In the depths of grief, on the day Joe and Fiona Riewoldt’s daughter Maddie died, Joe received a phone call from a friend – who had lost a son many years earlier – offering some sage advice.

“He said: ‘You’ve gotta know, I’ve gotta tell you, that you’ll never get over it, but you’ll learn to live with it’,’’ Joe recalls.

Now, almost 10 years on from that day, when the heartbroken couple farewelled their 26-year-old daughter as she died of complications from a bone marrow failure syndrome, Aplastic Anaemia, Joe and Fiona’s grief is still devastatingly raw.

They still struggle, at times, to speak about their beloved daughter, without their voices breaking or without dissolving into tears. They miss her beaming smile, her cheeky sense of humour and simple pleasures like walking on the beach with Maddie at the family’s much-loved shack at Orford, on Tasmania’s East Coast.

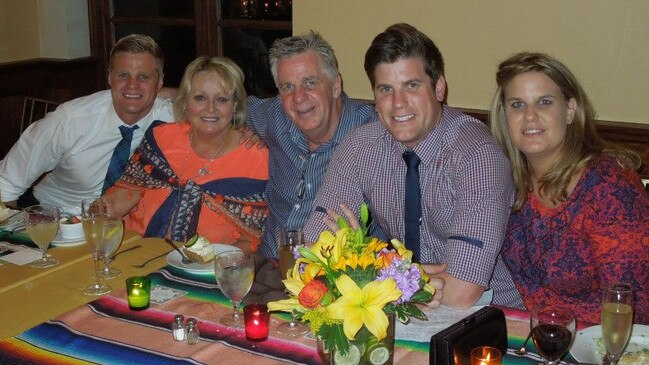

But they are also heartened by the huge amount of change they’ve been able to make in funding vital research and helping support other families through Maddie Riewoldt’s Vision, a charity the couple created in 2015 in their daughter’s honour.

They established the organisation with the help of their sons Alex, now 39, and Nick, 42, using Nick’s profile at the time as an Aussie Rules star and St Kilda captain to garner support and honour Maddie’s legacy. Joe and Fiona’s nephew, Richmond heavyweight Jack Riewoldt, also became involved, adding some extra star power to the charity’s profile.

Through a variety of fundraising initiatives – including charity golf and cricket matches, a range of purple Converse sneakers, a partnership with a major fruit and vegetable supplier, and the annual AFL match between Richmond and St Kilda, which has been dubbed Maddie’s Match – the organisation has so far committed $8.8m to research and funded 36 research projects, while also securing more than $22m in leveraged funding, with the aim of delivering breakthroughs in the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of bone marrow failure syndromes.

Treatment and support has improved significantly for patients and their families since the establishment of the charity, which – among other achievements – has created the first Centre of Research Excellence in Bone Marrow Biology in Australia to provide greater collaboration between medical experts across Australia. The charity has supported clinical trials, as well as the establishment of a world-first bone marrow failure biobank (containing patient samples which can be used for further research), and has employed a dedicated nurse supporting patients via a free telehealth support service.

November has also become known as Maddie’s Month, with fruit and vegetable producer Flavorite partnering with Maddie Riewoldt’s Vision to donate a portion of the proceeds from every specially-marked pack of cherry tomatoes or capsicums – sold in Coles supermarkets across Australia – throughout November.

So far the long-running partnership, which was established in 2016, has raised $800,000, and is expected to raise an additional $100,000 this year, while also increasing awareness about bone marrow failure syndromes – serious health conditions that many people have never heard of.

Every year in Australia, about 160 people will be diagnosed with a bone marrow failure syndrome, a collection of medical conditions where the body’s bone marrow stops working, or works insufficiently. That equates to one person every two to three days. And of those, most are under the age of 20, and only 50 per cent will survive. The syndromes can be acquired, meaning a previously healthy person can develop bone marrow failure, while for others the syndromes can be inherited in families where there is a history of the condition.

The Riewoldts knew nothing about Aplastic Anaemia when Maddie was diagnosed at age 21.

“It was an unbelievable shock,’’ Fiona recalls of Maddie’s diagnosis.

“She went to the doctor because she was tired, she had a sore throat and she had some bruising. I sent her to the doctor with my mum and said: ‘Just make sure she gets a blood test’. I thought she might have had glandular fever or one of those things. Then, of course, we got phone calls to say we had to go back in urgently. We just sat there, she and I, in disbelief.’’

Despite learning that something was seriously wrong with Maddie’s health, it took quite a while – and lots more tests – for a diagnosis of Aplastic Anaemia.

Joe says plenty of well-meaning friends contacted the family upon hearing that Maddie was unwell, but most didn’t understand the seriousness of her diagnosis, because so little is known in the wider community about bone marrow failure syndromes.

“They’d say: ‘Has she got cancer?’ and we’d say: ‘No’, and they’d say: ‘Oh, thank goodness’,’’ Joe recalls. “And we’d sort of say: ‘Well, it can be just as deadly as a cancer’.’’

At that time there had been limited research into the condition, and there was limited information and limited treatment options, so the couple say in many ways it felt more daunting than a cancer diagnosis might have been.

Maddie battled the condition for five years and, at her worst, she spent 227 consecutive days in the intensive care unit at the Royal Melbourne Hospital.

Watching their daughter become so ill was frightening, but Joe always expected she would recover.

“It wasn’t until the day we lost her that we thought we would – we always thought she would just come right, she was such a fighter, she’d go down and come back,’’ he explains.

“But in the end it was organ failure, her lungs and kidneys and heart just couldn’t do it any more.’’

Bone marrow is an important and complex organ, and quite literally our factory for blood cells. Healthy bone marrow works to produce new red and white blood cells and platelets every day. But in bone marrow failure syndromes the bone marrow stem cells can’t produce enough healthy red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets to meet the body’s daily requirements, which can lead to serious illness or death.

Treatments for bone marrow failure syndromes are usually aimed at counteracting the effects of low blood cell counts, with blood transfusions for low red cells or platelets, medication to encourage the bone marrow to produce blood cells, antibiotics for infections and sometimes immune suppressant therapy, or bone marrow transplants.

Maddie had 200-300 blood transfusions to keep her alive during her battle with Aplastic Anaemia and it was during her long stays in hospital that the idea of advocating for change was first raised by Maddie.

“The reason it’s called Maddie Riewoldt’s Vision is that it was her vision,’’ Joe explains.

“She said that when she got better – and we talked about it a lot in hospital because we had to focus on something – she was going to go and contact organisations and go to schools and sporting groups, wherever she could talk to a bunch of people at one time … about the importance of donating blood and blood products like platelets. She wanted to do that.’’

He says while a healthy human would typically have a platelet count of about 400 to 500, at times Maddie’s count dropped as low as four.

“It was terribly frightening,’’ Fiona recalls of watching her daughter’s health decline.

“She couldn’t live a normal life.’’

When Maddie died, Fiona and Joe were determined to fulfil their daughter’s wish to raise awareness about bone marrow failure syndromes.

“The day we lost her was the day that we said ‘we’re going to do something – we’re going to start a foundation’,’’ Joe explains.

“We didn’t know what we were going to call it but vision seemed like an obvious word as it was her vision.’’

And, they say, the idea has progressed – “big time” – beyond anything they could ever have imagined, thanks to an influx of community support.

“We felt we were obligated to do it because we had a platform – that platform being the profile of Nick, and then Jack’s profile added to this,’’ Fiona says.

Adds Joe: “We had a platform we knew we could use and we knew we could do good with it.’’

Fiona says it’s not easy in the current climate to raise money for charity, with rising costs of living and plenty of other worthy causes competing for fundraising dollars.

But Joe says the Riewoldts pride themselves on maximising the benefit of all donations and are pleased the charity has been able to transcend football, with support continuing to grow, despite Nick and Jack no longer playing.

About 80 per cent of funds raised go directly to research, while the rest of the funds cover the cost of the biobank, the Centre of Research Excellence (which is a virtual centre acting as a central contact point for medical professionals, researchers and community groups across Australia, rather than a brick and mortar establishment), and the organisation’s telehealth nurse, who Joe describes as an “absolute angel” who is essential for “helping families to know they’re not alone” and for “alleviating some of the angst” that comes with having a rare and often misunderstood condition.

“What was very close to my heart was how isolating the whole experience was, not just for Maddie – it was horrendous for her – but for the whole family, we felt so alone,’’ Fiona says.

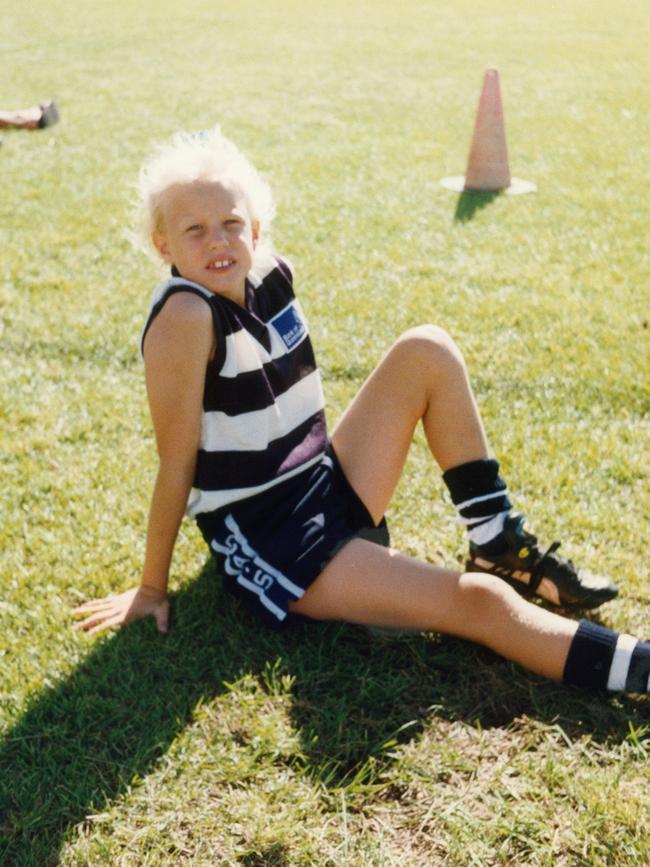

Joe says his “mad keen, talented sportswoman” daughter would be “blown away” by the difference the organisation has been able to make so far when it comes to research, advocacy and supporting families.

“Obviously it has gone way above what she ever envisaged it might be,’’ he says.

Fiona believes Maddie would be “immensely proud” of what has been achieved in her honour, but would also be bemused by all the fuss.

“Maddie was a very funny girl, she had a great sense of humour and she would just raise her eyebrows and go: ‘Really?’,’’ Fiona says of the foundation’s success.

Meeting other families who are going through a similar journey to theirs is heartening but also heart-wrenching.

“You get to know some of the families and the young children,’’ Joe says.

“You get really attached and see how brave they are and then they die and it’s just horrendous.’’

Fiona says it can also be hard sharing their story of loss with other families who are hopeful that their own children will survive.

“It can be very hard making that connection when people know that Maddie didn’t survive,’’ Fiona admits.

“It’s difficult – I wonder would they rather I didn’t talk to them, because it brings the reality to the forefront that this is what can happen.’’

But ultimately knowing they are helping others does help ease some of their heartache, and provides what Joe describes as a “positive outlet” for their grief.

“You have no choice, you have to live with it,’’ Fiona says of the reality of losing a child.

“I grieve this every day of my life, I miss her every minute of every day. I still have really bad days and then I have better days. It’s cathartic in some respects, I suppose, that we are hopefully helping other people, when we couldn’t help our own child … day in, day out, we were watching her suffer. We have to take some sort of solace from the fact that maybe we’re going to be able to alleviate some of that for other people.’’

Joe says milestone events – like birthdays – are tough, but simply missing out on day-to-day life with Maddie is what hurts most.

The 10th anniversary of Maddie’s death is approaching – February will mark a decade since they said goodbye to their daughter.

“Obviously days like birthdays and Christmas and Father’s Day (are hard) – I don’t get chocolates on Father’s Day any more, that was a thing between her and I,’’ Joe says.

“Lots of things that we used to do together, you just miss it.’’

But Fiona and Joe, who are based in Melbourne, find comfort in retreating regularly to Tasmania where they feel closest to Maddie.

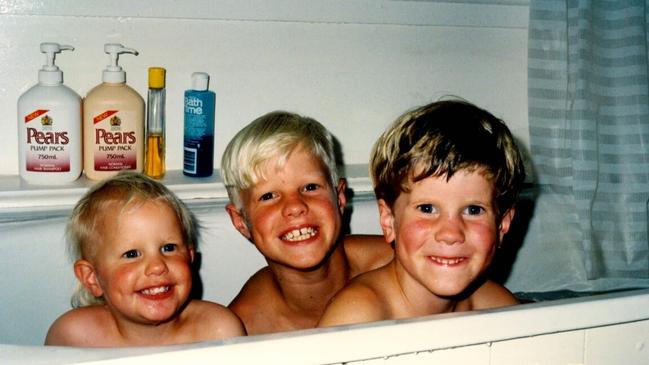

Both Fiona, 67, and Joe, 70, grew up in Tasmania – Joe was a talented footballer with Clarence Football Club – and all three of the couple’s children were born at Calvary Hospital.

Joe worked as a sales manager for Tas TV, but is best known for the years he spent as licensee of Shipwrights Arms Hotel, at Battery Point.

The family moved to Queensland’s Gold Coast in the early 1990s, when eldest son Nick was nine, but have always remained Tasmanians at heart, returning regularly to the East Coast, where Fiona’s extended family has been holidaying since the 1920s.

Their five grandchildren are the seventh generation of the family to holiday at Orford, and Fiona and Joe are increasingly spending time here now that they’ve retired. They spent five months in Tasmania from November last year to April. And Joe most recently visited Orford earlier this month.

“I just love it,’’ Fiona enthuses of the family shack at Orford.

“It’s my happy place. And Maddie called it her happy place too.’’

Joe and Fiona say during many of those tough days in hospital the conversation would revert to talking about Maddie’s happy place, and she longed to escape the hospital for a walk on Orford’s sandy shores.

Maddie’s funeral was held in Hobart and her ashes were scattered at Orford’s Millington Beach, a place named after her great grandfather.

“We took Maddie back to her happy place,’’ Fiona says.

“Which I love. My biggest joy, I suppose, is just walking on that beach – come snow, rain, hail … there’s something special about the Tassie coast and the Tassie beaches, they’re just beautiful.’’

The couple cared for Maddie’s precious dog, Oscar, after she died. And while they were devastated when Oscar died last year, they had the dog cremated and spread his ashes at the same beach so he would always be with Maddie.

“Tassie will always be home, and we come back as often as we can,’’ Joe says.

One of the patients Maddie Riewoldt’s Vision supports is Tasmania’s Matthew Dunn.

The 15-year-old from Burnie had open heart surgery when he was just three months old and was also diagnosed with bone marrow failure syndrome Fanconi Anaemia around that time.

Matty lives with a number of physical disabilities – he has club hands, he has only one kidney, he has problems with his vision and hearing – and he’s also monitored closely by haematologists due to his high genetic chance of getting head, neck and throat cancers.

He is cared for by his grandmother Cheryll Opperman, who says the support of Maddie Riewoldt’s Vision has been amazing.

When Matty was first diagnosed with Fanconi Anaemia, Cheryll says the outlook was bleak.

Being such a rare condition, there was not a lot of information available in those early days, but now having a dedicated organisation funding research and support had made a world of difference.

She speaks regularly with telehealth nurse Mei-Ling Yeh, who she describes as an “amazing” wealth of knowledge and support. And she is heartened by clinical trials and research which are improving treatment and quality of life.

Most of Matty’s medical needs can be met at Hobart’s Royal Hobart Hospital but visits to St Vincent’s Hospital in Melbourne – which has a department dedicated to Fanconi Anaemia research – are sometimes required.

“Research is bounding forward,’’ Cheryll says.

“For us, we know they can never cure Matty’s Fanconi Anaemia. But we also know that they’re coming up with new treatment protocols, and – for us – that’s huge if he goes into bone marrow failure.’’

Two out of every three patients with Fanconi Anaemia will go into bone marrow failure, but Cheryll hopes Matty will continue to be the one in three that doesn’t. Matty has a shorter than average life expectancy, but Cheryll says there are some with his condition who have lived to the age of 40.

The two have a strong bond, and Cheryll says despite the struggles he faces, Matty is “super chill and relaxed” and “takes things in his stride”.

“We have a beautiful connection, Matty and I,’’ the 61-year-old says proudly.

“We have a beautiful time together, we enjoy each other’s company … he’s a cool kid. He’s very resilient and tough. And he’s got a fantastic sense of humour, he finds humour in everything. He’s very fun to hang out with … he sees the funny side of life.’’

However, she admits life can be lonely for Matty, who also has autism.

He has been at a support school but will next year begin grade 10 at Marist Regional College, where he will have more access to creative subjects he loves, like art, writing and drama.

Matty is passionate about birds – Cheryll says he “can tell you anything you’d ever need to know” about his pet cockatiel and budgie – he also loves Minecraft and Roblox, he loves to travel and the keen cook has mastered the art of making dumplings.

Matty, who in 2021 did the coin toss at the annual AFL Maddie’s Match between St Kilda and Richmond, refers to Cheryll as “Honey” and calls her his “hero”.

November is Maddie’s Month, with Flavorite donating 15 cents from every specially-marked pack of cherry tomatoes and capsicums sold in Coles supermarkets across Australia to Maddie Riewoldt’s Vision to fund research, advocacy and patient support. There’s merchandise online and donations can also be made directly at mrv.org.au

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Romance boom: Tassie author pens 100th book

Tasmania’s Ris Wilkinson became an author at 44 with romance juggernaut Mills & Boon. At 66, she’s penning her 100th book as Melanie Milburne – as writers converge on Hobart for a national event.

Coal River vineyard dishes up quiet culinary bliss

With a striking cellar door, smart seasonal menu and standout wines this vineyard is a must-stop in the Coal River Valley. Come for the views, stay for the food and a second glass of pinot ...