Why the notion of a double life has such a hold on British culture

The popularity of a recent BBC reality TV show highlights a long affair with double agents and natural aptitude for deception.

In the final episode of BBC reality TV show The Traitors, one of the last surviving contestants declares she has made “friends for life” while filming this strange and utterly compelling slice of television.

For 12 days, in a damp Scottish castle, the participants have been deceiving and scheming against each other to try to establish, for a large cash prize, which of them are traitors and which are “faithful”. In this absurd artificial situation, they grow increasingly close.

“I don’t think anyone can fake those kinds of relationships and those bonds,” declares the survivor quoted above. She is quite wrong. An ability to simulate friendship lies at the heart of all great treacheries.

The most successful traitors have tended to share a set of traits: charm, a cold heart, strategic thinking, self-belief, narcissism. But above all, treachery is about forming friendships and then betraying them, while enjoying the psychological supremacy this lends.

Infidelity is a drug, and so is secrecy. As the program unfolds, we witness the traitors growing higher and higher on the ruthless exercise of private power, the essence of all spying.

There is a reason why The Traitors has proven such a hit in Britain.

The notion of the double life holds a particular grip on British culture, the story of the individual who appears to be one sort of person from the outside, but is someone utterly different within. That is why Britain has produced so many successful spies, and so many novelists who have previously been spies, from Graham Greene to Ian Fleming to John le Carre.

Britons have a natural aptitude for deception. The French perceive us as “perfidious Albion” with good cause.

Perhaps it reflects an innate culture of theatricality, but for many there is a particular satisfaction in waiting for the 97 bus while believing you know a little more than the person standing next to you. Dutch people do not think this way. Nor do Africans.

Kim Philby was the greatest traitor in British history, a KGB spy who betrayed MI6 from within for decades.

He had charm in buckets, a lethal ability to draw people into a warm embrace that blinded them to his true nature. He was funny, generous, interesting, and wholly ruthless in manipulating those around him. He had what Greene once described as “a splinter of ice in the heart”, essential for spies as well as writers.

Long after Philby’s double life was revealed and he escaped to Moscow, his friends continued to adore him: the friendships outlasted the treachery they had enabled.

“Befriend and betray,” the most successful of the TV traitors declares, working through the rest of the cast, befriending, killing and banishing allies, innocents and enemies alike.

The contestants who seem to display insufficient friendliness are ejected first: the quiet ones, the socially awkward, the loners – all of them faithful. The last recruited traitor does not survive long, lacking the talent for friendship. Meanwhile the arch-traitor remains undetected, protected by a carapace of ebullient, slightly scatty charm.

As in the case of Philby (and Anthony Blunt, his fellow spy inside the British establishment), whenever suspicion gathers in the castle, friends rally round: the TV traitor is just too charming to be false.

And when this betrayer is finally revealed, those who have been deceived and lied to still love the imposter.

There is an old acronym used by the intelligence services to describe the motivation of the spy or double agent: MICE, standing for Money, Ideology, Coercion and Ego. Of these, by far the most important is ego; every successful traitor and betrayer, for good cause or bad, is compelled by hubris.

The contestants cannot disguise the thrill that comes from being selected as a traitor, and the opportunity to join a covert cell. As Philby described his recruitment in 1933 by Soviet intelligence: “You do not hesitate to join an elite force.” He revelled in his membership of the most secret club, just like the televised traitors.

As in the TV series, real traitors must be prepared to betray each other. Guy Burgess, one of the so-called Cambridge spies, knew he was exposing Philby by fleeing to Russia in 1951; when Philby was finally cornered he was prepared, in the parlance of the program, to throw Blunt “under the bus”.

But there is a price for treachery that goes beyond the obvious risk of getting caught. Telling one lie is easy. Telling multiple, compound lies is exhausting, stressful and very difficult, as each falsehood builds on the one preceding it. Successful traitors tend to have exceptional powers of recall.

Betrayal is emotionally draining. The traitors visibly wonder who and what they have become under the weight of duplicity. The tears wept by each exposed TV traitor are not crocodile: they are weeping from sheer relief.

As the television game progresses, the intake of alcohol by the traitors appears to increase. “Oh thank God, prosecco !” declares one after a particularly draining round of deception and pretence. In the real world, alcohol allows the traitor to enter a parallel chemical reality, as distinct from the false reality they must live when sober. For some, it is actually easier to lie well when slightly pickled.

Four of the Cambridge Five became alcoholics. Philby never expressed a word of remorse for the hundreds, perhaps thousands, he had sent to their deaths, but he ended up sodden with vodka in his Moscow exile.

“They were quite as ready as I was to contemplate bloodshed,” he declared of those he killed, which is precisely how the TV traitors justify their actions.

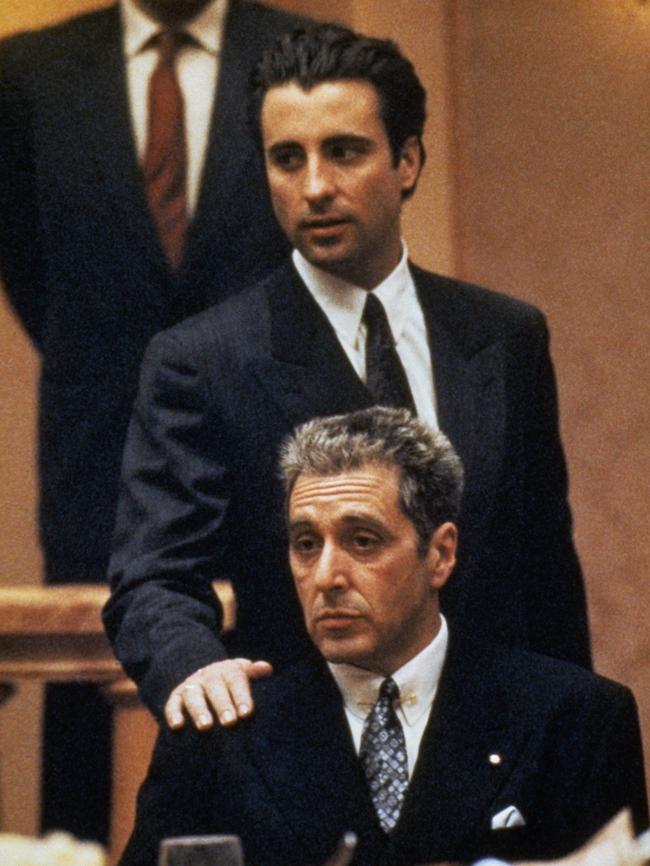

“Keep your friends close, but your enemies closer,” declares Michael Corleone in The Godfather Part II.

In the claustrophobia of the castle, as in real-life treachery, that dictum is reversed: the friends you keep closest are most likely to be your enemies.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout