TasWeekend: Tourism threatens to trample pioneers’ dream for Cradle Mountain

Has the dream of the eco-tourism pioneers who first saw the potential of Cradle Mountain become a nightmare, with 280,000 visitors new descending on the magical wilderness site annually?

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

WOULD the visionary couple who built a remote tourism retreat at what has become one of Tasmania’s iconic destinations be turning in their graves? It was only as she was finishing her homage to Gustav Weindorfer and Kate Cowle that the question began to trouble author Kate Legge. That’s when she lifted her head from her work to realise how much conflict was brewing in Tasmania over the future of wilderness tourism.

As a journalist, Legge’s first response was to write about the storm of resistance greeting some of the proposals arising from the Hodgman Liberal Government’s Expressions of Interest process inviting new tourism developments in the Wilderness World Heritage Area in which Cradle Mountain lies. But she chose not to tackle today’s conflict in her book about the visionary and unconventional Weindorfers.

Instead, the News Corp feature writer did a cover story for The Weekend Australian Magazine on the push to unlock our wilderness. And that got her thinking even more about the enduring tension between tourism and conservation.

“When I started the book it wasn’t such an issue,” says Legge from her Sydney home before a visit to Hobart on Tuesday, when environmental leader Bob Brown will launch Kindred: A Cradle Mountain Love Story at a ticketed event at the State Cinema. “I was in a bubble. I only became aware of the heat as it was going to press.”

Now she cannot stop thinking about the resonances between 100 years ago — when wilderness tourism was flagged as a conservation measure and a boost for feeder towns — and today, when it is again touted as a ticket to prosperity and a way of winning people over to the conservation cause.

“With the state on the bones of its arse for so long, you can see why Hodgman is rubbing his hands together,” says Legge, calling for a measured and sensible way forward. “It can be done without spoiling it, if we check the turbo-driven capitalist urge.”

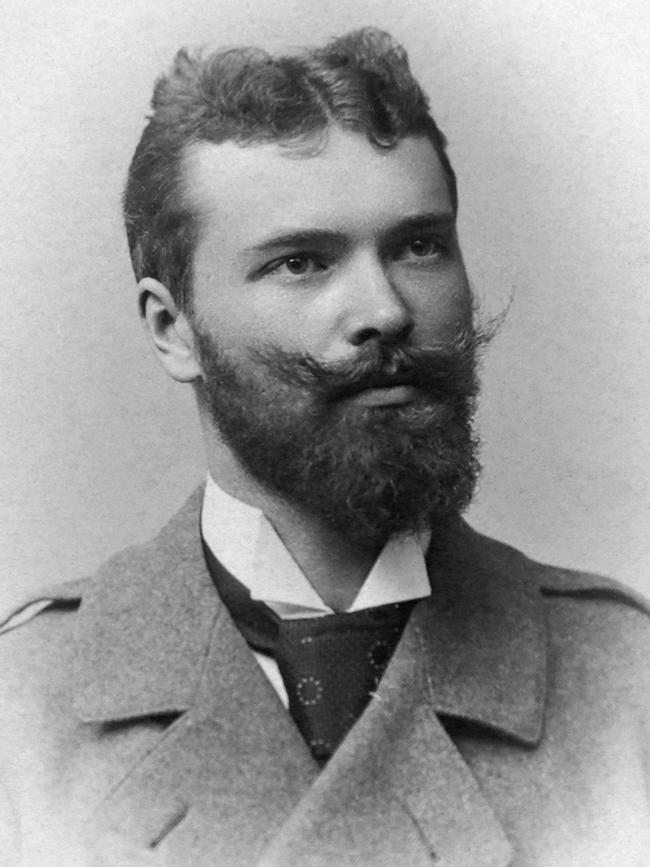

It was a love bubble indeed when Tasmanian Kate Cowle and Austrian immigrant Gustav Weindorfer, 11 years her junior, came together. He grew up in the alps and “she climbed mountains when few women dared,” as Kindred’s dust jacket sings. The couple met at a gathering of amateur botanists and naturalists in Victoria. On their honeymoon, “a glimpse of Cradle Mountain lit an urge that filled their waking hours,” Legge writes. “When they stood on the peak in the heat of January 1910, they imagined a national park for all.”

Kindred traces the lives of the couple as they built their beautiful Waldheim chalet deep in the wilderness, pioneering a type of eco-tourism that’s still an ideal today, combining hardy day walks with lively conversation, wild-caught meat in hearty meals and comfortable beds back at base.

“They were creatures of their time,” says Legge, scientists and dreamers filled with the kind of yearnings that had inspired nature prophets such as writer Henry Thoreau and founding father of Yosemite National Park John Muir. “It was the beginning of the National Park movement in America, they were part of a naturalists club in Victoria, and they were early visitors to [retreats] at Mt Buffalo and the Hermitage in Victoria, so they had an insight into what could be achieved,” says Legge. The Cradles became their canvas.

Along with their utopic dream they had “the idea that the bush didn’t have to be a forbidding place where you were likely to be bitten by a snake, but a glorious place,” says Legge.

She is a journalist and author, not an activist, but Legge says she feels compelled to honour the legacy of the couple by speaking out now. She is troubled by the prospect of more huts and other infrastructure being built in the World Heritage Area.

She believes the Weindorfers would say it’s time to pause, reflect and reassess. Their mission a century ago was to show the world the jewel they had discovered to help protect it through a National Park listing. Sure, they wanted to make a living doing so, but the plan was not to unleash a juggernaut.

“They weren’t just tourism boosters,” says Legge. “They were botanists and nobody else was marrying science to scenery in Tasmania. They saw [their work] as a convergence of the two things. And because of their interest in science and biodiversity, I think they would have been disturbed by further encroachment of private lodges into these public parks. They wanted to share Cradle Mountain, but that was at a time when there were 150 people a year coming through.”

That compares with 280,000 people visiting Cradle Mountain - Lake St Clair National Park in the 2018 financial year. “Maybe it is time to consider some sort of cap on numbers as one management tool,” Legge suggests, to help preserve the tranquillity of the experience as well as the environment.

Legge wrote in her magazine piece in November that when Tasmania first allowed private huts to operate beside public huts along the Overland Track 30 years ago, about 84 people walked the 65km track a year. Now 9000 people do it, with the Tasmanian Walking Company using private shelters to cater for a select few on its signature Overland Track huts walk.

Legge says that where the Weindorfers looked at nature with awe, humility and fascination, people’s “hyperawareness” of nature seems different today.

“The more disconnected with nature [big-city dwellers] become, the more we seek it out … We feel a hunger to feel this tranquillity and feel these spaces. That’s the popularity of these guided walks, but at the same time we have to make sure that in our lust to reconnect with nature we don’t spoil it.”

A keen walker who enjoys guided hikes, Legge says spending a year absorbing the Weindorfers’ perspective led her to see things differently. “Everything. I felt they taught me to see trees and understand the difference between individual trees and to understand the make-up of our landscape, which we have been so brazenly ignorant about.”

She loves the enduring peace of Tasmania’s alpine environments. “I feel restored, soothed, at peace. Especially at Cradle Mountain, I feel totally enthralled by the melancholy key of the landscape.”

Along with the power of the place, while researching and writing Kindred Legge also felt an affinity with its unconventional champions, who were the talk of the town back in the day for their unusual relationship, interests and habits.

“I am a quarter German, and Gustav had so many qualities I relate to — industriousness, energy, drive, precision. I am afraid I walk like him, up and down Mt Roland and back in a day,” she says. “My mother often pretended her mother was Irish, not German [because of mid-century anti-German sentiment] but those Europeans really lifted the scales from our eyes when they came here.”

As for Tasmanian Kate? “I thought she was amazing and unbelievable,” says Legge.

“The fact she was so bold and brave and so independent, going to Melbourne to live as a single woman. And yet once she married Gustav, though they shared a vision, she was very much still the woman in those days. There were compromises she had to make …”

Kate, like so many women, was all but written out of history, says Legge. “He was the big bold person, but it was their shared vision, and there was so much she did to facilitate their dream, including buying the land for it.”

In telling their story, Legge was just as interested in bringing Kate into the light as she was in the conservation story. The author, who lives in Melbourne, became intrigued three years ago when one of her two sons took her to Cradle Mountain after the break-up of her marriage to media executive Greg Hywood on the eve of their 30th wedding anniversary.

“I was on a melancholic ramble when I veered right and wound up at the door of a wooden chalet, a replica of Waldheim, the forest home,” she says, laughing. At first, she planned to write the lovebirds into a novel, but decided that would miss an opportunity to pay real homage to them. “I wanted to bring them to the notice of more people. That was the defining interest for me – to celebrate,” she says.

Legge was attending a tourism function in Hobart last year when she realised how invested in the Weindorfers’ legacy she had become. One moment she was chatting merrily away over drinks and canapes and the next she was shaking with emotion on the waterfront. The trigger was an established tourism operator mentioning that his company was hoping to build a chalet by Lake Rodway in Cradle Mountain - Lake St Clair National Park.

“I went outside, I was shaking, utterly bereft, so upset they were planning to do this,” she says. “I was shocked as a journalist to feel so strongly, but it was an awakening for me, thinking perhaps I needed to take a stand, too. I feel I can defend it because of all the research I’ve done into what drove Gustav and Kate, their incredible legacy and custodianship.

“There is a greater good here than making money for shareholders and company owners. We are the shareholders and owners and we need to muscle up and demand the Government listen to the people on this issue.”

Spend a few minutes with most nature tourism operators and they will almost invariably tell you how their business is really good for conservation, because their awestruck clients become advocates for the destinations.

In simpler times when recreational wilderness travellers were relatively few and far between, it seemed a sound argument. But it is seeming increasingly specious to Legge as nature tourism grows… and grows.