Horticulture farmers at breaking point, leaving the industry

Horticulture farmers are quietly quitting the industry, fed up with years of unsustainable returns, a worsening labour crisis and now inflation. Read their stories.

A silent exodus of fruit growers is under way across Australia as farmers sell up, citing too few pickers and returns as unsustainable.

Record inflation coupled with two years of stable farmgate prices and a worsening labour crisis has pushed horticulture farmers, particularly those with permanent crops such as stone fruit, cherries, mangoes, apples and pears, to the brink.

For many, two years of losses during Covid – when foreign workers returned home and lucrative overseas markets became out of reach – and record inflation since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, has sealed the deal.

Others, however, have vowed to see out the next few years, pinning their hopes on open international borders, export markets opening up, domestic retailers heeding calls to significantly increase wholesale prices and an agriculture specific work visa.

Lake Boga stone fruit farmer of 53 years Ian McAlister is among those calling it quits, having had to scale back production over the past three years because he couldn’t find enough workers to pick his crop.

“If I do another year it will be 70 years on the farm. I’m not doing one more,” he said. “I’ve halved my volume in the last three years. Unless I’m guaranteed a workforce or can see the light at the end of the tunnel … we cannot keep producing fruit below the cost of production, and we’ve been doing it for two years.

“With the extra input costs and the rising costs of labour, the wholesale price of fruit needs to double to make money out of it.”

“All our inputs, everything it takes to grow something, are up at least 50 per cent. When you’re a price taker like we are, we’ve been absorbing cost increases for 10 years. The bubble has burst, we can’t do it any more.”

Chairman of the Summerfruit Export Development Association and a significant supplier of stone fruit to Australia’s major supermarkets, Mr McAlister said eight farmers around Lake Boga, in northwest Victoria, had left the industry last year alone, and he knew of at least another 20 considering the same fate.

“In 1970, when I was still going to school on the bus, there were 292 farmers here. Now there’s about a dozen real ones and the rest are only hobby farmers.

He said most who left went with little fuss. “Farmers are very proud people. You feel like you’ve failed.”

Tom Eastlake, chief executive of Cherries Australia until Sunday when he stepped down and began the process of winding up his family’s cherry business — which grew almost entirely for Asian export markets — has also called time on the industry.

Mr Eastlake, who produced about 500 tonnes of premium cherries at Young in NSW, said it was the uncertainty of the return of airfreight, a diminishing pool of labour and constraints within the domestic market that led him to leave the industry.

“Freight won’t improve, and for a small-to-medium producer like me who doesn’t have supermarket contracts, the squeeze has gotten too much,” he said.

Mr Eastlake said prior to Covid, Australian cherries occupied a market position overseas that was beyond reproach. So when Covid struck and access to airfreight was lost overnight, many overseas buyers wrongly assumed there was a problem with quality. He worried this would hurt Australian cherry exports in years to come, and he wasn’t the only grower concerned about the future.

He said the region has lost seven cherry orchards in the last two years.

“Two were fourth generation orchards that have gone now, which is very, very sad … I don’t have generations of asset wealth behind me, we have a large amount of debt, so we’re taking the conservative approach to live and fight another day rather than live through another few years of uncertainty. I’m not willing to take that risk,” he said.

One of Australia’s largest fruit growers – who did not want to be named – said the nation was in the throes of a “mass exodus” of fruit farmers.

“There’s a heap of people exiting,” he said. “Wages are high, prices are low, everyone is trying to sell to corporates, to hobby farmers.”

Victorian Farmers Federation president Emma Germano predicted this would be a critical moment in Australia’s farming history.

“When we look back in five years, ‘that was the moment when we realised there were 200,000 farmers and it turned into 100,000 farmers’,” she said. “And what are the unintended consequences of that, what does it do to regional communities?”

National Farmers’ Federation chief executive Tony Mahar said the industry desperately needed an Agriculture Visa to alleviate the nation’s shortage of farm workers.

“It is a crisis, there’s no doubt about it,” he said. “The labour crisis is at a tipping point and has been for sometime, so I wouldn’t be surprised if that’s the case, that there are people saying ‘I’m done’.”

Federal Agriculture Minister David Littleproud promised, if re-elected he would sign-up more countries to the Coalition’s Ag Visa and “continue to hold supermarkets to account to get a fair price for our farmers”.

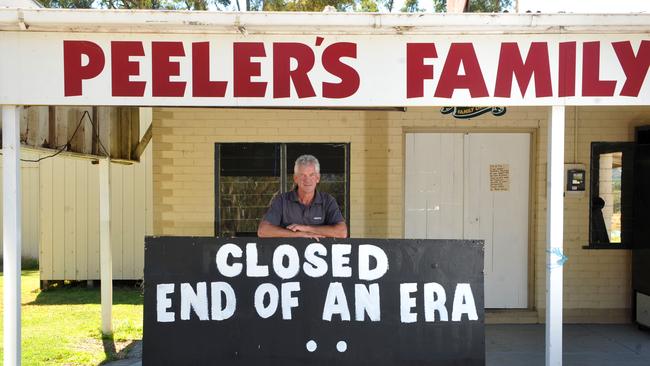

Fifth-generation former apple grower Trevor Peeler now manages the Harcourt Cooperative Cool Stores, having picked his last crop 10 years ago in Victoria’s once thriving apple growing region.

A growing workload and falling profits were what led him to wind up the farm a decade ago. He said similar concerns were playing on farmers’ minds after two “really tough years”.

“There will be a lot of decisions made following this harvest,” Mr Peeler said. Two big crops were also blamed for supermarkets buying up cheaply. “With everything going up, fertiliser, fuel and the unknowns about labour, it’s going to be a real decision making year. I know of some who lost up to $100,000 last year, so they’ll be very concerned.”

Tresco, one of Victoria’s prime fruit growing regions between Swan Hill and Kerang, has seen its population of farms run down from about 80 around 30 years ago to less than 10.

One farmer who cut his losses and sold his family’s 15ha Wood Wood stone fruit farm in December is Aldo Mase.

Given his sales were mostly to China, he decided to plant pumpkins “as a backup crop” last year. But he was unable to find enough workers to pick the vegetables so picked 150 tonne on his own.

“I’m wearing myself down, I don't have the strength to keep going,” the 57-year-old said. “In the end we were just making ends meet. I said to my wife, ‘What’s the point?’ I might as well work for someone else without the headache and be in the same situation.”

Mr McAlister said he worried that Australians were blissfully unaware they were losing their fresh produce farmers to cutthroat supermarket prices and a lack of people willing to pick the fruit, and the consequence would be cheap, imported fruit filling the void.

“If Australians want to eat homegrown food, they better start lobbying the government to give us the workers to do it, because we’ve had a gutful,” he said. “We’re going to lose the ability to produce our own food.”