When Sarah Okenyo started making a documentary about the Derwent Valley Concert Band 10 years ago, she had no idea how the story was going to end.

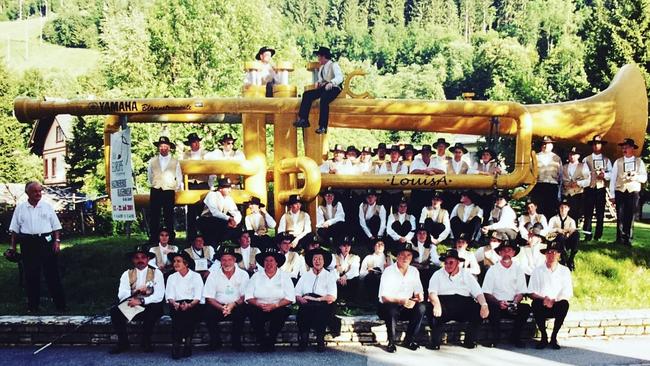

She thought maybe her focus could be around the international success of the band, and the elation at winning the European Open Band Championships in Germany in 2015.

She never imagined that her father Layton Hodgetts – the band’s much-loved founder and conductor – would fall ill, and eventually succumb to lung cancer in November 2020.

And as heartbreaking as the past three years have been for Okenyo – and the wider concert band community as they come to terms with the loss of such a talented and respected leader and friend – she says the documentary, titled A Town Without Music, has also provided a sense of joy and healing.

The 40-year-old is working to finish the project, as a moving tribute honouring the band, and her father’s legacy.

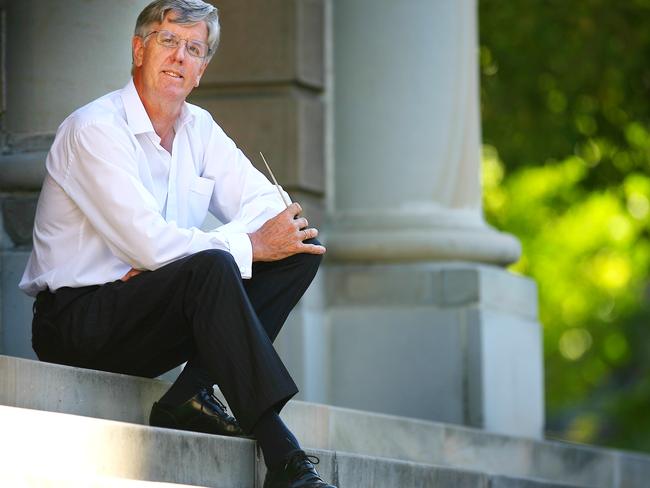

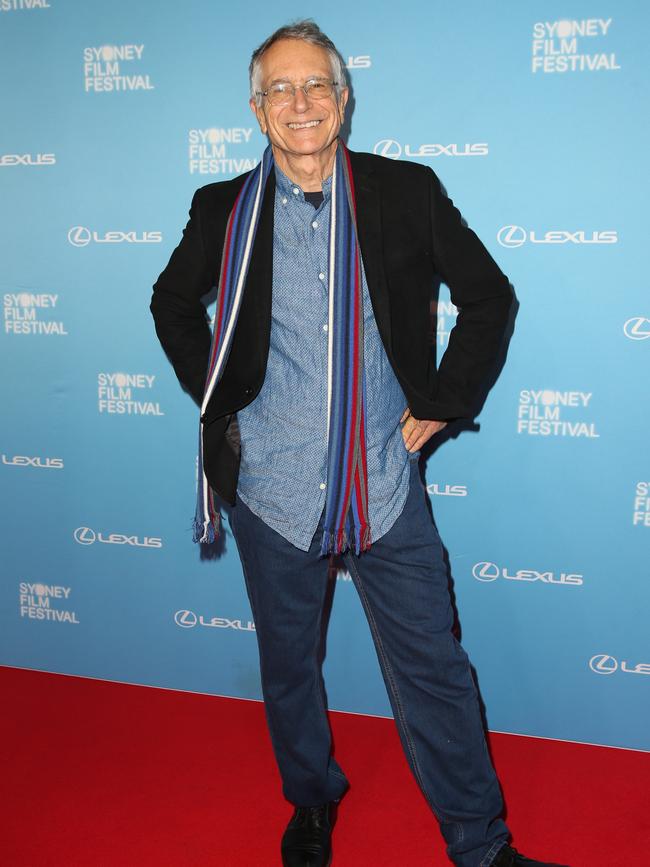

She has what she says is “one of the best producers in the country” – internationally-acclaimed documentary filmmaker Tom Zubrycki – on board to help complete the project, and they hope to showcase the documentary on the world stage.

There are plans for the doco to tour film festivals, to screen at cinemas around Australia and hopefully be picked up by a streaming service like Stan or Netflix.

They are lofty goals but Okenyo, who has studied film and documentary making in Australia and overseas, is confident her heartwarming film will capture the attention of audiences.

But first she needs the support of the wider community to help raise funds to complete the project, which is $44,000 short of its fundraising target.

Okenyo has secured $15,000 in funding from Screen Tasmania, some of which has already been used to bring Zubrycki to Tasmania and to hire crew to film additional footage for the documentary. She has also put together a short 10-minute teaser to promote the project.

Okenyo is also being supported by Documentary Australia, which is managing a tax-deductible, crowd-funding campaign for the project, which has already raised almost $16,000.

“It’s a really great start,” Okenyo says of the fundraising.

“I want to take it to film festivals, and we would love to put it into cinemas like the State in cities around the country. And get it onto streaming services, like Stan or Netflix … that’s the goal. We’re wanting to take it as far as we can on the world stage.’’

A Town Without Music will be Okenyo’s first feature-length film, and it is a heartwarming story about the power of music in a small community.

Hodgetts spent his career working as a music teacher, at schools including New Norfolk High and Fairview Primary, and started the community band due to a lack of musical opportunity for his students.

Many students enjoyed playing music in bands at school. But once they left school, they often didn’t have their own instruments, or any outlet to be able to continue playing music.

The band was established in 1993 and went on to achieve unimaginable international success with 10 overseas tours, winning the European Open Band Championship twice, and even performing at the Danish royal wedding when Tasmania’s Mary Donaldson married Denmark’s Crown Prince Frederik in 2004.

There were plenty of setbacks along the way – Okenyo says a small minority of locals didn’t support Hodgetts’ musical vision for the regional town, and some considered him a tall poppy who needed to be cut down.

Hodgetts was attacked physically and verbally, but stood firm in his mission to share music with the masses.

Okenyo says when her non-smoking dad was diagnosed with lung cancer, band members were a huge support, even performing a “living wake” in the garden of their family home, as a very unwell Hodgetts watched on from the comfort of his veranda, where he gave one final speech to his musical comrades.

“Dad loved people as much as anything,’’ Okenyo says.

“He was kind of worried about having a funeral and not being there, he didn’t want to miss out. So we said, ‘don’t worry Dad, we’ll do something else’.

“Although it was sad, it was one of the best things I’ve ever been to. It was so meaningful, there were lots of laughs and fun had, even though there was this deep sadness.’’

When Hodgetts died, at the age of 77, 99 musicians marched ahead of his hearse through the streets of New Norfolk as part of his funeral procession.

Okenyo says it was this outpouring of support that inspired her to continue with the documentary. Throughout the hard times she kept her camera rolling, keen to capture the incredible sense of community she was witnessing. She really wanted to shine a spotlight on that amazing sense of community that had grown out of the band’s creation“When Dad did get sick, I was just so overwhelmed by how the band community responded,’’ Okenyo says.

“That was another thing worth sharing – I couldn’t have gotten through such a horrible shock and loss without such a great group of people.’’

Okenyo started interviewing people for her documentary in 2013.

“I love storytelling, I love film making,’’ she explains.

Born and raised in New Norfolk, Okenyo had been studying documentary making and working for the Sydney State Theatre, where she used to “watch documentary after documentary”.

And she realised the story of the Derwent Valley Concert Band, and the way the band had transformed a small community and had achieved success on the world stage, was a worthy tale to tell.

“I thought ‘ooh, I think I’ve got a story’,’’ Okenyo recalls.

Her mum, Jane Hodgetts, who is now 81, is a retired librarian and kept careful records of the band’s successes over many years.

Okenyo has spent a lot of time going through her Mum’s archives and digitising everything band related, including VHS and camcorder footage and photos.

“Because it was something I wasn't being paid for, and it was something I was doing out of passion, I just kept chipping away, bit by bit.’’ she says of her documentary making.

She kept filming over the years, not knowing exactly which direction her documentary would take or what the defining moment would be.

“I was originally thinking it was going to be the 2015 European Championships, which we won,’’ says Okenyo, who grew up playing piano and clarinet and performing in bands, including the Derwent Valley Concert Band.

“I thought that would be the end, and I was on that trip and I was filming.

“The band would always go away and try really hard, we’ve got some amazing players in our organisation. But we just love travelling together, there was not a lot of pressure on us really, so when we’d come out winning, it was such a shock to us.

“The success the band has had is just wonderful. And I thought that would be an amazing end to the film. But obviously with Dad’s illness, and more the way the band responded to his illness and his death, it just showed everything I was trying to tell in a way. I realised I don’t need to say anything, this is just showing it. A group of amazing people who are like a family.’’

Another issue Okenyo wants to draw attention to through her documentary is the overall reduction in music education across Australia.

“The state of music everywhere is really in decline,’’ Okenyo says.

“So in that way, the documentary isn't just for the town and the band, but it’s a bigger story in many ways, and I hope it will have a positive impact in that way as well.’’

She says education experts suggest 70 per cent of primary students in public schools in Australia don’t have access to music education in their classroom from a qualified music teacher. And bands are increasingly noticing that they aren’t getting young recruits from schools in the same way they used to, because there isn’t the same level of music being taught in schools any more.

Which Okenyo, who played music and sang in choirs at New Norfolk Primary School and Ogilvie High School and joined Derwent Valley Concert Band when she was 13, says is a huge tragedy.

“It is so well documented how positive music can be,’’ she says.

“My film is not scientific, but I hope it provides an example, a case study, showing the connections to community that come through music. Dad always said music shouldn’t be reserved for private lessons, it should be something that is available to everyone.’’

Okenyo grew up loving performing, and initially started out her career as an actor rather than a documentary maker.

“I was always in plays and short films and then I was in New York for a couple of years, studying acting for film,’’ she explains.

While there, she was watching a lot of productions, on Broadway and elsewhere, and realised she needed to change direction.

“I realised that actually, what I loved most, was the storytelling part,’’ she says.

“So I started to write more.’’

She came back to Australia – to Sydney – when her visa expired and started writing and putting on plays, working for the State Theatre in Sydney.

And then she met her husband – Alexander Okenyo – who was in a choir with her dad, and that brought her back to Tasmania.

“It didn’t feel like a backwards step because I’d been doing so much learning and taking things in,’’ Okenyo says.

“I was in a really good place. I also felt, being in Sydney, I had to do three jobs and had no time, just to survive. But being back here gave me the gift of time.’’

It also gave her the gift of time to spend with her dad when he became unwell.

She has many fond memories of him.

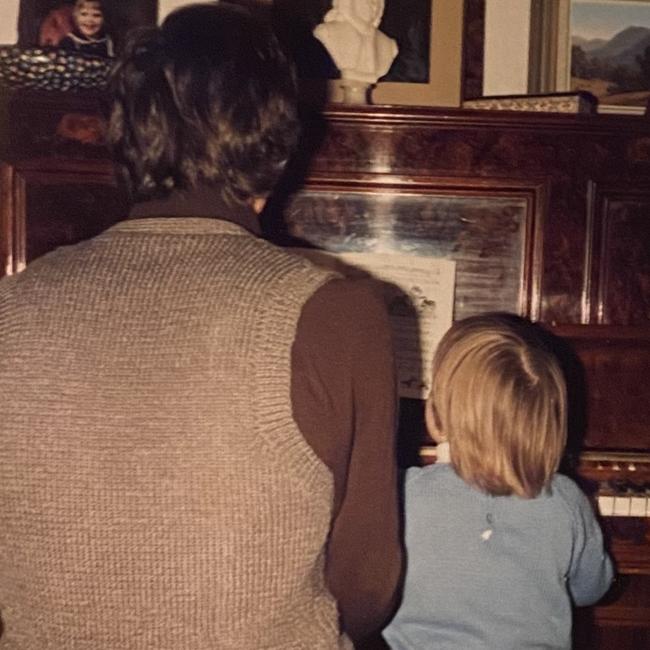

“I learnt the piano from a very young age and I was always in choirs and things like that,’’ Okenyo says.

“In terms of my dad, when I was growing up, there were always choir rehearsals happening in the house, I’d go to sleep to the sound of people laughing and singing, and things like that.

“Dad was very busy – before mobile phones he’d get on the landline and call all these people to remind them about rehearsals. And he’d travel around and pick people up from Glenora or Sandy Bay or wherever – he didn’t want people to miss out.

“He was larger than life. And I didn’t realise he wasn’t like everyone else really, until his passing in a way. Growing up, it just seemed normal. But now I have a new appreciation for everything that he did.

“Dad was one of my best friends and we were so similar in many ways – we both talk too much.

“He was a lot of fun and had a great sense of humour, and he was so accepting, and there was no judgment – he just loved everyone and it was a great influence and presence to have.’’

Okenyo has fond memories of travelling with the band. She remembers visiting China in 1999, when she was 15, and band members felt like rock stars as they performed to a packed Olympic stadium.

Hodgetts’ decision to teach the band to march – an idea many people laughed off initially – presented amazing opportunities. The band has performed in countries including Canada, Germany, Sweden, Italy and France, just to name a few.

“Dad was just such a talker and loved people, so every trip we went on led to another trip,’’ Okenyo says.

The band had been to Denmark in 2001, hosted by a Danish band organisation, so when the royal wedding was set for 2004, Hodgetts got a call for the band to again play in Denmark.

“They contacted dad from Denmark and he was shocked,’’ Okenyo recalls.

“There were kids that went on that trip that had never been on an aeroplane before. And they were at a Danish royal wedding!

“All the fundraising we had to do – these things cost a lot of money – was very special and brought the whole community together.’’

She says her dad had no idea, when he placed an ad in the local paper, wanting to start a band, that it would grow to what it is today.

“Never in his wildest dreams did he imagine the trajectory,’’ she says.

“I think that’s the thing, one of his secrets. Whenever an opportunity would come up, as crazy as it may seem, he’d say ‘yes’ and work backwards to solve all the problems.’’

“He’d say ‘What a great idea’ then, ‘oh, hang on, we have to raise $150,000’. But we always did it.’’

Okenyo doesn’t currently play in the band, having taken a break when her daughter Ivy, now 4, was born. But she was involved in organising a gala concert last month to celebrate the band’s 30th anniversary.

She’s also coordinator of a Learner Program for adults and children aged 10-plus which encourages and supports people with no musical experience to learn an instrument, learn to read music and play in an ensemble.

It’s part of a wider plan to nurture the next generation of musicians and ensure the Derwent Valley Concert Band has a strong pool of musicians for many years to come.

The Derwent Valley Concert Band is now conducted by Lyall McDermott, and Okenyo says the organisation is in safe hands.

“Of course Dad is very missed but the band keeps him alive in so many ways,’’ Okenyo says.

“For me, it’s so important to be a part of it, because we share so many common memories.’’

Okenyo says before he died, her dad was out planting trees in the garden, even though he’d never get to see them grow. But he knew he was planting them for others to enjoy, long after he was gone. And it was the same philosophy with the band.

Which is another driver for Okenyo, to ensure the longevity of the band and to complete the film, so she is creating something tangible that Hodgetts’ grandchildren – and the wider community – can remember him by.

“Ivy, my daughter, she was 18 months old when Dad died,’’ she says.

“I also have a stepdaughter, Ada, who is 15. They are both musical. So creating that legacy is really special.

“I feel like I am where I should be,’’ she adds.

“I love these people and I’m just so proud to share their story. They’re really some of the best people I’ve met and I just think what a privilege to be able to document their story as a bit of a legacy to the whole band and to Dad.’’

Okenyo hopes to raise the money she needs quickly, as her producer is hoping the project can be finished within a year. The plan is to start editing it in April next year, and have it ready to go in October, so it can hopefully be seen in 2025. •

Find out more about Sarah Okenyo’s A Town Without Music project on Facebook and Instagram or visit documentaryaustralia.com.au/project/a-town-without-music

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

New series shines light on muttonbirding, wild Bass Strait island

This powerful landmark series, set against the raw beauty of Great Dog Island, is a deeply personal reckoning with heritage, fatherhood and the fragile continuity of an Indigenous tradition

Check out our picks of the best bites of the dark delights

If you haven’t been yet, there’s still time to catch Winter Feast – Tassie’s tastiest food ritual returns this Thursday. Here are a few delectable treats I highly recommend, writes Alix Davis