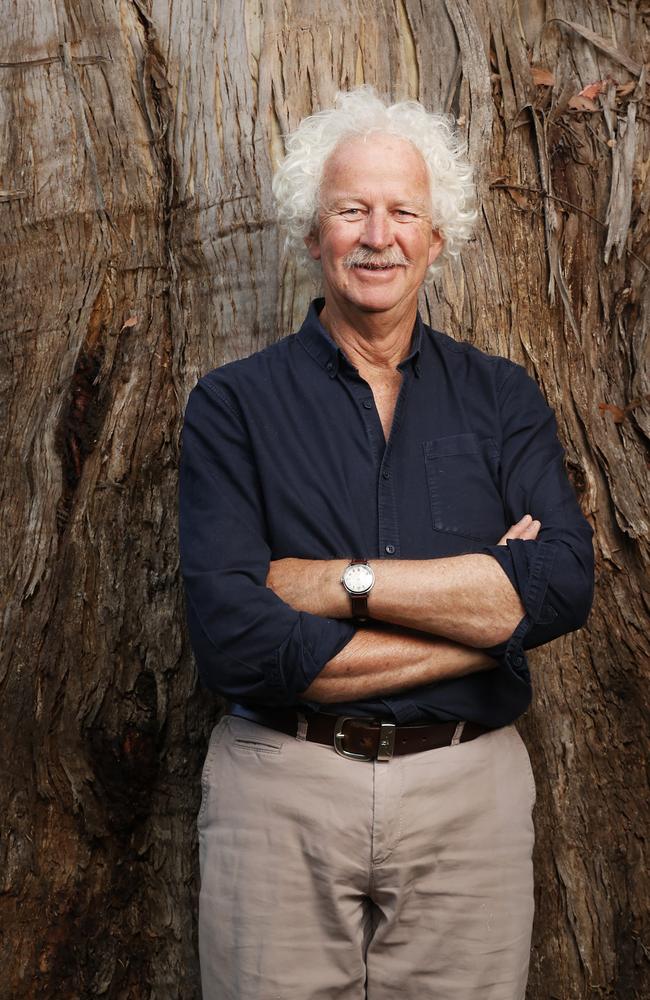

Andrew Darby was deep in Tasmania’s wilderness and also deep in concentration – from footfall to footfall – as he attempted to navigate a difficult-to-follow track through dense bushland en route to Lake Sydney and Mt Bobs in the state’s south.

While he wasn’t lost, Darby found himself relying heavily on sightings of pink tape, which had been left to mark the route taken by intrepid bushwalkers before him.

As the experienced journalist and book author battled his way through thick scrub, he wondered if he’d perhaps been a bit ambitious in his plan to visit some of Tasmania’s oldest – and most remote – trees in his quest to research his latest book.

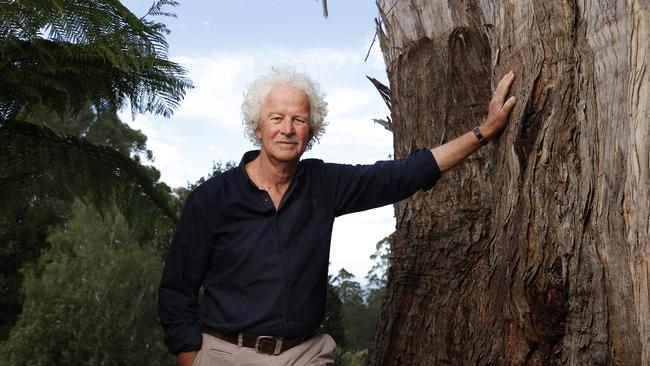

But, as someone who had already faced – and successfully overcome – a stage 4 cancer diagnosis, Darby quickly pushed those thoughts aside, and simply made plans to modify his adventures to ensure he could still get up close to some ancient and magnificent trees and reach his goal of writing a book, while doing it in a way that was compatible with his own physical capabilities.

“This realisation came to me that some trips would be beyond me,’’ the 71-year-old admits.

“But this experience didn’t ever feel that this was too difficult to complete. I just felt I’d have to work my way around obstacles.’’

So that’s exactly what he did, trying his hand at things he never imagined he’d do, in a bid to combat his “disappearing youth”.

Darby took up pilates, to build core strength and maintain flexibility.

He upped his walks with his wife Sally and their two energetic border collies, in bushland around their home at Neika, in the foothills of Kunanyi/Mt Wellington.

He undertook a packrafting course. And he planned his solo walks carefully to ensure he’d get the best possible outcomes.

“One of the issues with writing things about forest conflict for daily newspapers is it’s very deadline driven, you don’t actually get to spend much time out in the forest,’’ Darby says.

“I’d bushwalked as a young person but I hadn’t done much bushwalking since then. But I decided to gear myself up properly and get going. One of the secrets of the ageing bushwalker is to plant yourself in a motel bed nearest to your day walk, so you get a good night’s rest before and after. I ended up trying to be more crafty about my overnight walks … occasionally I’d get spanked by the Tasmanian bush, but I managed to survive it.’'

It turns out Darby not only survived the experience, but thrived – with his new book, The Ancients: Discovering the world’s oldest surviving trees in wild Tasmania, already attracting high praise since it was released earlier this month.

Darby’s writing has been described as “engrossing” and “lyrical elegance”, which “deserves its place on the bookshelf of anyone who loves Tasmania”.

Darby takes readers on an island odyssey to discover the world’s oldest surviving trees, most of which he visited during a series of solo hikes in various parts of the state.

First he seeks the little-known King’s lomatia, perhaps the oldest single tree of all, then the primeval King Billy, pencil and Huon pines – with their vivid stories of admiration and destruction – and the majestic giant eucalypts. Finally he looks at the myrtle beech and Australia’s only native winter deciduous tree, the golden fagus.

On his journey, Darby shares the stories of the people who identified the ancients – scientists and nature-lovers who teased out their secrets and came to respect and protect them.

But, as Darby discovers, lacking defences to fire, these awe-inspiring trees face growing threats as the climate changes.

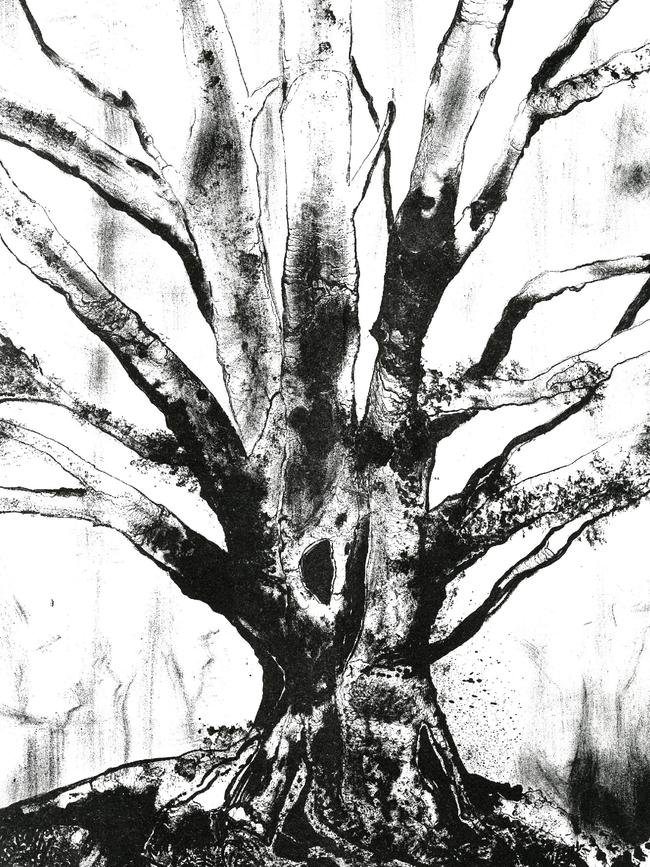

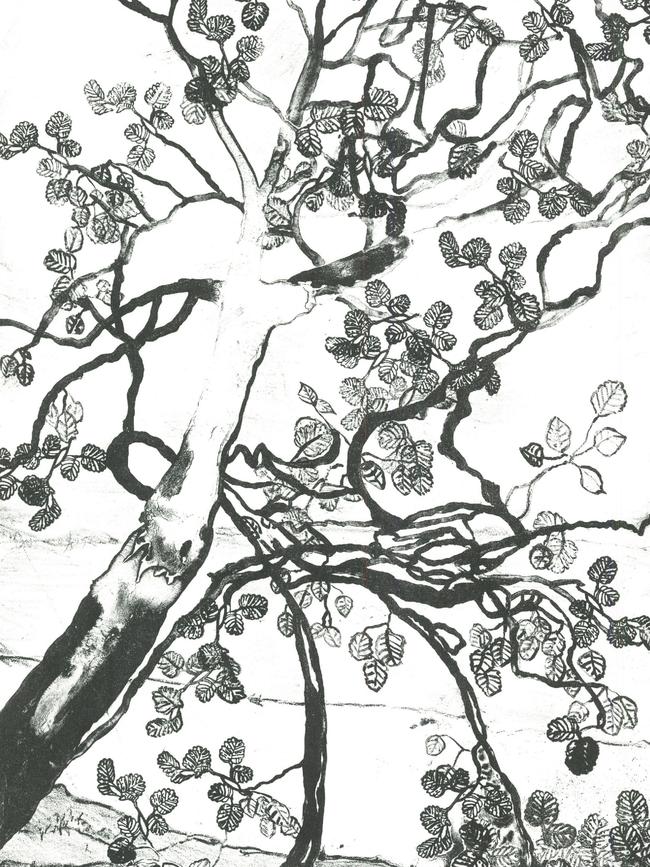

The book features a series of photographs as well as drawings and lithographs by Tasmanian artist Kaye Green, which Darby says “really do capture the vivaciousness and energy of these trees and their lives”.

In many ways the book is a love letter to Tasmania and a tale of hope for the future – and hope is something Darby is certainly embracing in his “second life” since beating cancer.

It’s also a book that may never have eventuated if Darby hadn’t discovered the joy of Tasmania when he first came here to work more than 40 years ago.

Originally from Geelong, in Victoria, Darby worked in various places in Australia and overseas before making a life-changing move to Tasmania at the height of the environmental conservation movement.

“I travelled around a fair bit as a journalist,’’ explains Darby, who worked in Melbourne, London and Sydney, among other diverse postings.

“I came down here (to Tasmania) with AAP (Australian Associated Press) at the end of 1983, just after the Franklin campaign … obviously environmental stories were very hot in Tasmania at the time.’’

In 1988 he left AAP, instead working as the Hobart correspondent for The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald in what he describes as “the heyday of broadsheet newspapers”.

He spent a lot of time writing about Tasmania’s forests and also about issues relating to Antarctica and the Southern Ocean, given Hobart’s position as a gateway to the icy continent.

These interests led Darby to write his first book – Harpoon: Into the heart of whaling.

Published in 2007, the book takes readers on “a global journey to follow the whalers, the campaigners, and the whales themselves, in a balanced handbook on the world’s longest- running conservation crisis’’.

Not content to stop there, Darby then delved into the world of migratory shorebirds, writing Flight Lines: Across the globe on a journey with the astonishing ultramarathon birds.

Research for that book took him to various parts of the world and he was thoroughly enjoying life as a published author.

However partway through writing Flight Lines, in 2017, life took an unexpected turn when Darby returned to Hobart after a trip to China’s Yellow Sea – he began to feel unwell and presented to the Royal Hobart Hospital’s emergency department, which eventually led to a metastatic lung cancer diagnosis.

“I was researching Flight Lines – I was halfway through the research, I hadn’t really begun writing, and I had just come back from China,’’ Darby recalls.

“I’d had a bit of back pain but I thought it was probably from travelling in a mini bus, or something like that. But it continued to get worse so eventually I turned up at to the emergency department at the Royal as the pain transferred around my chest to my heart.’’

Tests cleared him of heart issues, which was a relief, but follow-up scans revealed something sinister – primary lung cancer at the top of his right lung. And, as if that wasn’t shocking enough, subsequent scans showed the cancer was metastatic – it had already travelled to his lymph nodes and bones.

Darby had been a smoker in his younger years, but hadn’t smoked for the 30 years leading up to his diagnosis.

He was otherwise healthy, but admits a career of desk work meant his fitness levels weren‘t as good as they could have been.

Still, he never anticipated a lung cancer diagnosis.

“That was all pretty dire,’’ says Darby, who at that time was given a 12-18 month life expectancy.

He endured radiotherapy and chemotherapy and – most importantly – immunotherapy, which Darby credits for saving his life.

“This new treatment saved my life,’’ he explains.

“Immunotherapy enables your immune system to kill off cancer – it’s a rapidly-developing medical treatment, which I was able to have daily in Hobart.’’

The cancer returned a couple of times while having immunotherapy, but Darby eventually stopped treatment in mid-2020, with doctors confident the cancer was gone.

“I’ve been scanned periodically since then, and now – in 2025 – there has been no recurrence,’’ he says.

During his fight for life, Darby was determined to finish Flight Lines – he finished writing the book while having treatment and it was released in 2020, later winning the Royal Zoological Society of NSW’s Whitley Award for best natural history publication, and the Premier’s Prize for non-fiction in the Tasmanian Literary Awards.

Not content to stop there, Darby was struck with an idea for another book, which is how he later found himself battling his way through Tasmania’s dense bushland, in an attempt to visit some of the state’s most magical trees.

“What happened after Flight Lines was, I had a bit of a look around and obviously an interest in survival is on your mind when you’ve got metastatic lung cancer,’’ Darby says.

But it wasn’t just his own survival he was interested in – it was also the survival of Tasmania’s ancient forests.

Bushfires in Tasmania during 2019-20 – which raged at the same time as Darby battled cancer – had threatened some iconic trees in World Heritage-listed areas, which sent Darby’s investigative mind into overdrive.

“Damage wrought by those fires really hooked me into thinking about climate change and the bombardment of dry lightning strikes across the island,’’ Darby explains.

“This island is globally outstanding for its paleoendemic trees – ancient species that don’t grow elsewhere and have been here for tens of millions of years. Alive today are individual trees that are thousands – and in some cases, many thousands – of years old. There are trees whose direct ancestors lived with dinosaurs.’’

Embarking on three years of bushwalks to research the book wasn’t easy.

Darby intentionally did the walks alone, and made notes while huddled in his one-man tent each night, free from the distraction or influence of other humans.

“I really wanted to be able to engage with the trees,’’ he says of choosing to walk solo.

“I didn’t want it to be too much of a fun bushwalk. I wanted to be able to be elated by the trees.’’

It would have been a different experience, he says, if he’d done the walks with others.

Some walks – like a proposed trip to the Denison River and Truchanas Huon pine Reserve – were scrapped from his initial itinerary when he undertook a three-day pack rafting course in preparation. He was “about twice the age of any other participant” and an experienced guide told him he was “too old, too slow and too cumbersome” to safely complete that trip.

“My guile was not going to make up for my lack of youth and fitness,’’ Darby says with a laugh.

Still, he was grateful for that feedback, which shaped his plans moving forward.

“I was still able to get out to some fabulously wild places,’’ he says.

Not knowing how long he might live also spurred Darby on during the challenging moments. Because although he’s currently in good health, he’s always mindful his cancer could return.

“Given a second chance at life, one wants to make something of it,’’ Darby writes in the foreword of his book.

“For me, it is a contest between ambition and capacity. I revel in my days and pursue a dream unlike some of the friends who sat in treatment chairs beside me and did not share my good fortune.”

He says he could hear the voices of these friends, gently reminding him to “get on with it” whenever he faltered.

So he did.

Darby hopes that just as human ingenuity gave him a second chance at life – with immunotherapy taking what was initially a 12-18 month death sentence and giving him a clean bill of health – human ingenuity may also help save Tasmania’s trees.

“As you would imagine, it was terrible news,’’ he says of his cancer diagnosis.

“But I do really feel that medical science has given me a second life and I’m full of praise for the ingenuity that is involved in medical science.

“What I hope – out of writing this book and talking about how fire has endangered the ancients and how we need to turn this around – is that human ingenuity will come to the rescue of these trees.’’

He hopes experts will be able to invent tools to better understand vegetation patterns and firefighting techniques that will allow them to put out wildfires more rapidly.

He knows it’s “totally unrealistic” to stop all fire in the landscape.

But he remains hopeful that with the “wholehearted support of local government” more can be done to “go to places that need protection” and “keep these ancient trees alive’’.

He also hopes his book will give people – in Tasmania and beyond – greater insight into the value of Tasmania’s forests, which are often taken for granted.

“It is an entirely special island, particularly where its trees are concerned,’’ Darby says.

“I think appreciation of it is really needed – the younger Tasmanian generations need to feel themselves enriched by this, they really should.’’

Darby has also been guilty of not valuing the landscape enough – he wishes he’d spent more time in his younger years exploring Tasmania’s forests and immersing himself in the wilderness, rather than simply reporting on environmental issues from afar.

He says being fortunate enough to stand inside a Huon pine grove, with towering trees that are more than 10,000 years old, had given him a new perspective on life.

And while he’s done writing books for now, his new-found respect for Tasmania’s ancient trees is something that will stick with him for as long as he lives.

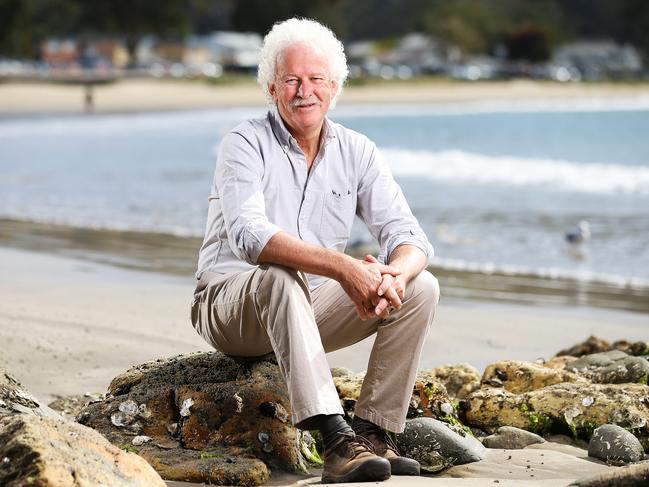

“It’s very rare on earth that you will find a place that is unaltered by human impact,’’ explains Darby, who is approaching five years cancer-free.

“It’s just there, it has lived there like that for 10,000 years, being itself – it’s an awesome thing to contemplate, it’s a marvellous thing to comprehend. I need to take a pause now, I think, and just be able to do things like go out and walk with these trees, to these trees, and appreciate them more, but not feel that I have to be writing about them, but just be with them”. •

Andrew Darby’s book The Ancients: Discovering the world’s oldest surviving trees in wild Tasmania is available now (Allen & Unwin, $32.99).

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Romance boom: Tassie author pens 100th book

Tasmania’s Ris Wilkinson became an author at 44 with romance juggernaut Mills & Boon. At 66, she’s penning her 100th book as Melanie Milburne – as writers converge on Hobart for a national event.

Coal River vineyard dishes up quiet culinary bliss

With a striking cellar door, smart seasonal menu and standout wines this vineyard is a must-stop in the Coal River Valley. Come for the views, stay for the food and a second glass of pinot ...