This time last year, esteemed melanoma researcher and fitness enthusiast Richard Scolyer was cycling across Queensland and NSW as part of cancer fundraising event Tour de Cure.

Now, Professor Scolyer, who’s also the 2024 joint Australian of the Year, is in Tasmania for the same event, and is currently in the middle of riding 150km each day for three days, as more than 180 riders and support crew make their way from Hobart to Swansea, then to Launceston and Devonport. They will then travel on the Spirit of Tasmania and continue their ride to Adelaide to end their fundraising journey on March 23, in an attempt to raise $2m for cancer research.

Born and raised in Tasmania, Sydney-based Scolyer is excited to be riding the Tassie leg of the tour to enjoy some of the beautiful scenery he remembers from his childhood, and to again be participating in Tour de Cure. But there’s one major difference this year.

Last year, Scolyer participated in Tour de Cure as co-medical director of Melanoma Institute Australia, a non-profit organisation at the forefront of global advances in melanoma research and treatment, which is dedicated to preventing and curing the most deadly form of skin cancer.

This year, the 57-year-old pathologist still holds that title – but he’s also participating as someone who is battling brain cancer, after being diagnosed with glioblastoma – an aggressive and incurable form of cancer – in May last year.

Scolyer had been seemingly fit and healthy until then – with the keen triathlete having competed in a world championship aquathlon only weeks earlier. But then he travelled to Poland, to present a lecture at a medical conference, followed by some sightseeing with his wife Katie, also a pathologist, who accompanied him on the trip.

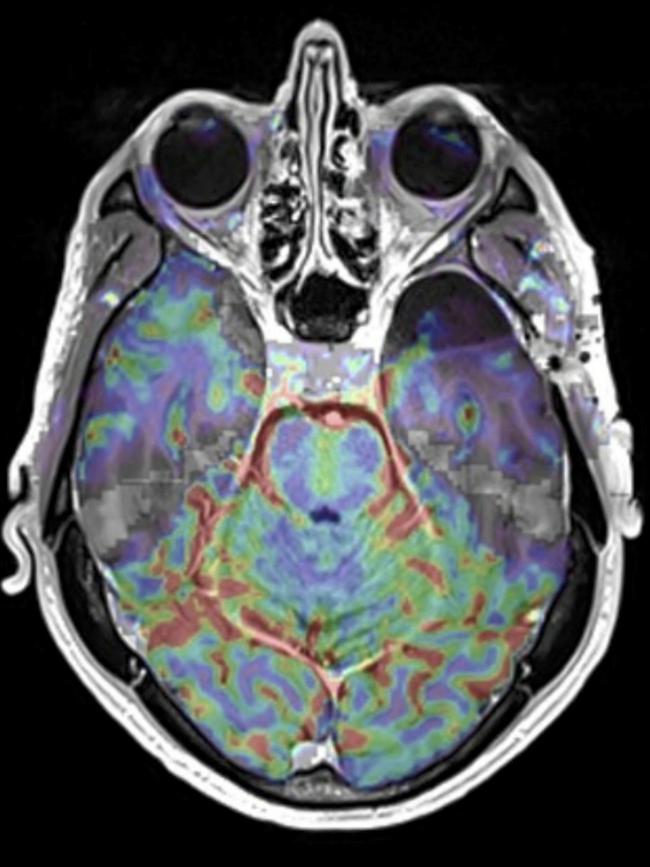

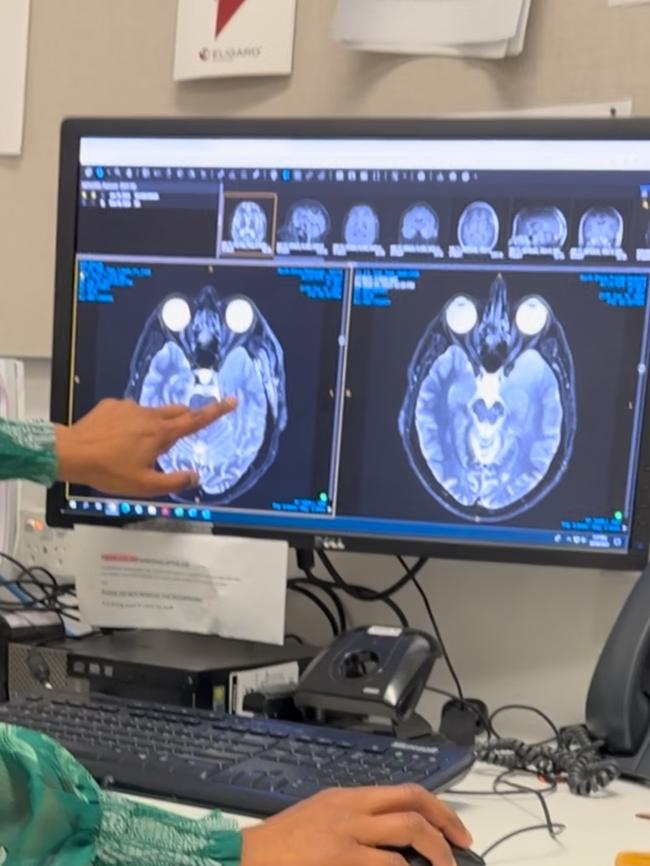

The next day Scolyer woke up “not feeling right”. He suffered a seizure and was rushed to hospital, where an MRI scan detected a lesion on his brain.

A biopsy confirmed it was glioblastoma, a cancer in which life expectancy is measured in months, rather than years.

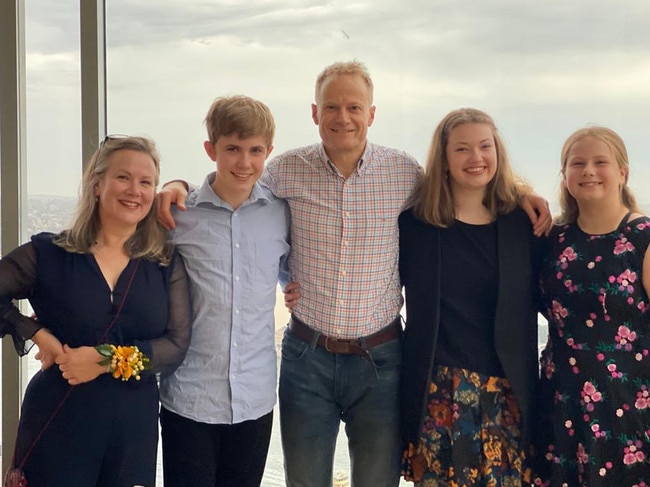

It was devastating news for the father of three teenagers, who is considered one of the world’s leading melanoma specialists and has spent his medical career helping to make life better for others with cancer.

“Whatever way you look at it, it was a total shock,’’ Scolyer says of his diagnosis.

“I have such a wonderful life doing such wonderful things.

“I’ve got my wife Katie and three beautiful children.

“I’ve got the enjoyment of my work and the incredible discoveries we’ve made. And there’s also my enjoyment in various pastimes and activities.

“I was totally shocked. To have your life turned on its head, and particularly to be diagnosed with an incurable type of brain cancer for which treatment hasn’t changed in 18 years, I was devastated. And to be honest, I still am, that this has happened to me.

“To be facing a death sentence, I’m not ready for this, I love my life … I don’t want to die yet.’’

Scolyer had a choice to make – he could sit back and prepare for the worst, or he could give himself a fighting chance by agreeing to act as patient zero in a revolutionary and risky new treatment derived from his own work in treating melanoma.

The world-leading immunotherapy treatment, which has drastically improved survival rates in melanoma patients, has not previously been used to treat brain cancer, but Scolyer and his team are hopeful it may save his life.

The treatment essentially identifies brain cancer cells and instructs the body to target them, while leaving normal brain cells alone.

Scolyer says after learning of his cancer diagnosis, his friend and colleague Georgina Long – also an oncologist and co-medical director of Melanoma Institute Australia – approached him and suggested they take every bit of medical knowledge from their extensive careers in melanoma research and treatment and throw it at Scolyer’s cancer.

“It took me a millisecond to say ‘let’s go for it, let’s give it a crack, let’s see if we can transform this cancer like we’ve done in melanoma’,’’ he says.

It was not without risk – the treatment could have caused his life to end more quickly, or had devastating side effects and caused permanent disability. But with standard treatment, the average life expectancy with his type of his brain cancer was about 12-14 months – radiation and chemotherapy could help prolong his life but wouldn’t provide a cure – so Scolyer decided to “do something that would give me a fighting chance against this tumour”.

He underwent immunotherapy treatment, followed by surgery, supported by a team of world-leading experts, in an experimental world-first for brain cancer.

Scolyer has been documenting every step of his journey, both professionally and on social media for the wider community to see. And experts from across the globe are watching with great interest – if the treatment is successful it could revolutionise cancer treatment globally.

Scolyer says the problem with brain cancer is that it’s not possible to remove all of it, as it has tiny tentacles that extend throughout the brain.

To cut out all of these tentacles would have a devastating impact on a patient’s brain function, assuming that patient even survived the surgery.

So having immunotherapy first, which trains the immune system to recognise tumour cells and kill the cancer, was his best chance of success before then undergoing surgery.

“The honest truth is, it is risk taking,’’ says Scolyer, who lobbied hard to be allowed to access the treatment for brain cancer.

“It took a lot of work to get people on-board to support this. There’s the risk you could die much sooner, or otherwise have permanent side effects that could ruin the rest of your life, even if you live a long time.

“But I feel like I’ve got this incredible opportunity to make a difference, even if it makes no difference to my outcome. Undoubtedly the data created out of my brain tumour is making a difference already and I’m very proud of that. Many people go down the path I could go down (having cancer) … as someone who works in the field this is my opportunity to make a difference. I have my fingers crossed we can transform this disease, just like we have for melanoma.’’

And so far, the results are promising. With traditional treatment options for this type of brain cancer, patients would typically see a recurrence of their cancer within six months. Scolyer is now about to hit the 10-month mark, with his next MRI scheduled for Monday – and so far regular scans show no signs of his cancer returning.

He also has no symptoms that suggest his cancer has returned. He’s still going to work each day, he’s still enjoying being physically active, and he’s making the most of the extra time he gets to spend with family and friends.

Of course he’s only one patient, so even if the treatment does work, there’s no guarantee it would work for everyone.

But a successful outcome for Scolyer and positive data generated from his journey could help the treatment reach the clinical trial stage, bringing it a step closer to being accessed by the wider population. He and Long have presented the data publicly and Scolyer says it has “blown open the field” with experts “so intrigued and excited by what our team has generated on brain tumours”. He is also currently writing up the data in preparation for submission to the world’s top medical journal.

“The data generated provides some hope this is a field worth pursuing,’’ Scolyer explains.

“It has been shared with many experts around the world who are incredibly excited about it. I’m certainly living with hope that this treatment will make a difference … I don’t know how long I’ve got left to live. I feel lucky, to be honest, even now – I haven’t had to go into hospital for any recurrence and if this treatment pans out and works, hopefully it will save lives. It must be part of my personality, I like to contribute to things and try and make a difference.’’

And he credits his upbringing in Tasmania for fostering this desire to help others.

“I love Tasmania, I lived there for 25 years,’’ enthuses Scolyer, who grew up in the Launceston suburb of Riverside.

He attended Riverside Primary School and Riverside High School – where he was head prefect – before completing years 11 and 12 at Launceston Community College.

He moved to Hobart to start university in 1985, and stayed for seven years – including the six years of his medical degree and his first year as a doctor working at the Royal Hobart Hospital.

“I always thought I’d come back (to live),’’ Scolyer says of Tasmania.

“I love it so much. But opportunities came about that took me elsewhere. But it’s still somewhere very, very close to my heart.’’

Part of that fondness comes from the fact his mum, Jenny, and dad, Maurice, still live in the state, and Scolyer talks enthusiastically about the family adventures he and his older brother Mark enjoyed with their parents in the great outdoors when they were children.

“I’ve got such great memories growing up in Tassie,’’ Scolyer says.

“I remember when I was a kid – my brother and I – my parents would take us camping at Ulverstone each year in the summer holidays.’’

They spent their leisurely days swimming at the beach. Scolyer’s parents hailed from large families so there were plenty of aunties and uncles and no shortage of cousins to kick a footy or play cricket with, or ride bikes with.

“It was just a magic period, I have great memories of that,’’ Scolyer says.

The family also did a lot of bushwalking and Scolyer has fond memories of hiking at Cradle Mountain and Dove Lake, which he describes as “one of many, many special national parks and beautiful places in Tasmania’’.

He actually returned to Tasmania late last year to visit family and friends and took the opportunity to immerse himself in some of the island state’s natural beauty.

“We walked down to Cape Pillar, which has incredible views of Tasman Island, and we just happened to be there when three leading boats for line honours in the Sydney to Hobart Yacht race came around Tasman Island and were racing home,’’ Scolyer recalls.

“Before I got burdened with this incurable brain cancer, I’d come back (to Tasmania) at least six times a year, sometimes more.’’

He’s proud of the fact his children, Emily, 19, Matthew, 18, and Lucy, 16, have a strong relationship with their Tasmanian grandparents, despite living in Sydney. He says his kids “are passionate about Tasmania, like their dad is’’.

Scolyer’s father now lives on a property at Legana, while his mum is living in a nursing home in Riverside, due to mobility issues.

His mum was plagued by health struggles earlier in her life and Scolyer says this ultimately led him to follow a career in medicine.

His mum suffered three strokes before Scolyer had even started school and his dad took her to Melbourne for about six months for intensive rehabilitation, leaving Scolyer and his brother in Tasmania in the care of other family members.

“It certainly changed my life,’’ Scolyer recalls.

“I still wasn’t at school at that stage and I went and stayed on a farm with my uncle and aunty. Mum stopped being able to talk and couldn’t move one side of her body properly.

“She went over to Melbourne for a period and Dad went with her to support her as she was given intensive rehabilitation to try and get back some of her function.’’

Richard was just three and his brother was five.

“It was a tough journey,’’ Scolyer says of what his mum went through.

“Seeing what happened to my Mum did have a big impact on me, it certainly impacted my passion for doing medicine. I was inspired by that. I wanted to make a difference, to help people, to try and make life better for people.’’

Two of his uncles who lived interstate were doctors, and a friend’s dad, who lived nearby, was also a doctor, which Scolyer believes had an impact on his decision to pursue a medical career.

“I decided in year 10 that I wanted to be a doctor,’’ he recalls.

“I don’t want to brag too much, but in year 11 I got very, very high marks in those subjects (that he needed to do to qualify for a medical degree) … I knew I was going to get into medicine.’’

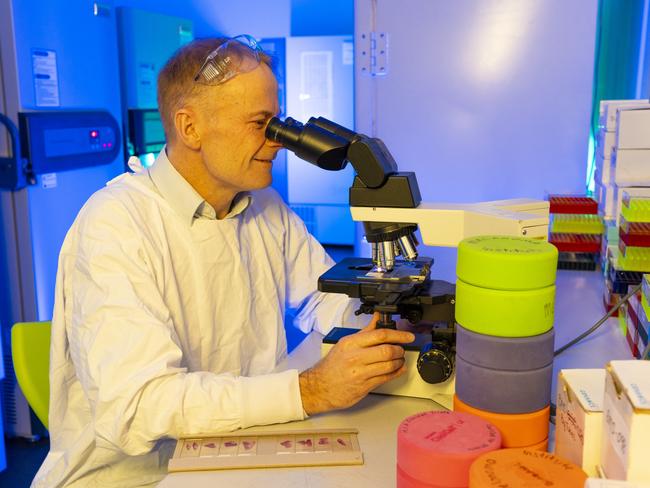

He says the “incredible” lecturers he had at the University of Tasmania, who were “inspiring and brilliant at teaching pathology” sparked his interest in the field.

“I have no doubt in my mind it’s because of the incredible teaching and mentorship and abilities of those pathologists who taught us to think ‘yeah, this is a career I’m interested in pursuing’,’’ Scolyer says.

He started pathology training in Canberra, but it was while working at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney, where the Melanoma Institute Australia was then located, that he got the opportunity to work with some of the world’s leading experts in melanoma.

And under the guidance of these renowned experts, Scolyer himself went on to become a world leader in the field, although he’s humble about his successes.

“I don’t feel comfortable bragging,’’ he says. “I’m standing on the shoulders of giants.’’

However, he admits there are “things I’ve been able to do that people hadn’t been able to do in the past’’ with huge advances in melanoma detection and treatment in recent years thanks to the hard work of the “incredible” team of “absolutely amazing” clinicians, researchers and biostatisticians he is fortunate to work with.

“I go to work every day, trying to make a difference,’’ says Scolyer, who was named 2024 Australian of the Year in January – a joint honour shared with his friend and colleague Georgina Long – which recognises the groundbreaking work of the two doctors who have saved tens of thousands of lives by revolutionising melanoma treatment.

Australia has the highest rate of melanoma in the world – more than 15,000 Australians are diagnosed each year and about 2000 patients still die of melanoma each year.

Scolyer says if a patient presented with advanced melanoma 15 years ago, they would often only survive for six to nine months, with a rare patient who might survive beyond a year or two.

“Survival rates were terrible, less than 5 per cent of people were alive five years later, and now that’s at 55 per cent,’’ Scolyer says, adding that the situation has gone from “a certain death sentence” to “hope and a cure”.

“Everyone used to die and now we’re curing about 50 per cent of patients. That’s massive progress which has never happened with another cancer before.’’

That change is due largely to the development of immunotherapy to successfully target melanoma – the same treatment that is now being used to fight Scolyer’s own cancer. Diagnostic tools have also helped improve the accuracy of diagnosing melanoma, and Scolyer is also passionate about spreading the sun safety message – and countering those who glamorise tanning on social media – to help prevent skin cancer occurring in the first place.

“We don’t want to stop people going outside,’’ Scolyer says.

“We live in one of the most incredible places anywhere in world, we all should be out there enjoying it. But we need to be smart about doing it, and we need to do it when the sun, the UV radiation, is not at its worst. It’s about going outside with a hat and sunscreen and sunglasses.’’

He also urges people to familiarise themselves with their own skin, and get any changes checked promptly, to help with Melanoma Institute Australia’s goal to reach zero deaths from melanoma in Australia.

Awareness is one of the reasons Scolyer is passionate about taking part in events like Melanoma March, and this weekend’s Tour de Cure.

The cycling event, which has been running for 18 years, aims to raise vital funds for cancer research, while also promoting conversations about cancer prevention.

Scolyer, who has participated in numerous high-level triathlon events in various parts of the world, admits his health isn’t currently at its peak. But he’s enjoying the chance to ride in his home state, along with fellow Tasmanian and champion cyclist Richie Porte.

Scolyer says exercise has always been important in his life, but particularly since his cancer diagnosis as it was “good on many levels”, supporting not only his fitness but also his mental health.

“I love exercising, I find that it’s good for mental health, and it’s a good way to catch up with mates and have fun,’’ he says.

“My life has been turned upside down. These things I enjoyed previously, I don’t know how long they will last for, things could turn around just like that. I have great hope (that the cancer treatment will work) but from time to time I do wonder how long I have left. But I don’t want to sit at home feeling sorry for myself all the time and not be contributing.’’

So using his time wisely is a major focus as he spends time with his family.

“It is a very emotional time,’’ Scolyer adds.

“I’m supported by a whole team of people and I can’t thank my family enough for what they’ve done to support me in all that I’m doing. I want to spend time with my family, with my children and my wife, to enjoy whatever time I’ve got left with them. I can’t thank them enough for their kindness and love and support as I travel on this tough journey, and as we as a family travel on this tough journey.’’•

Tour de Cure cyclists are currently travelling between Hobart and Devonport before boarding the Spirit of Tasmania and riding from Geelong to Adelaide. Expect to see cyclists travelling between Swansea and Launceston on Saturday, March 16, and from Launceston to Devonport, on Sunday March 17. For details about the fundraiser visit tourdecure.com.au

To stay updated on Richard Scolyer’s cancer journey follow @profrscolyer on Instagram.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

New series shines light on muttonbirding, wild Bass Strait island

This powerful landmark series, set against the raw beauty of Great Dog Island, is a deeply personal reckoning with heritage, fatherhood and the fragile continuity of an Indigenous tradition

Check out our picks of the best bites of the dark delights

If you haven’t been yet, there’s still time to catch Winter Feast – Tassie’s tastiest food ritual returns this Thursday. Here are a few delectable treats I highly recommend, writes Alix Davis