Poland has been warning about Russia for years but West didn’t listen

Poland, now a central plank of Europe’s conflict with Russia, was warning about its neighbour’s intentions long before the invasion of Ukraine.

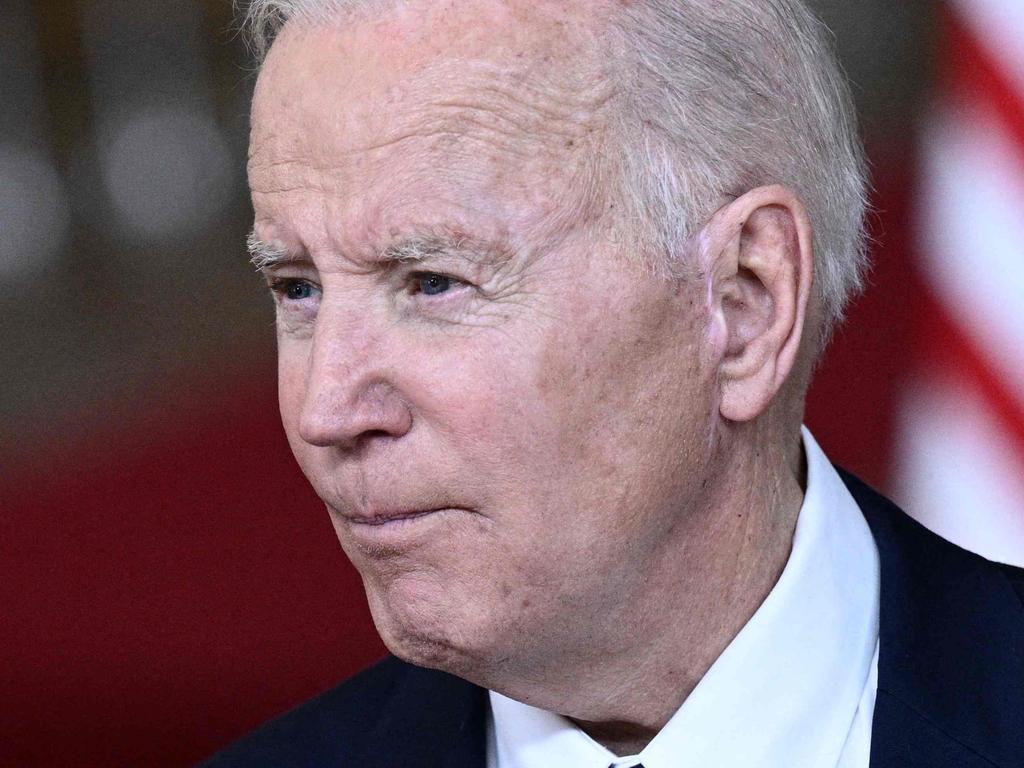

When Joe Biden landed in Poland on Friday, he arrived in a country that has become a central player in Europe’s conflict with Russia.

More than two million Ukrainians have fled to Poland since the Russian invasion began a month ago.

Arms shipments from the West are largely sent into Ukraine through Poland, and injured Ukrainian soldiers are evacuated to Polish hospitals.

After warning about Russian imperial ambitions for more than a decade, Poland is now in a position to play a pivotal role in shaping the NATO defence policy and the West’s response to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Already, several allies – including those that had previously waved away Poland’s security concerns – are taking steps that the country has been pushing for years: imposing tougher sanctions against Russia, increasing military spending and advocating a larger military presence at the eastern edge of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation.

“Poland’s role is absolutely critical,” said Paweł Szrot, head of the chancellery of Polish President Andrzej Duda.

“It is very sad that the war and Russian aggression was necessary for Europe and the world to admit that Poland was right.”

Mr Szrot said he expected Mr Duda and the US President to discuss strengthening NATO defences, as well as help for Poland in dealing with the refugee crisis.

“Real strengthening of the eastern NATO flank,” Mr Szrot said, outlining Polish hopes for the meeting. “New forces. New equipment.”

Until the invasion of Ukraine began, Mr. Szrot’s nationalist party, Law and Justice – which has taken steps to undermine the independence of the country’s courts – was seen by some Western allies as an unreliable partner.

On the campaign trail in 2020, Mr Biden listed Poland alongside Belarus and Hungary in “the rise of totalitarian regimes in the world”.

But the war has led Poland to recalibrate its relationship with the West.

Now there is wide agreement within NATO to send the reinforcements that Poland is requesting.

Concerns about the country’s court system and its rule of law, which had roiled Poland’s relationship with other EU countries, haven’t been an obstacle.

The past few weeks have been humbling for western Europeans, who have been forced to acknowledge that their view of Russia was misguided, while the former Soviet bloc countries saw the situation more clearly, Elisabeth Braw, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, said.

In particular, Germany pursued a policy of “change through trade,” hoping that new energy deals with Moscow would help export liberal values into Russia, brushing off complaints from Poland that Europe was becoming too dependent on gas from a hostile government.

“Now we can see that these people we’ve looked down on for so long actually know a thing or two,” Ms Braw said.

For Poland and other central European nations, wariness is born of a history of fighting Russian incursions that goes back hundreds of years.

Tsarist Russia annexed parts of Poland in the 1790s. Poland only regained full independence after World War I, then swiftly faced an invading Bolshevik army it managed to repulse, halting the westward spread of the revolution.

The Soviet Union, working with Nazi Germany, invaded the country during World War II and imposed communist rule after 1945.

Poland was Europe’s first country to leave, after it held democratic elections in 1989, accelerating a wave of social movements that led to the fall of the Soviet Union.

At the time, Poland was roughly as poor as Ukraine, in per capita gross domestic product terms. But while Ukraine languished in Russia’s orbit, Poland jolted westward, let state-owned companies fail, joined NATO in 1999 and the EU in 2004, earning the freedom to trade and travel across the continent.

Its per capita GDP is now four times as large as Ukraine’s.

Poland has become the model for what Ukraine’s pro-European majority believe their country could achieve if welcomed into the EU.

Once inside the bloc, Poland became the loudest voice arguing that post-communist Russia continued to pose a threat to eastern European nations – especially to Ukraine, whose NATO membership aspirations Poland backed. The way to confront Russia, successive Polish governments argued, was with US-backed military strength, not with economic engagement.

During Russia’s invasion of Georgia in 2008, the president of Poland travelled with the leaders of Ukraine, Lithuania and Latvia to the country’s capital, where he warned Western allies about Russian aggression.

“Today Georgia, tomorrow Ukraine, the day after tomorrow – the Baltic States and later, perhaps, time will come for my country, Poland,” Lech Kaczynski, then the Polish president, said in his speech.

“We are here to make sure the world makes an even more powerful response, including, in particular, the European Union and NATO.”

At the time, many allies waved his concerns away as outdated Cold War thinking.

Barack Obama cancelled a planned missile shield in Poland the next year during his effort to reset relations with Mr Putin.

The Russian President managed to turn central European leaders who had once been anti-communist dissidents – Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban and Czech President Milos Zeman – into political allies.

Germany opened a pipeline to bring in Russian gas in 2011 and agreed to build a second pipeline, over Polish and Ukrainian objections, in 2015. Former German chancellor Angela Merkel crafted sanctions, following the annexation of Crimea, that eastern countries criticised as too soft.

Though NATO’s posture began to shift after the invasion of Crimea in 2014, Polish officials have continued to complain that there aren’t sufficient NATO troops in the country.

“I participated in so many meetings where the Polish side was telling German politicians, ‘You cannot be so naive … Russia is a threat you have to watch out for’,” said Adam Traczyk, an associate fellow at the German Council on Foreign Relations, who studies the German-Polish relationship.

As a result, Mr Traczyk said, Polish leaders now believe they have the high ground in their relationship with western Europe: “Poland was right and Germany was wrong.”

Germany is doing an about-face on Russia, pledging $US100bn ($133bn) in new military spending and beginning to look at how to wean itself off Russian oil.

Poland, meanwhile, is trying to establish itself as a leader in the defence of eastern Europe.

Dissidents from the neighbouring dictatorship of Belarus are welcomed. Immigrants from Georgia, after Russia’s 2008 invasion, built a large community in Warsaw. Last week, Polish officials visited Kyiv, where they called for a NATO peacekeeping mission to Ukraine – a step most of the alliance isn’t prepared to take.

The attitude toward Ukrainian refugees is a reversal from 2015, when Poland refused to take in refugees from Syria, while Germany absorbed more than a million. Since 2015, when the Law and Justice party won a majority in parliament, Poland has embraced a number of policies that much of the West views as illiberal and undemocratic.

The party has drawn criticism from the West for attempts to cement control over the country’s media and for its stand against LGBT rights. The government has also moved to limit judicial independence, and the country’s top court has since ruled that some EU laws may not apply in Poland.

In response, Brussels has linked disbursement of EU funds to the rule of law. During this week’s parliamentary session, the government will discuss bills aimed at restoring the independence of the judiciary system.

“This is a pivotal moment for Poland,” said Max Bergmann, a senior fellow at the Centre for American Progress. “Poland can say, ‘We need to focus on Russia, because it’s a threat to democracy in Ukraine.’ But they can’t stand up to Russia and then undermine democracy at home. I think that will be a big part of President Biden’s message when he comes.”

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout