Debi Marshall is privileged to be a caretaker of stories

True-crime writer Debi Marshall says it’s a privilege to gain the trust of people haunted by the deaths of their loved ones, to the point she is able to share and tell their poignant stories.

TasWeekend

Don't miss out on the headlines from TasWeekend. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Most teaching students opt to complete their practical placements working with kindergarten, primary or secondary school students.

But a young Debi Marshall decided to instead delve into the psyche of prisoners, teaching writing skills to inmates at Victoria’s Pentridge Prison.

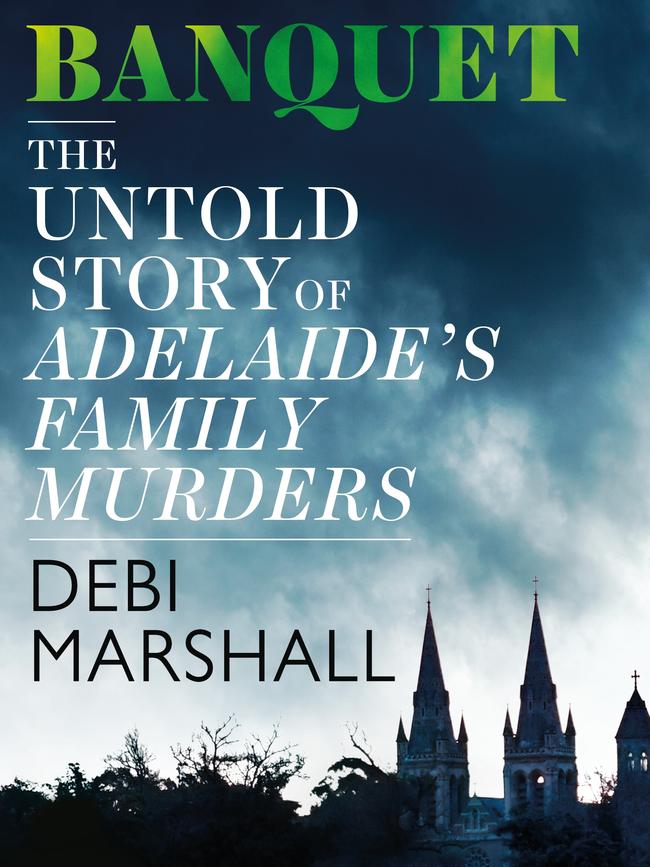

Now a best-selling author, with six of her nine books investigating Australia’s unsolved murders and serial killings, Marshall says the prison placement fuelled her long-running fascination with crime and ultimately led her to become an author. Her newest book, Banquet:

The Untold Story of Adelaide’s Family Murders, is being launched in Hobart this week.

“When I was young and stupid I didn’t know what to do with my life,’’ explains Marshall, who grew up in South Hobart but left the state in her late teens, bound for Adelaide after closing her eyes and pointing randomly at a map of Australia.

“I couldn’t get into journalism, that’s what I’d always wanted to do. So I decided to become a teacher. But as much as I loved the students in Darwin, where I taught, I quickly realised it wasn’t the career choice for me.’’

Still, that placement at Pentridge stuck with her.

“I was fascinated by their backgrounds,’’ she says of the prisoners she met during that time. “I expected they’d all be two-bit crims but then I realised some of them had uni degrees.’’

After discovering she wasn’t cut out for teaching, Marshall contacted the NT News office to ask if there were any jobs available.

“I rang the local newspaper in Darwin one morning and said ‘look, I really want to become a journalist’,’’ Marshall recalls. “The guy on the other end of the phone was a real smart arse. He said ‘And I suppose you’ve got an arts degree, and I suppose you write poetry’. So I said ‘Are you this rude to everyone who calls in?’ And I think he was a bit taken aback by my directness and he said ‘can you be in here by 4.30pm?’ ”

So at the age of 25 Marshall embarked on what was considered a “mature-age cadetship”.

She only lasted about six months at the NT News before moving on to write for other publications, but says she quickly realised she’d found her calling as a journalist. “I got into journalism and I got into feature writing and I hit my straps – I really loved it,’’ she says. “I’ve always loved chatting to people.’’

She started writing crime stories and became more and more interested in the genre as she tried to understand the inner workings of the criminals she was writing about.

“I just had this real interest in why people do what they do,’’ Marshall explains.

“Why do they take the wrong path?’’

She was approached to write biographies and once she got a taste for writing books, Marshall moved into writing true crime.

And, now aged in her 60s, Marshall says “I’ve never looked back’’.

“Unsolved serial killings are my genre,’’ she explains. “I put my investigative hat on and I have a look at the underside of what’s happening.

Is it solvable or is it not? “I’m not a police officer. But I’m certainly fascinated by reading trial transcripts and coronial inquiries. And I’m really lucky that I have a huge contact list across the country.’’

One of her early crime books, Killing for Pleasure, about the “bodies in the barrel” case on which the Snowtown film was based, was sparked by an article Marshall wrote for Marie Claire magazine.

“I came out of that knowing I had to write a book,’’ the Walkley Award-winning journalist explains.

“I just couldn’t fit it all in a feature. “I just was hooked … I knew that I’d found my niche.

“And I knew I couldn’t go back to magazines all the time – writing shorter pieces wouldn’t really satisfy me.’’

Marshall’s own personal experiences with crime and grief also shaped her journey as an author.

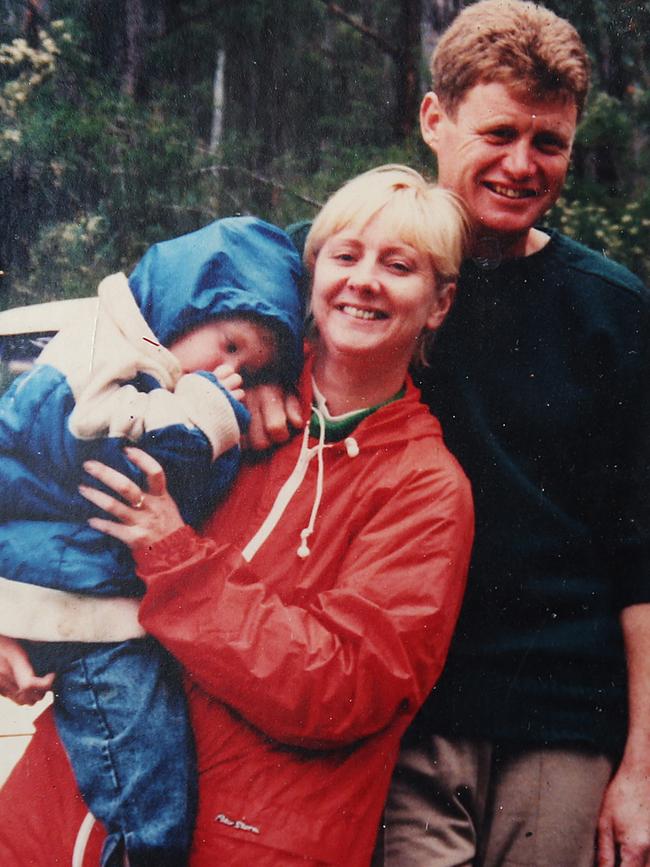

Her partner, Ron Jarvis, was murdered in 1992. A decade later, his killer, Stephen Standage, murdered another man.

Marshall says that during her pursuit of Standage, who was the last person to see Jarvis alive, he “attempted to terrorise me into silence”.

She says it wasn’t uncommon to hear the “phone jangling in the middle of the night and no one on the end of the line’’. Along with “threats to back off, or wear cement boots’’.

Jarvis’s body was found in isolated Tasmanian bushland seven months after he went missing.

“I understand the pain of waiting day in, day out, for someone you love to come home, the pain of not knowing what has happened and the agony of hearing the worst,’’ Marshall says. “I understand the relentless need for justice and the bittersweet victory of a successful prosecution.’’

As a mother, she is especially moved by the experiences of parents whose children have been murdered, like those in her latest book, which investigates the brutal and meticulously planned murders of five young men, aged 14-25, in Adelaide between 1979 and 1983.

“To lose a partner is painful, but to lose a child must be incomprehensibly so,’’ Marshall says.

After Jarvis disappeared, Marshall recalls living her own personal nightmare. “I couldn’t eat, I couldn’t sleep, I lost so much weight,’’ she says.

She doesn’t share her experience of loss with the people she interviews – she says her own grief pales into insignificance when compared to that of some of the families who have been grieving the loss of a brutally murdered child for 40 years – but her own experience does give her a greater level of empathy and understanding.

“I guess because I love what I do and I love the people I deal with – mostly – I form a bond of trust with them and vice versa that gets us through all sorts of things together,’’ Marshall says. “I listen in a way that is empathetic. And I never promise them anything.

“I suppose I carry a little bit of Ron with me all the time. We were together two years. Something like this just completely changes your life.’’

Marshall is the youngest of six children. And when she announced she was writing Killing for Pleasure – which was published in 2006 – her brother warned her that she would forever changed by the experience.

But Marshall never imagined just how big a toll writing investigative crime stories would take. And she says conducting research for her newest book, Banquet, was “often akin to playing hopscotch in an undetonated minefield”.

Marshall was moved to write Banquet after hosting a five-episode Foxtel series, Debi Marshall Investigates Frozen Lies, which aired in 2019.

She says the series, which begins with the murder of criminal lawyer Derrance Stevenson in 1979 and continues into the cases of The Family murders, revealed “a complex labyrinth of questions and possibilities’’ which Marshall wanted answers for.

A podcast of the same name followed the TV series and when Marshall put out a call for people to come forward with information relating to The Family murders she was blown away by the flood of people who contacted her, wanting to share their experiences.

The Family is the name given to a loosely connected group of individuals believed to be involved in the kidnapping and sexual abuse of a number of teenage boys and young men, as well as five murders in South Australia in the 1970s and 80s.

“I had researched the story for years but with people coming forward on the back of revelations aired in the series and podcast, I now had more contemporaneous material based on their memories,’’ Marshall says.

“I was under no illusions that this would be a tough story to write, but just how tough, I could never have imagined.’’

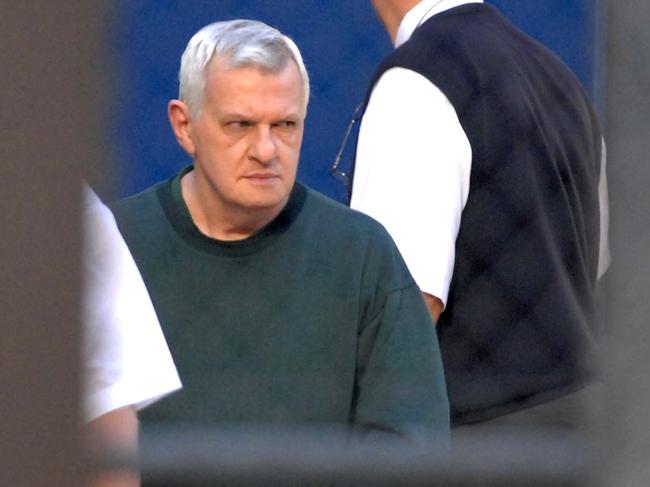

During her time writing the book, from the study of her West Hobart home, Marshall not only interviewed the families of the murdered boys and cast a spotlight on paedophiles as she pursued sexual predators in Australia and overseas, but she also sat face-to-face with Bevan Spencer von Einem, a convicted child murderer and the only suspect who has ever been charged and convicted in relation to The Family murders. Four other young men vanished between 1979 and 1982 and while police suspected von Einem was involved he has denied knowledge/never spoken about them and their disappearances remain unsolved.

A bookkeeper by profession, he was convicted in 1984 for the murder of 15-year-old Adelaide teenager Richard Kelvin.

Von Einem was 37 when he went to jail and had been behind bars for 37 years when Marshall visited, his first visitor from the outside world in seven years.

“It was one of the most challenging moments in my career,’’ Marshall recalls of the moment she sat facing the killer, with no partition between them. “He’s about six foot four (193cm) and I’m five foot one and a half (157cm). And I upset him and I saw the psychopath come up.

“He blamed his victim, this 15-year-old boy who was thrown into a car. A lovely young man who was just trying to get home, he was afraid of the dark, and all he’d done was walk a friend to a bus stop.’’

As chilling as this experience was, Marshall says it’s those sorts of interactions that make her more determined to keep going in her fight for justice, regardless of how difficult writing true crime can be.

“It took me two years to research and write,’’ she says of the book. “And I’m travelling, and I’m alone. And I’m going into places alone and I’m hearing the most horrendous stories.

“The interviews were really, really harrowing. And you carry it home alone too, because you can’t walk away from an interview like that and leave it behind. You sit with it, you sleep with it, you muddle it over until it forms in your mind what you’ve just heard.’’

Marshall says that by the time she finished writing the book she “had to step back from the abyss of possible post-traumatic stress’’. “I appear to be tough … but I’m really soft underneath,’’ she says. “There have been times when I’ve certainly stared into the abyss, when I’ve cried and cried and thought this is not healthy, I’ve got to step back here.’’

She says fortunately she is surrounded by wonderful family and friends who “protect” her.

She has dedicated the book to her “fabulous, vivacious” mother Monnie, who died in 2015 but always encouraged her daughter to “break the silence that keeps the truth hidden”.

“I have times where I’m an absolute mess and the only person who really sees it is my husband William,’' Marshall says. “Luckily I have a great network of people around me.

“I feel like I’m working in isolation a lot but I’m never too far away from people.’

“I also have a heightened sense of fun. I like to cook for friends, dance and read, and we’ve just bought a shack on the water.’’

The shack was an impulse purchase that provided a beacon of hope for Marshall when she was in the emotional depths of writing her latest book.

“It was a really bleak morning when I woke up, in the middle of the book about six months ago, and I said to William ‘I just can’t face another day of writing’,’’ she explains.

So they went for a drive, and ended up buying a shack by the water in the Huon Valley.

Marshall made a pact with herself, that if writing the book became too emotionally taxing she would find a place she could escape to and unwind and try not to think about the murdered boys and the “unimaginable horrors’’ that had constantly been occupying her mind.

And she says the change of scenery definitely helped.

“I’ve fallen in love with it down there, god it’s beautiful,’’ she says.

Marshall is also excited about becoming a nanna, with her daughter Louise Houbaer, a TV newsreader for 7 Nightly News in Tasmania, pregnant with her first child.

“I’m going to have a little person to cuddle and I’m just beside myself,’’ she gushes.

And while Marshall is currently enjoying some well-deserved quiet time after finishing Banquet, her career has showed no signs of slowing down, with plenty more projects in the pipeline.

The ABC has commissioned a four-part series with Marshall upfront as host and investigative producer.

She has also signed with talent agent Mark Morrissey, who represents some of the biggest names in Hollywood including Chris Hemsworth, and has had international interest in her work.

Marshall says there are some very good investigative journalists telling true crime stories.

But she also finds it distressing that crime stories are sometimes rehashed purely for entertainment purposes.

“Unless there’s a reason to tell the story, don’t tell it,’’ she says.

Marshall says she will always be driven by a thirst for justice.

“People often query why I dredge up the past, why I don’t just leave it all alone,’’ she says.

“But this story, as dark and degenerate as it is, must be written. That these Family murders happened at all is terrible enough; that four of them remain unsolved is beyond shocking. Turning away from this story will not make it disappear.’’

Marshall says that once the murders are no longer on the front page, victims’ families often feel a sense of abandonment and loss.

“I just love these people,’’ she says of her brave, grief-stricken interviewees, adding that she feels privileged that they trust her enough to share their poignant stories.

“I love their courage … I don’t know how they keep going, I really don’t.

“In telling their stories, I don’t resurrect their pain for pointless entertainment’s sake. Instead I acknowledge their loss and share their slender hopes that a fresh investigation may bring forward new information that could prove to be a missing link.

“I am a caretaker of their stories, and am always mindful that it is a privilege to gain their trust. I hate injustice and I can’t believe that only one person has been convicted for these murders. The scores of individuals affected by the Family, both victims and their families, deserve better – much better – than to be silenced and forgotten.’’ ●

Banquet: The Untold Story of Adelaide’s Family Murders, by Debi Marshall, will be launched at Hobart Bookshop on Wednesday (September 1) at 5.30pm. Tickets are $5 and numbers are limited. All proceeds will be donated to charity. hobartbookshop.com.au