Opinion: Does Netflix’s Adolescence help or hinder the push to combat violence against women? For and against

The smash-hit drama Adolescence has sparked heated debate about the toxic online “manosphere”, incel culture, gender roles and loneliness. Two experts debate whether the series helps or hinders efforts to address violence against women.

Opinion

Don't miss out on the headlines from Opinion. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The gripping crime drama Adolescence has been Netflix’s smash hit of 2025.

The four-part miniseries, staring Stephen Graham, Owen Cooper and Ashley Walters, tells the story of a 13-year-old boy who is arrested for the stabbing murder of his female classmate.

It has sparked heated debate about the toxic online ‘manosphere’, incel culture, loneliness and the gender roles.

Neuroscientist Selena Bartlett and anti-violence campaigner Phil Cleary share their views — one for, one against — about whether the series helps or hinders the efforts to address violence against women.

A gut-wrenching and much-needed wake-up call: Selena Bartlett

Netflix’s new film Adolescence has left audiences stunned and shaken, and rightly so.

It’s a gut-wrenching story about how toxic online communities can manipulate and brainwash vulnerable young people, drawing them into a dark world of isolation, resentment, and violence.

At the heart of the story is a young man pulled into the incel belief system, which is a movement rooted in bitterness towards women and society, driven by an inability to form romantic relationships.

British Prime Minister Keir Starmer was so moved by Adolescence he backed a parliamentary push to screen it in schools.

But Adolescence is more than just a film — it’s a wake-up call for parents, teachers, and communities everywhere.

It shows how online toxicity and family issues can affect young people’s minds.

Instead of blaming parents, schools, or kids, we should ask how our communities became places where young people feel lost and disconnected.

Social media and online gaming are designed to keep people hooked.

Kids spend hours online, which takes away from their real-world connections.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics found 40 per cent of kids spend 10-19 hours on screens weekly.

When young people feel ignored or misunderstood in real life, they are more likely to turn to online communities that make them feel accepted, even if they promote harmful ideas.

Social media algorithms, designed to keep users engaged, often push them into echo chambers where harmful beliefs strengthen.

Incel groups thrive in these spaces, using vulnerability and loneliness to recruit new members.

But this problem isn’t just about social media.

It’s also about how trauma and stress get passed down through families.

Without realising it, families pass on patterns of disconnection to their kids.

One powerful scene in Adolescence happens at a school, and it feels all too real.

The film exposes how the education system is failing teachers and students, overwhelmed by impossible demands and dwindling resources; teachers are stretched thin, juggling curriculum demands while acting as counsellors and mentors, leaving them burnt out and powerless.

Meanwhile, students are caught in a storm of stress and trauma, lashing out with disrespect or burying themselves in their phones because they have no other way to cope.

Teachers are burning out and leaving the profession because they are overwhelmed by trying to help students whose lives are chaotic outside of school.

According to the Teaching and Learning International Survey, bullying or intimidation between students happens at least once a week.

Australian teachers also reported feeling less prepared to handle bad behaviour than teachers in other countries.

Schools are supposed to be safe places where kids feel valued and supported, but instead, they have become stressful and chaotic.

While Adolescence serves as a warning, the documentary SEEN acts by offering real solutions and hope.

Touring Australian cinemas, SEEN challenges outdated ideas about parenting and trauma, blending raw personal stories with cutting-edge neuroscience to show how building real connections protects kids from falling into dark online worlds.

The main message is simple yet powerful: 20 minutes of genuine connection with a child each day can rewire their brain and build resilience.

Kids today are navigating a world full of challenges, carrying stress and trauma that often go unnoticed.

Before they even step into the classroom, many are already feeling overwhelmed.

Instead of blaming teachers, parents, or kids, let’s come together as a community to build a culture of care and connection.

When natural disasters hit, people come together to help each other.

We can’t afford to let kids face the online world alone.

To support them, we must step up as parents, teachers, mentors, and community members.

It’s time to focus on building stronger, more connected communities.

It’s not just up to parents and teachers; everyone, including tech companies and policymakers, has a role.

Our kids deserve a future where they feel protected, valued, and truly connected to the real world.

Let’s make sure they feel seen because when we see our kids, we change their world.

Professor Selena Bartlett is a neuroscientist at the Queensland University of Technology, the author of Being SEEN, features in parenting documentary SEEN, and the host of the Thriving Minds podcast.

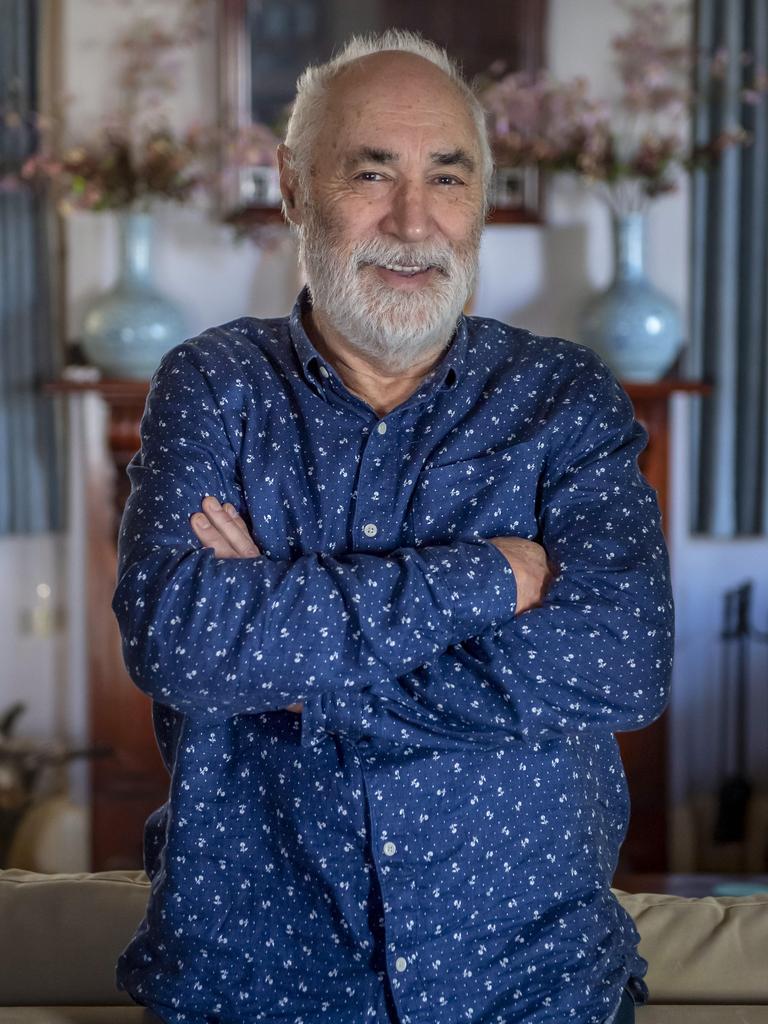

Adolescence raises serious questions but misses mark: Phil Cleary

This past week we’ve been glued to Netflix watching a 13-year-old working-class English boy stab his schoolmate, Katie, to death in the much-lauded four-part series, Adolescence.

Thankfully, as I discovered when trawling the internet, there are on average less than five killings a year in the UK by children under 14 years of age.

Given the worldwide war on women – claiming more than one woman every three days in the UK – I’m left wondering why writers Jack Thorne and Stephen Graham chose a 13-year-old boy to be their killer ”man”.

This question wasn’t on the lips of the online theorists heaping praise on the writers, the gritty social realism that underpinned the storytelling, and the questions the series raised about social media’s role in producing a 13-year-old murderer.

That Adolescence went so far as to portray misogynist podcaster Andrew Tate as a major threat to the relationship between boys and girls only won more praise from viewers.

Adolescence does raise some serious questions about men and violence.

Was 13-year-old Jamie a casual victim of a father who considered macho activities like boxing and football more important than books and sensitive fatherly guidance?

Was Jamie’s rough around the edges, clumsy father blind to social media’s place in his son’s progress through life?

Nevertheless, even if the answer is yes, does anyone genuinely believe the father’s failings would be sufficient to turn his son, and any other boy for that matter, into a woman hater and a killer?

If not, is it really Andrew Tate who must take the blame?

Is Tate’s propaganda so beguiling that all a girl has to do is say “I’m not interested in you” to transform a 13-year-old suitor into a woman killer?

The irony here is that virtually every adult woman who dies at the hands of a man known to her is “murdered” because, like 13-year-old Katie, she has said “no” to a relationship with her killer.

Ending a relationship is one of the most dangerous things a woman can do.

The problem in Adolescence is that in taking some of the elements of the misogyny that drives adult “woman killers” and transferring them to a 13-year-old boy, the writers created a fiction that audiences are treating as normality.

Researching the killing of women after the murder of my sister Vicki in 1987, I was left in no doubt as to the complicity of society in the violence stalking women.

There was no internet or Andrew Tate when a newspaper ran the headline “Love pulls Trigger” above the story of a man who’d shot a woman – his former partner – in front of her two children in 1987.

“Despair prompts killing” hardly captured the horror of a father murdering his ex-wife’s two young children in a house fire.

Nor did “Dream Marriage Ends in Death” and “Death on a Sunday Morning” have readers thinking a woman had been strangled to death.

The misogynist narrative of the 1980s didn’t need Andrew Tate’s inflammatory words.

The newspaper headline in February 1989, “Kill case man’s love plea”, in the aftermath of the unsworn evidence of the man who attacked and murdered our sister outside her place of work was just more of the same.

These were the days when juries – without access to online misogynist warriors – were punishing dead women with obscene not guilty verdicts that transformed killer men into victims and women into provocateurs.

The verdicts and the pillorying of women in the media blithely rolled on without a word of dissent from politicians, law makers and media moguls until we campaigners stormed the patriarchal barricades.

Given the history of the killing of women — and the victim-blaming that has, and too often continues to sanitise the killings — we do need to be asking questions about why men kill.

The problem is that Adolescence doesn’t ask those questions and the real facts are that the killing of a 13-year-old girl by a boy her age is as rare as hen’s teeth.

What’s more common is the abuse, sexual assault and killing of girls this age by older men, some of whom are their fathers.

Rather than a torrent of theorising on social media about the rarest form of ‘woman killing’, we need to be talking about men’s violence against women.

The closest Adolescence gets to asking this question is in the harrowing scene in which a psychologist interviews Jamie.

What emerges is the haunting proposition that, like every other woman killer, young Jamie took Katie’s life because she didn’t want to be with him.

In his words she was a “bullying bitch”, who’d “cruelly” disparaged him.

Although the psychologist talked to the boy about murder, she never asked him whether he knew that every year in the UK around 120 women were killed for the same reasons, he’d killed, or as he said, ‘should have killed’ Katie.

Nor did the psychologist ask the boy whether he’d heard of the #MeToo movement or believed girls should have the same rights as boys.

Given his mental agility in the interview, he was more than capable of answering such questions.

So, while pondering whether Adolescence is a the Netflix classic everyone should be watching, I’d suggest we lobby for a version of the series in which the killer is an estranged husband.

While doing that we should ask why Jamie’s parents, and his sister, were depicted as victims while the dead girl’s parents weren’t seen or heard from.

Was the real victim the 13-year-old killer?

Phil Cleary is a Melbourne anti-violence campaigner. His sister, Vicki, was murdered in 1987 by her ex-partner.

This year’s “Vicki Cleary – End Men’s Violence Against Women – Day” will be held on May 4 at the Coburg Football Ground. This game between Coburg and Carlton’s VFL team starts at 1.05pm, with a moment’s silence at 12.50pm.

Originally published as Opinion: Does Netflix’s Adolescence help or hinder the push to combat violence against women? For and against