Inflation hike: Are basic food items to blame for cost-of-living pressures?

Are Australian consumers unfairly blaming food for the rising cost of living? Many other expenses appear to be outpacing the staples.

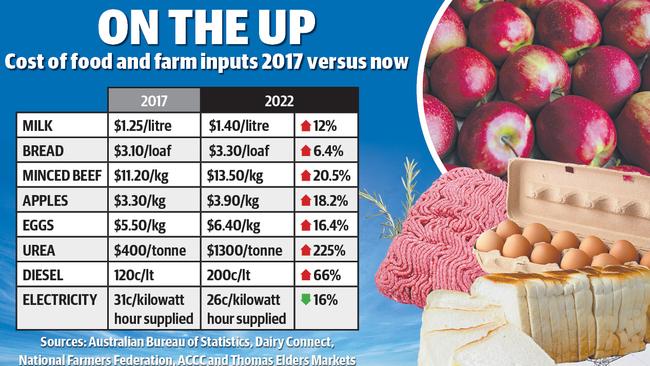

Australians are paying more for supermarket staples such as minced beef, milk and bread, than they were just five years ago.

But beyond the supermarket shelves, the cost of living expenses since 2017 have risen in goods and services that are receiving less attention from the general public — and hitting the hip pockets of farmers.

It comes as the latest quarterly Consumer Price Index data shows food inflation has lifted significantly in the first three months of this year.

The data, supplied by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, also shows food prices have recorded the highest year-on-year rise in more than a decade.

Prior to this year, most food costs have risen by less than 20 per cent over the course of five years — about 4 per cent per year — while fertilisers and fodder have risen by 100 to 400 per cent in less than 18 months.

The cost of a litre of milk has lifted from $1.25/litre in 2017 to $1.40/litre.

A loaf of bread, which used to cost shoppers about $3.10 in 2017, now costs about $3.30 on average, while minced beef mince has lifted almost 21 per cent, from $11.20/kg five years ago to $13.50/kg today.

Other expenses for regional Australians, in particular farming inputs such as diesel and fertiliser, have soared in the past five years, with diesel lifting 66 per cent since 2017 to $2/litre, and urea up a staggering 225 per cent to $1300/tonne.

Electricity prices, meanwhile, have remained relatively stable in recent years, with prices softening by 16 per cent on average.

The Consumer Index report also forecast consumers should brace for more a bigger spend at the checkout in the coming months, with transport costs, supply chain disruptions, and increased input costs begin to flush through the supply chain.

Food prices in the first three months of 2022 were up 4.3 per cent year-on-year, and almost 3 per cent on the previous quarter.

Horticulture was a major contributor to the food inflation recorded, with vegetable prices lifting 6.6 per cent and fruit almost 5 per cent year-on-year.

Queensland University of Technology professor Gary Mortimer said despite food costs generally inflating at a much slower rate than other goods and services, the frequency of grocery shopping gave a different impression.

“Some of us shop three or four times a week, some once a week or close to it.

“The frequency of purchasing food means we notice price rises almost as soon as they happen,” the consumer behaviour expert said.

“And it’s not just one item we usually purchase when we are in the supermarket, it’s dozens of individual shopping decisions.

“So when the price of everyday items rise, we then hesitate over more discretionary spending – the treat for yourself or the kids.

“When you’re paying health insurance or house insurance or other services, it’s done in a single transaction and even when there’s a steep price rise, often the customer just accepts it as part of the cost of living. So groceries are viewed in a different light.”

Professor Mortimer said the recent rise and fall of petrol prices was a good example of how consumer behaviour can vary between different purchases.

“The price of petrol is literally up in lights; it has a big impact on consumer sentiment,” he said.

“Like many groceries, we have a fairly good idea of the price at any given time whereas those one-off purchases – like insurance, or timber – we monitor as consumers far less frequently.”

Inflationary concerns come at a time when primary producers are paying more for inputs – such as diesel and fertiliser – without seeing an extra cent for their efforts despite grocery prices rising.

The National Farmers’ Federation has called on both major parties this election to commit to competition law reform, which would level the playing field for farmers.

NFF chief executive Tony Maher said many farmers continued to “be ripped off, held to ransom by the might and power of the food supply chain”, with little to no protections from Australia’s competition law.

“Australians expect farmers to receive their fair share for the food they produce. But while prices are on the up, farmers remain price takers, at the mercy of the formidable bargaining position of processors and retailers,” Mr Maher said.

The NFF has called for the establishment of the Perishable Agricultural Goods Advocate to undertake compliance and enforcement activities on behalf of the most vulnerable in the food supply chain this election.