TasWeekend: Kirsha Kaechele’s new cookbook offers a tasty solution to our pest problems

Cane toad, fox, and myna bird parfait ... is there Kirsha Kaechele won’t eat?

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

KIRSHA Kaechele wanted to taste cane toad, so she placed an order with toad hunters in northern Australia, expecting a batch of skinned legs to be dispatched. The plan was to sweet-and-sour the limbs to sample ahead of the recipe’s inclusion in her new cookbook on invasive species, Eat the Problem, which comes out on Monday.

“They had to be dead,” Kaechele says of the consignment of the reviled invader species, which was introduced to Australia from Hawaii in 1935 to take on native beetles feasting on sugarcane crops in Queensland, and which continues to spread.

“We didn’t want any quarantine issues or to start a toad invasion in Tasmania. I think it’s too cold [for them to survive here], but you don’t want to risk it. I thought the collectors were going to lop off the legs, like you are supposed to, right away, skin them, soak them in salt water then freeze them and send them to us. But in fact they sent the whole dead frozen toads and the deadly venom in their glands had seeped all over the bodies, which made it extremely unappetising.”

After washing the toads, they were prepared to a recipe contributed to Eat the Problem by former chef and Arnhem Land tour guide David McMahon, who says they are delicious and “if you can’t beat them, eat them!”. The thought of the toxins gave even the insatiably curious Kaechele pause, though.

“I consulted four websites [by cooks who] serve them all the time. They say only a fool would be afraid, it’s just a stigma. But meanwhile a scientist I spoke to at the University of Queensland said he wouldn’t eat them, and I included his warning just in case. People can make their own choices.”

Indeed, they can, and what fun it is to do so as you flick through Eat the Problem. Coal-roasted pussy cat for breakfast? No thanks. Fox curry? Maybe not, I don’t eat dog. Well, could I tempt Madame with slices of whole-roasted camel stuffed with a large goat and 30 pheasants? Not right now, thank you, I’m just so full. OK then, starfish on a stick it is.

A change in perspective rather than a dietary overhaul is really the point of all this, though many of the dishes included are less confronting than the star-performing shockers, featuring meats such as venison and rabbit, which are unlikely to give many Tasmanians the heebie-jeebies.

An early copy of her 544-page hardback sits on the long table between us at Kaechele’s Battery Point penthouse. It is an epic labour of love she has worked on for five years. Each recipe revolves around an invasive species that has wreaked havoc where it has been introduced. Many, like the cane toad, were released intentionally but misguidedly. Global warming has shifted others to new pastures with devastating consequences.

The contributors list is a star roll call including James Turrell, Marina Abramovic, Germaine Greer, Heston Blumenthal, Pablo Picasso, Enrique Olvera of Pujol, Tetsuya Wakuda, Tim Minchin, Peter Gilmore of Quay, Yves Klein, Matthew Barney, Salvador Dali and many more.

Yes, some of them are dead, but in their lifetimes they shared Kaechele’s fascination with unusual ingredients, and none more so than wild Surrealist Dali, whose recipe here calls for 100 snails – one of his enduring symbols – and a bottle of Chablis.

Are punters actually meant to cook these crazy concoctions? The pristine white cloth dust jacket, which would last about two minutes before getting tomato-splotched in most kitchens, suggests the book is bound for coffee tables where its environmental message can be mulled and discussed by a cognoscenti that will also appreciate the breathtakingly beautiful photography and styling of the most bizarre offerings they may ever see.

There is plenty of illuminating reading beyond recipes, with numerous essays, shorter pieces and interviews. Ever wondered why a hunter commissioned to cull feral pig and goat in national parks might spare some pregnant sows and nannies? Well, he wouldn’t want to diddle himself out of next year’s work, would he, suggests biologist and author Tim Low. How do you go about tracking feral cats in the desert? John Tjupurrula West tells Josephine Nangala how he hunts in an interview conducted and transcribed in his aboriginal language, with an English translation also provided.

Unlike most people’s creative projects, which are typically ambitious in conception and then scaled back as reality strikes, Kaechele’s book grew wilder as it went.

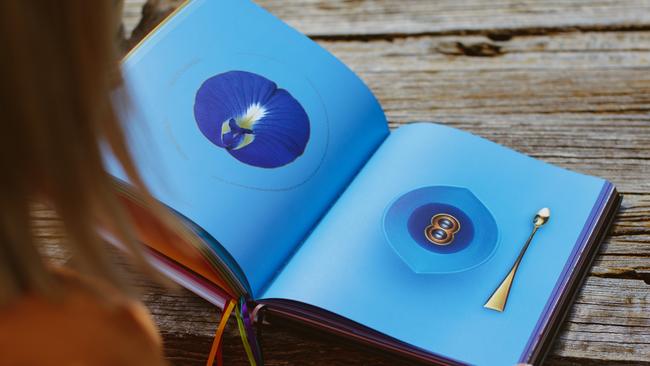

“It was always a rainbow, from the beginning,” she says of the multi-coloured stock on which key ingredients are matched to page hues. Think pink for buffalo tongue. “It was more of a foodie bible to begin with. I was focusing on Tasmanian food in general, and celebrating terroir and foraging. It emphasised weeds and eating the problem, but included other ways of eating off the land in a meaningful way, too. Then I realised that ‘eating the problem’ was much more fun and I should narrow it down to invasive species only.”

As I sit with her, I have to remind myself Kaechele came into collector and philanthropist David Walsh’s world fully formed. Clever, curious, iconoclastic and with a mesmerising manner magnified by her dreamy Californian lilt and the delightful sense she is full of surprises, she’s a weirdly apt embodiment of Mona itself – so much so that it’s tempting to imagine she simply came to life one night at the museum.

In fact, Kaechele’s relationship with the Museum of Old and New Art’s founder predates the 2011 opening of Australia’s biggest private museum, and she has been an integral part of its activities from the start, often expressing herself through collaborations involving food, art and community development.

At grassroots level, these include her acclaimed 24 Carrot food-growing program at schools in disadvantaged areas and Heavy Metal, an art-science project focused on mercury contamination in the River Derwent. At the high end are the spectacularly decadent performative feasts she conceives and directs as artworks in their own right, rejoicing with her husband in what they see as the rituals’ transformative powers.

“He feels great when he sees the apparitions,” she says. “It is completely cathartic for both of us, and for everyone, really. I am very scientific, but there is a spiritual dimension to the feast. It’s choreographed, it’s a performance, and as a guest you become part of the work.”

Kaechele conceived their daughter Sunday after their lavish fertility-themed wedding feast in 2014. “The whole thing just symbolised soft, gorgeous femininity and was sublimely beautiful. It’s no wonder we had a girl,” she says.

She says the feasts she is planning to celebrate Eat the Problem and its accompanying exhibition will outdo even the wedding feast. “I think this one coming up is going to be even more powerful,” she says.

She may talk up myna bird parfait washed down with a boar’s eye Bloody Mary, but Kaechele’s daily diet is quite tame, as it turns out. For the record, she didn’t eat the placenta after the birth of her only child, in 2015. And her husband is vegetarian.

“He doesn’t like to kill anything that has a mind,” she says. “And I say I don’t like to eat anything that I am not willing to kill, but I am very comfortable killing an oyster. Or a scallop. Or even sardines, though I feel a little bad about sardines. But I don’t like to eat tuna because I am not happy killing it. I can’t kill a tuna. They are too big.”

She doesn’t tend to eat red meat. “David and I both had a little bit of deer from our property [at Marion Bay, where the introduced species suddenly appeared a few years ago], just a few bites. If you are going to eat meat, that’s the sort of meat it makes sense to eat. So who knows, it could convert us.”

She is riled over restrictions in Tasmania that prevent wild-caught deer meat being sold in restaurants and is agitating for regulatory changes to venison sales. For now, it is served at Mona only at private functions.

There’s no fox on the menu, though, and not just because there are (apparently) no foxes in Tasmania.

“We have a fox recipe in the book, contributed by Englishman Fergus Drennan, but I am not that excited about fox meat. It sounds as if you are doing a lot of prepping and boiling of the meat, and you use a whole lot of spices to cover the flavour.”

She is convinced by fox fur, though.

“I mean, who isn’t?” she says, running her pale gold-ringed fingers over a foxy fashion spread in the book. “Look at that. Come on, that’s gorgeous!”

It was seeing fur go to waste that inspired Kaechele to look creatively at invasive species. Then, as now, the challenge of turning flaw into feature — or in poo-obsessed Mona parlance, shit into gold — excited her. It was rat fur prospects in particular that got her going.

This was pre-Mona, back in the US where she comes from via a childhood spent partly in Guam and her coming-of-age years roaming the world on a self-educating quest, embedding herself in knowledge-seeking communities in different countries.

She was living in New Orleans in the noughties when she started hearing about a big, orange-toothed rodent destroying the swampland of Louisiana by eating away vegetation at its roots. County sheriffs were offering an $5 bounty on the tails of the nutria, but the shooters were leaving the guinea-pig-size carcasses to rot in the swamps after removing their prize from the animals’ hindquarters.

“It was controlling the problem, but it was so shortsighted because here was this amazing resource,” says Kaechele.

“If these creatures were already being culled, then it was shameful to waste their fur and their meat. So I invited artists to work with the nutria. Some made fashion and there was a huge attempt to popularise nutria as a food, but I didn’t succeed. I wanted to have a nutria sausage stand for the New Orleans Biennial 2008, but I didn’t manage to pull that off because no one was quite up to the task.”

She turned to high-end designers to try to popularise their fur. “All that was missing was relationships with fur-processing plants and high-end designers, so I contacted labels like Fendi and Marni. Who knows what my success was, but they certainly did come out with lines,” she says, predicting nutria’s time is now. “Maybe that was a little too early for the consciousness of the fashion industry.”

This was also the era Kaechele launched the Life is Art Foundation, which exhibits site-specific installation art and became the platform for her now-famous immersive feasts.

She says the world has warmed to the notion of eating pests since she started working on the book five years ago. “Then it seemed like a radical idea to eat invasive species and now I think people are pretty ready for that. It’s not as confronting and it just seems to make sense.

“So many of the foods we view as pests are popular in another cuisine and part of a whole culture. It’s just that we didn’t evolve with that particular animal, so we don’t have a culinary tradition built around it.”

While the book is global in conception and content, Tasmania and its problematic introduced species are a strong presence. Sea urchin is well-covered and of particular concern to the author, with warming sea temperatures luring the long-spined urchin south from its native NSW.

“Sea urchin is having a devastating effect on the ocean floor around Tasmania and most people don’t see it,” she says.

Since the first long-spined urchin was discovered off St Helens on Tasmania’s East Coast in 1978, the population has exploded to an estimated 20 million here to devastating effect. Its overgrazing of kelp and seaweed beds leaves them barren, with few of the species required to maintain the underwater desert.

Measures under way or in the research phase to control the invader include bolstering the rock lobster population, with this most effective predator itself at risk from overfishing. Other ideas in the works include large teams of divers literally smashing urchins; robot culls with automatons able to identify and kill the offending species; and incentivising the harvest.

Naturally, this is what lights Kaechele’s fire. Many chefs were keen to use sea urchins as their hero ingredient in Eat the Problem. “That was the number one request because of the culinary potential,” says Kaechele, though some say the long-spined variety is unpalatably bitter. “Every chef knows how delicious urchin is, it is divine. It’s a delicacy, and the Japanese have been celebrating it forever. They are desperate for it and it is overfished in Japanese waters.”

And yet in Tasmania, there is a negligible commercial urchin fishery, with no size nor catch limit for the problematic long-spined urchin (Centrostephanus), as opposed to the native short-spined urchin (Heliocidaris).

“It’s an incredible opportunity,” she says.

Invasive plants are a focus of the book, too, with Kaechele raving about Mona head chef Vince Trim’s dessert flavoured with the flowers of declared weed gorse. Trim was a key collaborator on the project, contributing and cooking not only his own recipes for photography but preparing a number of those contributed by others and travelling to Mexico with the author.

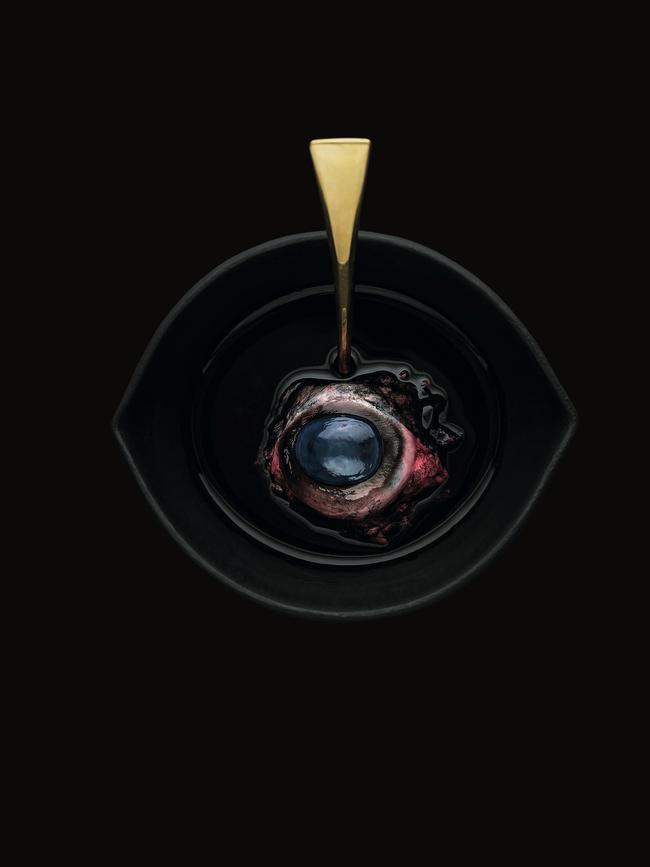

Kaechele also worked closely with Mona photographer Remi Chauvin, who shot most of the food dishes while she tweezer-styled on various locations around the world as well as back in the Mona studios. “He has extraordinary patience and he seeks perfection,” she says. “He was willing to allow me to angle a flower petal 1mm and shoot it again. We really just obsessed over each image together.”

The book reprises pieces of Kaechele and Walsh’s wedding tableware, including gilt vagina bowls crafted by Studio Zona and solid gold cutlery co-designed and made by Natalie Holtsbaum, a long-term collaborator and one of many individuals Kaechele has invited into projects over and again, enjoying the synergy. Superlative graphic design is by Matthew Walker.

With the book completed, Kaechele’s focus is on feast preparations. “It will be a living installation,” she says. “Guests will eat the rainbow, eat the problem course by course, each course in one colour, through a nine-course degustation.”

With extraordinary financial and creative resources at her disposal, Kaechele acknowledges her privileged position, well aware how few people ever get to see their most ambitious, not to mention outlandish, visions realised. How does it feel?

“It’s amazing,” she says. “I’ve always done [these things], but now I get to do it and preserve my mental health. The feasts have a long tradition. They predate Mona, and it was really difficult then because I had to fundraise and be extremely resourceful. Now we have the entire Mona team who are into it, and there’s so much talent that it’s easy now.”

What about the proverbial necessity as the mother of invention? Is it intimidating to have an open canvas and do you miss making do? She admits it took some getting used to, this cashed-up life with Walshy.

“The first time I did a feast at Mona, the shock was the lack of suffering,” she says.

“In the past I’ve had to do physically so much to make these things possible and because the team here is extraordinary I just didn’t have to. And I felt confused, disoriented, and I wondered if I’d done anything.

“I didn’t have the same satisfaction, actually. Even though it was probably more extraordinary than the events I’d done before, I didn’t have that same feeling of accomplishment. I had to get used to that.

“And now I am used to it and feel entirely confined again,” she adds, laughing. “I still need a budget that is 10 times larger. It’s completely relative. I’m like ‘oh, I really need it to be made out of this material’.”

It is the creative process itself that she says she most relishes. “It’s the joy of envisioning and creating and the push to make it happen, and there’s never enough time so there is always this buzz among the artists, and it’s terrifying but delightful and you are just sort of drunk on the process.”

In ancient folk story The Frog Prince, a princess grudgingly befriends an ugly frog from whom she requires a favour. Depending on which version you read, she transforms the cursed creature back into original form as a handsome prince either by kissing it or hurling it against a wall in disgust.

Eat the Problem ma y well generate both responses, but for Kaechele the fairy tale rolls on as she awaits delivery of a gown she will wear to the launch feast. It is being sewn now in a majestic patchwork of cane toad leather. ●

Eat the Problem, an artwork by Kirsha Kaechele, Mona Publications, $277.77, comes out on Monday. On April 13, Mona will also launch an Eat the Problem exhibition accompanied by a series of feast events, for which tickets will be available from Monday.

Proceeds from the book will be donated to Kaechele’s healthy eating program, 24 Carrot Garden Project, which has set up kitchen gardens in primary schools around Hobart.

For more information, go to mona.net.au