was also The Runner’s job to pass messages between Qaumi and LC, both of whom rarely spoke to each other. This arrangement might have seemed sensible at first, but it would eventually lead to a raft of perceived slights, wounded egos and a build-up of tension between the gangs.

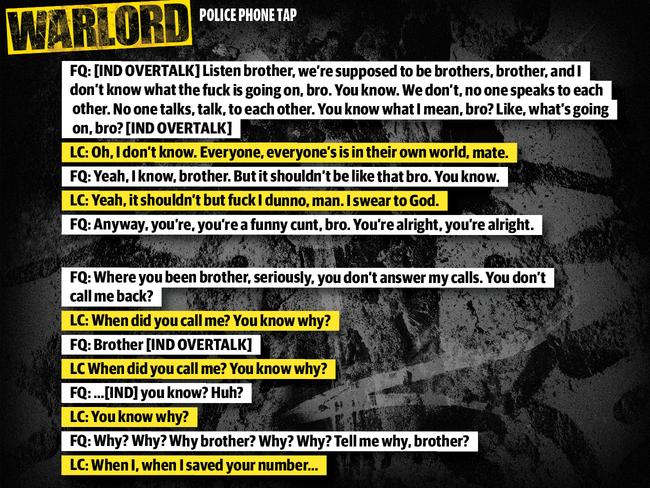

On one rare occasion when Qaumi spoke to LC, he complained about their lack of cooperation.

“I don’t know what the fuck is going on, bro. You know,” Qaumi began. “No one speaks to each other. No one talks to each other. You know what I mean, bro? Like, what’s going on, bro?”

“Everyone’s is in their own world, mate,” LC replied.

“Yeah, I know, brother. But it shouldn’t be like that bro. You know”

Qaumi’s top priorities during those first few weeks of gang formation were to build up drug turf and acquire more guns. He’d squirrelled away a modest arsenal of weapons — three pistols, two sawn-off shotguns, an SKS assault rifle he’d bought off an old bikie for $4000 — but he needed more weapons and more turf in order to solidify his presence in the south west.

He turned to LC for help but got snubbed — the Bankstown leader flaked on a deal to deliver some promised firearms; later he rejected Qaumi’s bid for a slice of Bankstown’s turf.

LC said he could have Granville to Penrith and basically laughed off the request.

The relationship seemed to break down from there.

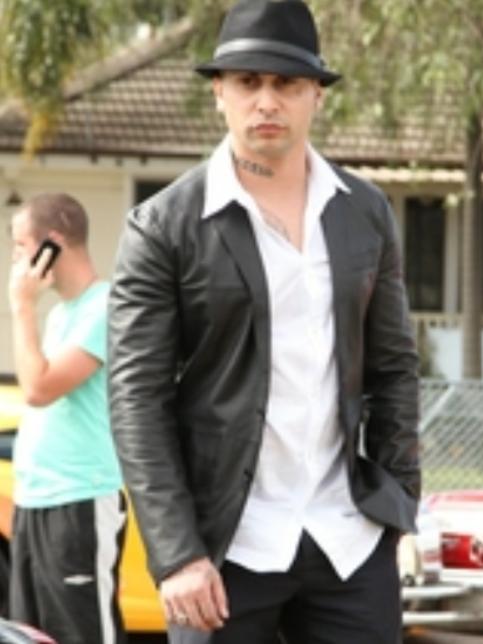

Qaumi grew bitter of LC, his luxury cars that changed each week, the diamond in his earlobe.

He begrudgingly made do with the drug territory he was allocated, sending dealers out on cannabis and ice runs through his patch of the western suburbs. On the weekends these dealers would head into the city and work the gay bars of Oxford Street, Paddington, or the nightclubs of Kings Cross, all of which were, by convention, open to anyone for street dealing.

Qaumi would turn a $5000 drug investment into a $15,000 return by buying an ounce of ice from the Hamzy family or Lone Wolf bikie gang and then selling it to members of his own crew at a profit. They would then dilute the drug with Lignocaine, the dental anaesthetic — a process known as “jumping” — and then sell it in street deals at a marked-up price. The profits would all go back to Qaumi.

But even under this arrangement, he was still perpetually short of cash, borrowing off friends to buy luxury items. Someone had to lend him the money when he found an expensive watch he saw in Bondi Beach.

Under this pressure, Qaumi floated the idea of taking over the BFL.

“I should take over the whole thing,” Qaumi said, according to Ramin. “I’ve got the name and stuff.” (Qaumi would later deny these words were ever spoken.)

Ramin agreed in a kind of placating, shoulder-shrugging way that Qaumi took more seriously that he should have. He started forming strategies to topple LC, asking Ramin to conduct an execution, which he refused to accept. Pouria would tell police he was also asked to kill LC and was beaten up when he said he couldn’t do it.

Senior BFL lieutenants urged patience whenever Qaumi sounded them out about what should be done. Homicide detectives were already looking at LC over a 2012 shooting, they said: the death of a BFL Bankstown member known as Yehya Amood. They told Qaumi that if he just waited LC’s gang would fall apart naturally, once he was arrested.

But by late October 2013 rumours began making their way through the underworld that LC had his own plans to kill Qaumi.

These were never proven, but gang members told police that it was a conversation between The Runner and Qaumi outside the Anytime Fitness gym at Parramatta on the afternoon of October 28 that lit the fuse for war.

Qaumi called over several senior gang members, including his two brothers, and told them what he'd heard.

“I was going to get LC anyway,” one of them heard him saying. “This gives me an excuse.”