TasWeekend: Master strokes

ARCHIBALD Prize-winning artist Geoff Dyer’s studio paints a picture of a restless talent striving for his idea of perfection.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

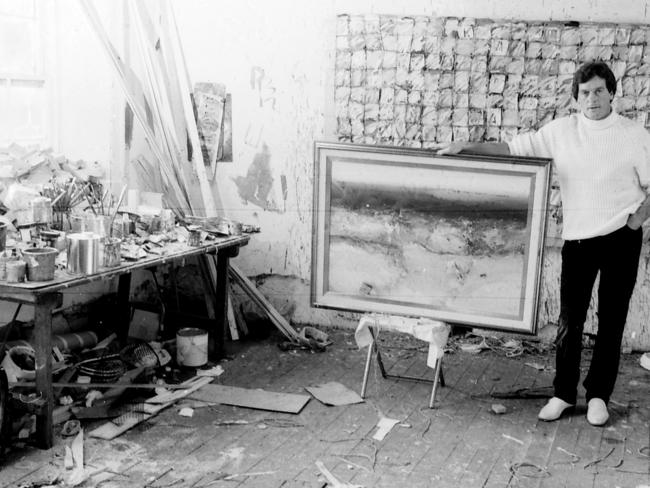

LANDSCAPE artist Geoff Dyer’s North Hobart studio looks exactly as you might expect a passionate painter’s workspace would. After climbing seemingly endless stairs to the top floor of the historic industrial building, we enter a spacious loft drenched in diffuse light.

The air has the musky scent of old oil paint mixed with the tang of turps and thinners, emanating mostly from a pile of used rags discarded in a corner. Scattered tables are crammed with paint tins, some shiny and untouched, others dinged, stained and lidless. On one table sits an obsolete cathode-ray-tube TV, spattered with paint and too heavy for the artist to carry downstairs to throw away. The floor is sticky with spilt paint. Huge canvases are stacked against the walls, sometimes six-deep. On the wall where the Archibald Prize-winner does most of his work, a big canvas bears the image of a stormy seascape, beneath it virtual stalagmites in wild colours growing from an accumulation of dripped paint.

As we talk, seated in paint-splashed armchairs, Dyer trails off and looks over my shoulder, a repulsed look on his face. “I bloody hate looking at that thing,” he says. “I’m not happy with it. I’m going to paint over it, start again.” Throughout the interview, his gaze repeatedly returns to the seascape and each time he hisses an obscenity at it before laughing.

Perhaps Dyer’s tendency for self-criticism has served the 68-year-old well, though; he is among the most highly regarded landscape painters in the country. Responding to his fear of becoming a “recipe artist” working to a formula and producing the same thing over and over, Dyer constantly shifts his style in subtle ways, always experimenting. As a break from landscape painting, he turns to portraiture, also to acclaim.

“Lots of artists are victims of their own success – they become subordinates to their own fashion,” he says. “I don’t want that to happen to me.”

Dyer favours large canvasses, wet paint worked into wet paint, thick oils creating a topography of raised ridges and whirls applied with knives instead of brushes. He often draws strange beauty from unlikely subjects such as polluted rivers and burnt bushland. As he shows me the work in his studio, he constantly trails his fingertips over the paint.

“I paint from the shoulder, big paintings,” he says. “I don’t paint necessarily in the manner of frenzied aggression but it is very physical for me – the big canvasses, lots of physical exertion, it’s my exercise.”

Dyer was born and raised in Tasmania, growing up in Moonah where his father worked as a motor mechanic. He cannot remember a time he wasn’t interested in painting and drawing, doing his first oil painting when he was about eight – and he still has it.

But his art took a back seat at high school, when he focused on maths and science. However, he soon rediscovered painting and went on to the Tasmanian School of Art in Hobart in the late ’60s.

He then became a teacher, posted first to King Island, then Launceston, Cressy and Hobart. He painted everywhere he taught.

“King Island was one of the best years of my life,” he says. “I was coaching the footy side and I did a few paintings while I was there.

“It was also where I painted a portrait of an old fellow who was 96 and had never left King Island. I never thought much about it at the time, but that was quite amazing. He would have been born on that island in 1870-something and he never ever left it.”

Dyer’s last school-teaching position, in the mid-’70s, was at Elizabeth College (then Elizabeth Matriculation College), a stone’s throw from his studio today. After several years as an art tutor at the UTAS art school in Launceston and later at Burnie Technical College, he quit.

“By that stage I was about 30, I knew it was now or never,” he

says. “I needed to take that leap and be a painter. You need to do it at an age when you’re still stupid. Well, impetuous, maybe.

“I’d had some success with a couple of paintings in Sydney, not much but enough to exhibit one in the Wynne Prize Galley in NSW while I lived in Burnie.

“I moved to Hobart, I had some gallery connections in Sydney and Melbourne, and at the time I was doing a lot of works on paper, which meant I could work quickly and produce a lot of paintings to be sold and shown interstate. That allowed me to make a living from painting for the first time.”

Dyer spent about 20 years travelling between Hobart, Melbourne and Sydney, building his reputation as well as his skills.

“When I first went to Sydney I had a little studio at the Rose and Crown Hotel,” he says. “Upstairs were people like [artist] Brett Whiteley. It was a but unreal. Suddenly I was meeting other painters, learning very quickly. But after 20 years of Melbourne and Sydney I came back here to Hobart. Basing myself out of here and still reaching to the bigger cities is something you couldn’t have done 50 years ago.”

Dyer found his current studio not long after he returned to his home town.

“It’s nothing glamorous, it’s just a working space,” he says. “But

as soon as I saw this place, that was it. Before this, I’d never been in the same studio longer than two years, but I’ve been here 15 now.

“I need some space because of the scale of my work. It’s isolating in its own way, being here, but it’s still part of the city. If I went back to Sydney or Melbourne I would never get somewhere like this in the city. I’d be out in the backstreets of some suburb somewhere and it would be horrible. I’m too old for that.”

He glances around the multicoloured mess.

“My home is spotless, you know,” he laughs. “I’ve never worked from home unless I’m in transit or something and have to work in the kitchen.”

Dyer has been a finalist for the country’s most prestigious prize for landscape painting, the Wynne Prize, nine times.

“When I was young, I visited the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery a lot and you go to the things you can understand,” he says.

“To me that was the colonial art room, which until recently was always the same every time I went. Those old dead brown and gold paintings of the past, that was the first intro I had to any kind of artwork outside my classes. I grew through all that, those traditions.

“I was doing some figurative work [portraiture] for a while but found myself drawn back to the landscape – sometimes abstract, sometimes derivative – but I find myself always surrounded by landscapes. I notice them. I can’t imagine painting cityscapes or being part of that figurative group, it’s not what I do.”

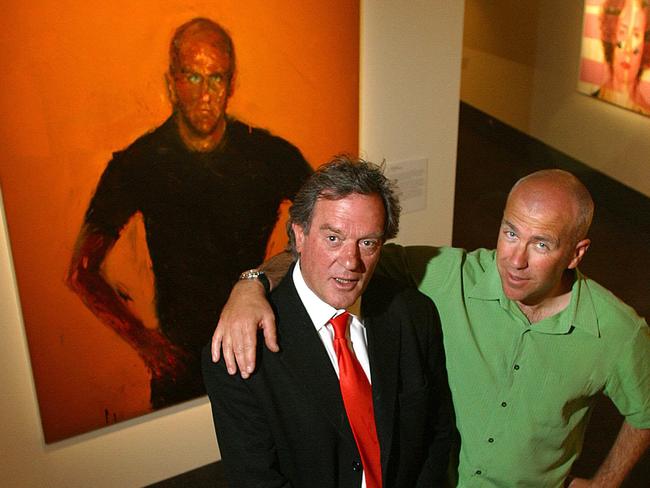

It’s an interesting thing to hear from a man who has won the Archibald Prize for portraiture and been short-listed for it six other times (along with twice for the Sulman Prize). He laughs when

I say so and shrugs, saying he was lucky to have had some excellent sitters for his portraits, including former Greens Senator Bob Brown. But he says he generally finds portraiture a bit limiting and sometimes troublesome.

“I’ve had some wonderful sitters – I’ve been very lucky and it’s been a pleasure,” he says. “But it’s not always easy. You know, a landscape won’t say, ‘Geoff, unfortunately I don’t look like that, I’m not happy with it’. Hopefully, you paint people with an aesthetic understanding that portraiture lies within the boundaries of this and that, without flattery and so on. I get asked a lot but I don’t do commissioned portraits because, although you sort of get free rein, people are used to looking in a mirror and seeing themselves in a certain way and that doesn’t necessarily match what I paint.”

He says most of his early portraits were painted as small commissions for friends when he was teaching and he rarely took them seriously. The first big portrait he painted was of Brown for

the Archibald Prize, which was a finalist in 1993.

“Once you’ve been in that prize and seen your work hung on the wall [at the Art Gallery of NSW in Sydney], you get hooked,” says Dyer. “Until you win it, then you’re no longer hooked at all because you realise the fickle nature of it.”

The winner he refers to is his portrait of Tasmanian author Richard Flanagan, which won the prize in 2003. “Winning that prize was a wonderful moment. You never forget something like that. It gave me a bit of a push,” says Dyer,

This striking image of a dark-clothed, stern-looking Flanagan against an orange background still holds a special place in Dyer’s memory, not least because Flanagan is a friend.

“When I finished it, I invited a couple of people up to look at it for their opinion, because it had come together really quickly and I really wasn’t sure if it was any good,” he says. “Richard hadn’t seen it yet. So when he found out I’d been showing it to others he phoned me and said, ‘Everyone else has seen this bloody thing except me – I’m coming up’. And when he saw it he told me I’d nailed it.

Dyer enjoys the company of his subjects, immersing himself in their stories.

“[Gallipoli veteran] Alec Campbell, for instance, the guy was more than 100 years old – I mean, that’s remarkable, the things he experienced. And that painting was about Gallipoli as much as it was about him. It was a reference, a story.

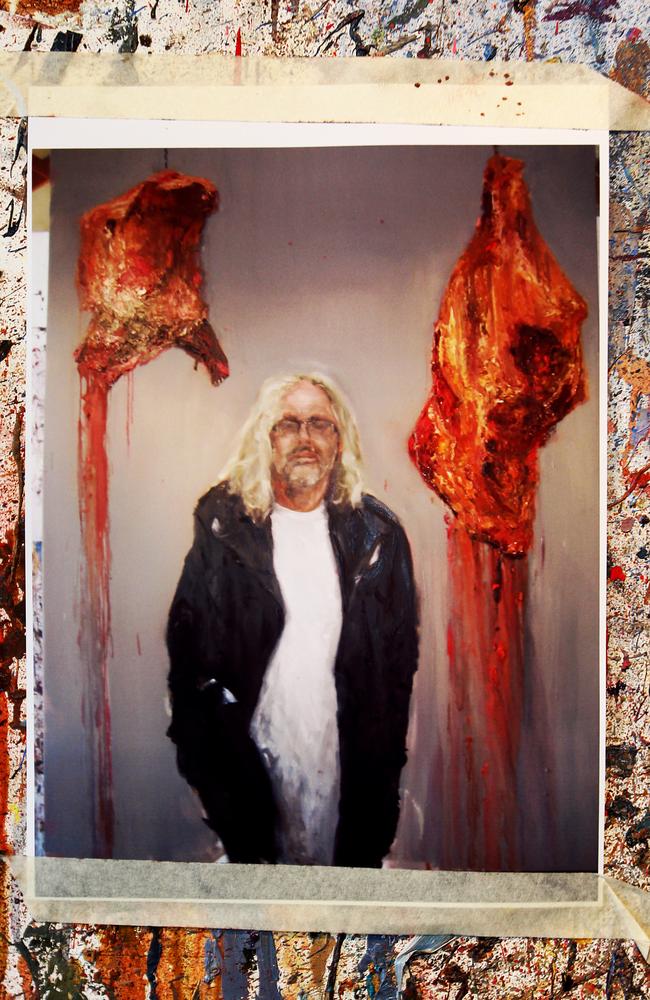

“I won’t be doing any more Archibalds, though. I’m done. After I painted [Mona owner] David Walsh [a finalist in 2011], I think that was the zenith of it for me. With that one, I couldn’t have done any better. Maybe something will happen in the future but I would have to be overwhelmed by the subject. (I painted David twice, actually. The first one, which he now owns, wasn’t hung. It was an abstract to a degree.) But I just can’t find a way to make a relevant statement through the figure [anymore]. I can do that with landscape though, I think.”

As if to prove his point, his 2000 Archibald Prize-finalist painting of [author] Christopher Koch is neglected at the rear of the studio, among a stack of other “failures”. Like everything else in the room, the canvas is spattered with paint. “I’ll probably paint over that as well,” Dyer says dismissively. “Christopher always hated it, anyway.”

At the time of my visit, Dyer is working primarily in shades of blue and black, creating a series of nocturne seascape images of Ocean Beach on the West Coast for an upcoming exhibition. Each painting starts out as a canvas painted entirely black and then he works fresh paint into the wet background, gradually bringing the image out of the blackness. His fingernails are stained a pale shade of blue.

He says he paints from memory and photographs of the places he wants to paint, but the photos serve to inspire and jog his memory – he never tries to simply reproduce them.

Dyer works an average of five hours a day on his painting, saying there is a strong element of chance to his art.

“Sometimes it’s like going to the casino and playing the wrong numbers,” he says. “You take a chance when you paint something.

“It’s about your ability to grasp the chance and use it. If, somehow, you are lucky enough to seize that chance and transmute it and the gods are with you, it’s good fun. If it doesn’t happen, then it’s not much fun at all.”

Geoff Dyer’s new exhibition Waterline opens at the Despard Galley, upstairs 15 Castray Esplanade, Hobart, on Wednesday and continues until March 16.

For more great lifestyle reads, pick up a copy of TasWeekend with your Saturday Mercury.