Wojtek the bear went to war and won hearts across the world

Perhaps the world needs more warriors today like the bear who helped topple Nazism, one of the lesser-told stories of World War II.

Since the 16th century the Muscovite state has had many names – Rossiya, the Tsardom of Russia, the Russian Empire, the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian Federation – but all of them have been depicted as the Russian Bear.

A big, brutal, blundering and untrustworthy bear – its accurate and enduring emblem. Some of its oblasts (administrative regions) still boast them on their coats of arms.

Bears are best avoided, and Vladimir Putin’s version today is more dangerous than at any time since Germans tore down the Berlin Wall. With brave Ukraine’s future uncertain as it slowly but inevitably cedes territory to its enemy, there remains the possibility that Russia could crush it or reach a “peace” deal that renders it a tamed client state.

That would be a tragedy for the Ukrainians and the world, particularly Europe. It would put the Kremlin’s tanks not only on the borders of Norway, Finland, Estonia and Latvia but also right at Poland’s door.

The Chief of the General Staff of the Polish Armed Forces, General Wieslaw Kukula, put it bluntly recently while talking to the latest intake of cadets: “Everything points to the fact that we are the generation that will stand with arms in hand in defence of our country – we have to build an armed force prepared for this type of action.”

Perhaps Kukula should scout around the Bialowieza Forest for a few recruits – you know, bears. One of the lesser-told stories of World War II is the conscription of Wojtek the bear, whose unflinching bravery and epic work ethic helped Polish forces as they tamed fascism on the Italian peninsula.

Wojtek began his working career as a civilian helper, was made a private in the Polish Army and eventually was elevated to corporal. He survived the war and, 80 years ago this year, was retired to a zoo in Scotland where he lived out his days until December 1963.

He had lived 21 years. Action-packed barely begins to describe them all. The animal that would be named Wojtek – which translates as “happy warrior” – was born somewhere around Hamedan, 320km southwest of Tehran.

Wojtek would have been born, perhaps as a single, to a Syrian brown bear mother that would have been fiercely protective of him. It is assumed she was shot by hunters – so many were then. There are few left today (and none in Syria).

In April 1942, a young Iranian boy emerged from the hilly forests of Hamedan with a violently wriggling sack. He approached some Polish soldiers who were slowly making their way to Italy for some of the final battles of World War II. The boy spoke only Farsi, the men only Polish.

How the Polish soldiers came to be there that day is an extraordinary story itself. The men were part of Anders’ Army, a ragtag collection of formerly imprisoned Poles loosely formed under the direction of World War I hero Wladyslaw Albert Anders.

His force – officially called the Polish Armed Forces in the East – was made up of men liberated from prison camps in Russia. Anders himself had been detained in Moscow’s feared Lubyanka prison. The men had been taken there after the joint invasion, occupation and partition of Poland by Germany and Russia in 1939. But when Adolf Hitler ratted on his pact with Joseph Stalin in June 1941, the Russians freed tens of thousands of captives, although they had murdered many men of fighting age and with military experience.

Anders’ Army comprised three divisions of 25,000 soldiers, including a then unknown 29-year-old Menachem Begin, later to be the Nobel Peace Prize-winning prime minister of Israel. The troops travelled by ship across the Caspian Sea to northern Tehran before making their way by train to Britain’s Palestine Mandate, overland to Egypt and then by ship to Italy.

It was while waiting for Anders’ colleagues that some adventurous Polish soldiers – probably in search of food supplies because their rations were so thin – made their way to the hills and encountered the boy and his bag.

The cub that would become the legendary Wojtek stuck his head out and wrestled to be free. Stories differ as to what the soldiers swapped to buy the bear and it is often reported they gave the boy tins of bully beef. That’s unlikely because these men were still being supplied from Russia, which was stingy with food for the Poles who had recently been its prisoners. But the troops did have black bread, biscuits and powdered condensed milk.

The boy agreed to the trade and the bear was quickly named and recruited to raise the spirits of the some of the war’s bravest men. He would copy everything the men did: walk upright, stand under a shower, have a morning coffee, play-wrestle, drink beer and even sit with them to “smoke” – well, eat cigarettes he was given, a habit that lasted the rest of his life. Like them Wojtek was fearless.

He ate what the men were sent as rations: condensed milk (fed to him from a vodka bottle), honey, crackers and as often as they received any, fresh meat. It was quite a sacrifice; Wojtek would grow to more than 180kg and the men’s rations were infamously meagre. But the company fell in love with their bear. Then someone came up with the idea of adding him to the list of soldiers as a private – he’d be sent his own rations. By this time he was marching upright with the company and was even taught to salute

Anders’ men travelled to Egypt for their final training before entering the southern theatre of war in Europe. The Poles found the heat oppressive, as did Wojtek. One hot morning he went to the shower yard, from which high-pitched screams were heard. An Arab had been hiding there and Wojtek always took an interest in strangers.

Soldiers from other countries would look on bewildered as the Poles tramped by with a tall bear not quite in step with them. By the end of the year Anders’ men sailed to Naples to march into battle.

There was no way that bear was going to be left behind. He saw the soldiers as his parents. It had been Lieutenant Anatol Tarnowiecki’s idea to keep Wojtek – he could see how he lifted the company’s spirits.

At the Port of Naples, one of Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery’s lieutenants, Archibald Brown, checked off the names of the arriving troops. He read out “Private Wojtek” and the bear’s Polish friends burst out laughing.

By the end of 1943 the Allied troops from Egypt were part of the slow, bloody battle through the spine of Italy and towards Rome.

The key encounter for these troops – who came from South Africa, India, Canada, the US, Britain and, of course, Australia – was the Battle of Monte Cassino. On top of a steep, rocky hill 80km south of Rome sat the Monte Cassino abbey, founded in 529.

Starting on January 19, 1943, the Allies – 240,000 men, almost 2000 tanks and assisted by 4000 planes – began the attack, which lasted 122 days. As always, the Poles were in the thick of it.

When Wojtek saw a pair of men carrying 45kg boxes of British-made 25-pounder shells up the hill, he joined in lugging boxes on his own to the gunners above. He had long become used to the sounds of bullet fire and rockets. The Battle of Monte Cassino cost the lives of 50,000 men, 4199 of them Polish.

The Poles fought on to Bologna and were there on May 8, 1945, when victory in Europe was declared. The soldiers had mixed feelings about what was to come after the war. Their country had been betrayed at the Yalta Conference where three leaders – Britain’s Winston Churchill, Russia’s Stalin and US president Franklin D. Roosevelt – divided Europe and placed Poland in the Soviet sphere, where it would remain cruelly trapped for 44 years.

Anders’ men were not demobbed for some time. Many stayed and married Italian girls. A few went home, including Tarnowiecki, whose wife had died and whose three children were effectively orphaned. They were reunited after 10 years and he settled in Cieplice near the Czech border, where he died in 1991.

Nobody wanted to send Wojtek to Poland. He was demobbed – now elevated to corporal – to a British military camp in Berwick-on-Tweed, about 75km from Edinburgh, where he lived in the barracks, sleeping in a wooden crate built for his 200cm frame. He occasionally swam in the Tweed River, taken there by the Poles who had moved to Britain. The men were still on rations, but locals helped with food for Wojtek, including thousands of apples.

As the Polish fighters learned English and slowly integrated into British civilian life – and some came to Australia – it was decided that it would be best for Wojtek to live out his years at the Edinburgh Zoo. On Saturday, November 15, 1947, his handler, Lance Corporal Peter Prendys, led his bear to the back of a truck and joined him on the trip to Edinburgh.

For years he was a star attraction, but he gradually became withdrawn and in the colder months may have become unsettled by an urge to hibernate, as Syrian bears will in higher altitudes.

Prendys left Wojtek with some blankets and clothing with familiar smells. Prendys never recovered from the stress of abandoning his friend and would become tearful when asked about him. He died in London in 1968.

Thoughtful zoo staff who worked with Wojtek bought old Polish uniforms and wore them around him and even learned some Polish words such as “Hello”.

From time to time some of Wojtek’s old military mates would visit the zoo and he sometimes recognised them before they called out to him. Wojtek would wave. It was reported that zoo staff bent the rules to allow these men to throw Wojtek cigarettes, which he ate heartily.

One former soldier who served with Wojtek went to visit him and recalled: “As soon as I called his name, he would sit on his backside and shake his head, wanting a cigarette.”

Wojtek died at the zoo on December 2, 1963.

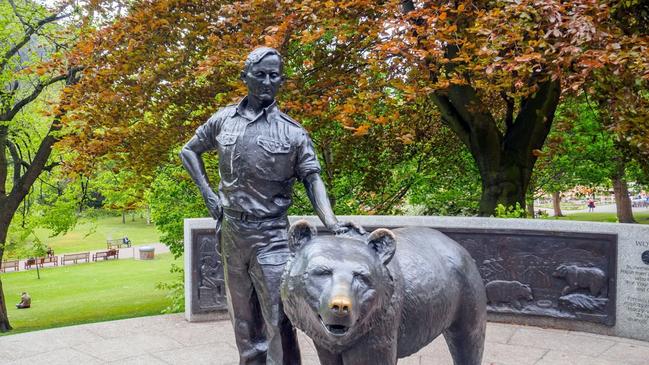

There is a statue of Wojtek in Edinburgh, another near Berwick-on-Tweed and in Cassino in Italy. Polish and Italian streets are named after him. A book for children, The Bear Who Went to War, was recently turned into a play, and a road leading to Poland’s Poznan New Zoo is named Corporal Wojtek Street.

Wojtek’s old company adopted an image of him carrying a shell as their insignia, which they use to this day.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout