TasWeekend: Geoff Dyer revels in a renewed sense of vigour

There’s a certain urgency in Geoff Dyer’s work but there is also a new determination and purpose, as Tasmania’s greatest living artist – about to feature in not one, but three major exhibitions – puts on the show of his life.

Lifestyle

Don't miss out on the headlines from Lifestyle. Followed categories will be added to My News.

LOOK closely at Geoff Dyer’s recent paintings and you’ll notice an urgency in the swirls of colourful oil that dance across each canvas. The 72-year-old, recognised as one of Tasmania’s best known painters and one of Australia’s most respected and collected living landscape artists, has been working in his North Hobart studio in recent months with a new determination and purpose never before seen in the 40 years he’s worked as a full-time artist.

At Dyer’s most recent exhibition 18 months ago, a solo show of new oils and watercolours inspired by some of his favourite places in Tasmania, writer and friend Richard Flanagan told the crowded gallery about Dyer’s worrying health concerns.

Fast forward to the present day and Dyer continues to paint, albeit with a renewed sense of vigour.

Painting is what sustains him as he prepares for three major upcoming exhibitions — two in Tasmania and one in Sydney in December.

His worries are forgotten when he is in front of a canvas, intuitively moving paint around with his fingers, brush or pallet knife in his light-drenched loft where the floor is sticky with spilt paint and the air is tainted with the tang of turps and thinners.

“I paint from the shoulder, big paintings,” Dyer has previously said when describing his work. “I don’t paint necessarily in the manner of frenzied aggression, but it is very physical for me — the big canvasses, lots of physical exertion. It’s my exercise.”

The Archibald Prize winner may not be able to paint with the same stamina he once did, but long-time friend and Despard Gallery director Steven Joyce says for Dyer painting is life-affirming. “All Geoff wants to do is paint,’’ Joyce says.

“Geoff is happiest in his studio surrounded by a plethora of spent oil paint tubes, discarded rags and the remnants of his past endeavours. He doesn’t have the ability to reflect over six or seven hours, he’s got to do it in two to three hours.

“And sometimes that spontaneous work is better than when you’ve got time to ponder. It’s the end of Geoff’s painting power and you can see it — there’s an urgency there, it’s got an immediacy about it.’’

Joyce has known Dyer for 30 years and has represented him as an artist for the past 20. He has been instrumental in supporting his friend through this challenging time, while also helping bring to fruition two exhibitions to celebrate Dyer’s huge collection of work.

The Geoff Dyer: Portraits exhibition at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery opened on Thursday, bringing together a collection of famous faces painted by Dyer. It’s the first time the portraits have been publicly displayed in Tasmania and the only time they have been exhibited as a group.

Among them are environmental activist and former Greens leader Bob Brown, late Gallipoli veteran Alec Campbell, Mona founder David Walsh and author Richard Flanagan — a painting which won the prestigious Archibald Prize in 2003.

Dyer is only the second Tasmanian to receive the award in its 98-year history.

Visitors to the exhibition, which runs until October, will be able to use their smartphones to scan QR codes and listen to recordings of Dyer talking candidly about each painting, offering insight into his painting process as well as humorous titbits about the high-profile Tasmanians he paints.

Some of the audio has also been translated into text and included in the 52-page colour catalogue that will be available for sale as part of the TMAG exhibition and Despard Gallery’s Overview exhibition, which opens on Wednesday and features work completed by Dyer during the past year.

Joyce recorded the audio on his phone in recent months during chats with Dyer over a couple of red wines.

Even though he was familiar with many of the stories shared by his old friend, who he describes as a “larger-than-life character”, he still had a few chuckles listening to them being retold.

Joyce laughs as he recounts Dyer sending away former Tasmanian premier Paul Lennon when he arrived for a sitting, because he was wearing a check jacket, telling him “I don’t paint check”.

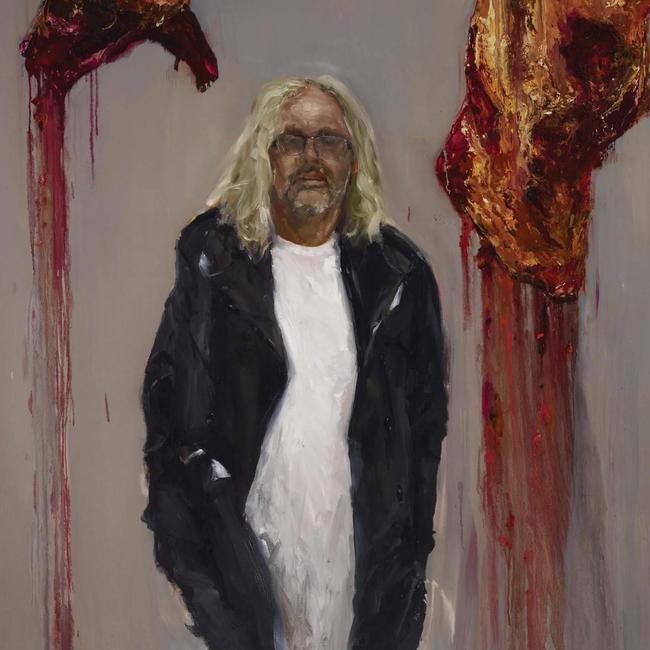

And Mona’s David Walsh sitting for Dyer for a second time and saying “you made me look like an axe murderer last year, what are you going to do with me this year?”.

“The stories are told in a very anecdotal style — there’s no art wank,’’ Joyce says with a grin.

One thing visitors to a Dyer exhibition always notice, he says, is the strong smell of paint in the air, as the multiple layers of oil are often still wet and take many months to dry.

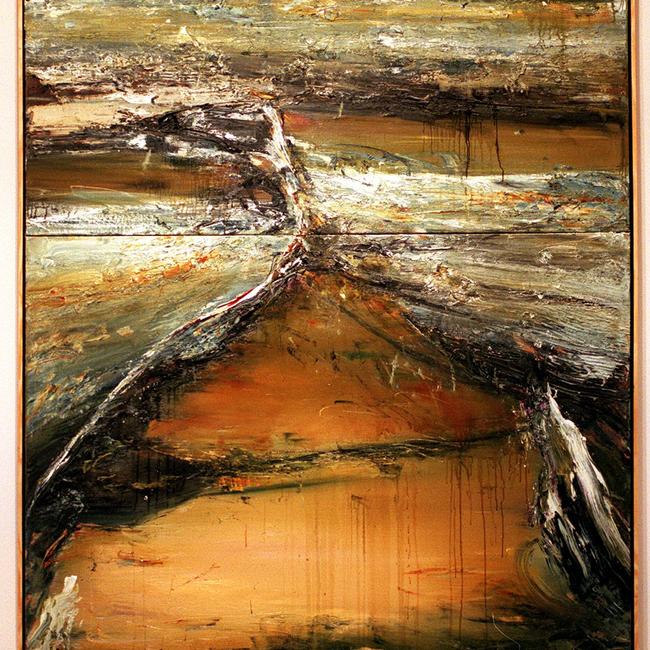

That will be even more true for this new landscape exhibition at Despard Gallery. “The landscapes and abstractions that make up Overview have been painted over the past year, and completed with a sense of urgency and determination,’’ Joyce explains of Dyer’s work.

“It is a great artistic achievement under difficult circumstances, and will no doubt endure as part of his artistic legacy.

“Both exhibitions demonstrate how Geoff’s paintings continue to increase in visual strength, cementing his standing as Tasmania’s greatest living artist.’’

Dyer first exhibited with Despard Gallery as part of the annual summer group show in 1999. Eleven solo shows later, Joyce says Dyer “continues to push himself creatively, his evocative oils resonating with a broad audience of both new and seasoned followers”.

His paintings fetch anywhere from $2950 to $85,000, but Joyce confesses he still tells Dyer if he doesn’t like one of his paintings. “I can tell him ‘that’s crap mate’ and get away with it,’’ he says.

Dyer is known for being hard on himself when it comes to his art, often threatening to paint over images he’s unhappy with, or discarding them to the corner of his studio until he can look at them another time. Responding to his fear of becoming a “recipe artist” — working to a formula and producing the same thing over and over — Dyer constantly shifts his style in subtle ways, always experimenting.

“Lots of artists are victims of their own success; they become subordinates to their own fashion,’’ Dyer told TasWeekend in 2016. “I don’t want that to happen to me.’’

He also credits some of his success to the subjects he paints, saying that “the sitter is as important as the painter”.

“I’ve had some wonderful sitters — I’ve been very lucky and it’s been a pleasure,” Dyer says. “But it’s not always easy. You know, a landscape won’t say, ‘Geoff, unfortunately I don’t look like that, I’m not happy with it’.

“Hopefully, you paint people with an aesthetic understanding that portraiture lies within the boundaries of this and that, without flattery and so on.

“I get asked a lot, but I don’t do commissioned portraits because, although you sort of get free rein, people are used to looking in a mirror and seeing themselves in a certain way, and that doesn’t necessarily match what I paint.”

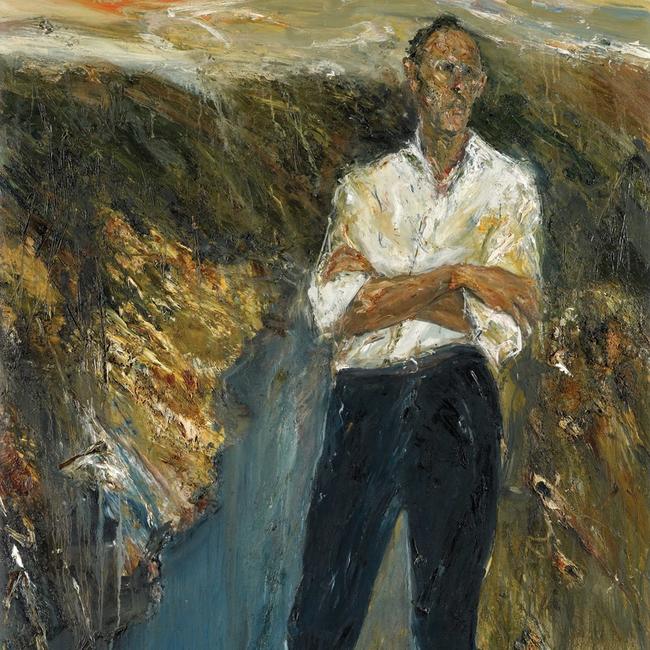

He says most of his early portraits were painted as small commissions for friends when he was teaching, and he rarely took them seriously. The first big portrait he painted was of Bob Brown for the Archibald Prize, which was a finalist in 1993.

Poet, playwright and Tasmanian aboriginal elder Jim Everett was painted by Dyer in 2008, and says Dyer has a unique way of looking inside the person sitting for him, giving portraits a “special touch of Dyer magic”.

“What I like most about Geoff’s paintings is that he has some sort of sixth sense for how a person should be pictured, using the brush and/or knife to bring out the soft, the hard, even the harsh side in a portrait painting,” he says.

Journalist and TasWeekend columnist Charles Wooley, who Dyer painted for the Archibald in 2017, believes “failure lies with the sitter, not the painter.’’

But despite feeling perhaps he was “too boring or not worthy enough” to have sat for Dyer, Wooley confesses he enjoyed the process.

“Who wouldn’t want to be painted by the luminary Dyer?’’, he says. “Of course, I enjoyed the process of sitting in his artistic midden of a studio as much as I think he enjoyed the act of painting.’’

TMAG director Janet Carding says there’s power in having so many images of high-profile people brought together in one room. “I enjoy imagining the conversations that might occur in the gallery when the lights are out,’’ she says.

“What might David Walsh, Bob Brown, Richard Flanagan, Margaret Scott, Alec Campbell, Robert Dessaix, Christopher Koch, John Clark, Jim Everett, Graeme Murphy and Paul Lennon have to say to each other?

“Not only is this exhibition a celebration of the work by a prominent Tasmanian artist, it is also about the lives and achievements of all those he has painted.’’

Dyer said three years ago that he wouldn’t be doing any more Archibalds. “I’m done,’’ he said at the time. “After I painted David Walsh [a finalist in 2011], I think that was the zenith of it for me. With that one, I couldn’t have done any better.

“Maybe something will happen in the future but I would have to be overwhelmed by the subject. I just can’t find a way to make a relevant statement through the figure [anymore]. I can do that with landscape though, I think.”

Dyer was born and raised in Tasmania, growing up in Moonah, where his father worked as a motor mechanic. He cannot remember a time he wasn’t interested in painting and drawing, doing his first oil painting when he was about eight — and he still has it.

Art took a back seat at high school, when he focused on maths and science. However, he soon rediscovered painting and studied at the Tasmanian School of Art in Hobart in the late 60s.

He began exhibiting soon after, balancing his time between working as a teacher, firstly on King Island, then UTAS’ Launceston School of Art and Burnie Technical College.

“King Island was one of the best years of my life,” Dyer recalls. “I was coaching the footy side and I did a few paintings while I was there. It was also where I painted a portrait of an old fellow who was 96 and had never left King Island.

“I never thought much about it at the time, but that was quite amazing. He would have been born on that island in 1870-something and he never ever left it.”

Dyer’s last teaching position, in the mid-70s, was at Elizabeth College (then Elizabeth Matriculation College), a stone’s throw from his studio today. He decided to quit and focus solely on making art.

“By that stage I was about 30, I knew it was now or never,” he says. “I needed to take that leap and be a painter. You need to do it at an age when you’re still stupid. Well, impetuous, maybe.”

He spent the next 20 years travelling regularly between Hobart, Melbourne and Sydney, building his reputation as well as his skills. He’s been working from his studio in North Hobart for the past 18 years, where everything from Pavarotti to Elvis Presley blares from the speakers.

Dyer’s work has been hung in the New South Wales Art Gallery more than 20 times — having repeatedly been a finalist in the Archibald Prize, the Wynne Prize (Australia’s most prestigious prize for landscape painting) and the Sulman Prize. He has exhibited extensively throughout Australia, as well as in Singapore, Guangdong and New York.

Dyer’s paintings are held in many private, public and corporate collections, including the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra, Artbank, University of Tasmania, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, and the Museum of Old and New Art. Despite his successes, Dyer admits there’s a strong element of chance to his art. “Sometimes it’s like going to the casino and playing the wrong numbers,” he says.

“You take a chance when you paint something. It’s about your ability to grasp the chance and use it. If, somehow, you are lucky enough to seize that chance and transmute it and the gods are with you, it’s good fun. If it doesn’t happen, then it’s not much fun at all.”

Dyer has been painting Tasmanian landscapes for more than 50 years, and is particularly drawn to the West Coast, where he likens his connection to Ocean Beach and the Henty Dunes to artist J.M.W. Turner’s enduring passion for London’s River Thames.

“When I was young, I visited the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery a lot, and you go to the things you can understand,” Dyer explains. “To me that was the colonial art room, which until recently was always the same every time I went.

“Those old dead brown and gold paintings of the past, that was the first intro I had to any kind of artwork outside my classes. I grew through all that, those traditions.

“I was doing some figurative work [portraiture] for a while but found myself drawn back to the landscape — sometimes abstract, sometimes derivative — but I find myself always surrounded by landscapes. I notice them. I can’t imagine painting cityscapes or being part of that figurative group, it’s not what I do.”

Unlike Turner, Dyer didn’t start out making neat, careful studies and wind his way into a form of elemental abstraction. Instead, he began as a painter of abstract works that gradually took on the lineaments of landscape.

“In Dyer’s case, it was a matter of recognising that his abstract works were inspired by the landscape and should not shirk from revealing that debt,’’ Sydney Morning Herald art critic John McDonald explains in the catalogue for Dyer’s latest exhibitions.

“At a time when abstraction has taken its place as one stylistic option among others, it makes little sense to pretend there is no tangible connection between the observable world and the imaginative world of the painting.”

Dyer is luckier than Turner, as his work is widely loved and respected. “Dyer is fortunate that contemporary audiences are willing to accept his expressionistic canvasses as legitimate landscapes,’’ McDonald says.

“In Turner’s day, the crowds queued up to mock his paintings. They claimed the artist was insane or suffering from some obscure eye disease. Even the greatest writers of the day found the works impossible to understand.’’

McDonald says Dyer expertly creates a sense of atmosphere in his work. “For Dyer, it’s the overall tone of a painting that’s important, whether it’s a hot, fiery scene such as the Tasmanian Summer pictures, or the chilly vistas of the King River series.

“When we look at one of these works, we immediately feel a sense of atmosphere. It’s only as we continue to look that we appreciate the finer points — the density of the forest, the translucency of the water.

“It would be a pointless exercise to ask Geoff Dyer why he painted King River or the South West Coast,’’ he adds. “It’s an instinctive choice.

“After a long bout of illness, Dyer says the first thing he wanted to do was to drive down to Cockle Creek and begin painting. Do these dense, glowering bush studies reflect his black mood or a sense of mortality?

“Most probably, but not in a way he would want to explain in words.’’

IN HIS OWN WORDS: GEOFF DYER ON SOME OF HIS SUBJECTS

The first portrait I painted for the Archibald. It was done fundamentally because I’d been in the Wynne and seen a lot of Archibald portraits and I thought, ‘gee, you know, it’s about time I probably had a bit of a go’. Bob’s an informal sort of bugger, and I wasn’t sure how was I going to paint him. He just came in wearing a white shirt and black pants, so that’s how I painted him. It’s almost as though he knows he’s going to be a statesman one day. The important thing about this portrait is not only Bob Brown, but also the landscape, which is based on a series of landscapes I did around the Reece Dam in Tasmania. The landscape becomes contradictory, strangely enough, because it is a dam. He seems to grow out of the landscape, like an organic force unto himself. I think it’s a good first painting.

When we met, he was in pretty good spirits, and at 105 he said, ‘good day, young man’, which made me at the age of 58 feel rather youthful. However, he was partially blind and I remember his eye being sort of distant from his head. I remember the art critic from The Australian at the time — I can’t remember his name — said he ‘liked it, but it was a bit messy’, which I thought was a bit odd. Because, sure it was a bit runny, but war is messy.

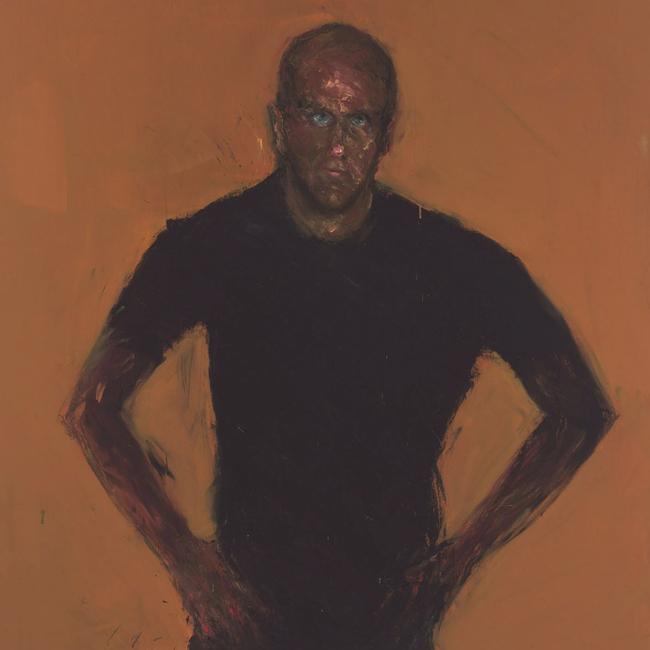

We knew each other, but not well. I distinctly remember that I’d asked Richard to sit, but he wasn’t too happy about it. Probably because he’d been painted three times, but never been hung, and I think he’d had enough. I think he took it all fairly lightheartedly, but I didn’t. So, I was a bit annoyed and I took it out on him fundamentally in the painting. So, what you see in the portrait is my mood, a kind of aggression — and feeling of discomfort, which is transferred into him. I spent the whole night with the painting in the studio, knowing that the eyes weren’t right. And in the morning, I made a correction. But I knew that it was a good painting and that it couldn’t be touched. And it just happened to win. It was as simple as that.

In 2010 I did a portrait of David Walsh and it was a good portrait. And it wasn’t hung. And, like all failed aspirants, you’re a little bit upset. But he allowed me to have a crack at him again. He said ‘well, you made me look like an axe murderer last year, what are you going to do with me this year?’ So I photographed him at Mona. I went back to the studio and I sort of thought ‘well, how am I going to paint this bloke?’ I was out at Mona one morning on my own and saw the meat hanging. And I thought well, meat, fantastic, I love meat, I’ve never painted meat — but Rembrandt did. Then I just eased myself in to it.

Paul came to the studio and I didn’t know what to expect. He came slightly as though he had a perm, like he’d gone to the hairdressers and had his hair blow dried or something. He had a check jacket on, and I said ‘well, Paul, I don’t paint check jackets’, so let’s do a couple of drawings and come back next week, and he did. I painted in front of him a little bit, he must have been horrified, really. And he left. And I battle around with this painting. So what you have is what you’ve got. He’s a big, stocky, bullish sort of character — broad shouldered, almost exaggeratingly broad shouldered — and here’s our premier. He’s the only one of these portraits that was outside the Archibald context.

Geoff Dyer: Portraits is now on at the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery (until October 6), bringing together a collection of paintings of high-profile Tasmanians in Tasmania for the first time. tmag.tas.gov.au

Overview, a collection of Dyer’s new work, opens at Despard Gallery (Castray Esplanade, Hobart) on Wednesday, July 31, at 5.30pm and runs until August 25.

despard-gallery.com.au