Why lack of sleep is so bad for you

Poor sleep in middle age may cause heart disease and dementia, studies show. Here’s what you can do.

For everyone who has managed to get more sleep during the pandemic (no commute equals a longer sleep-in) there are those who are getting even less.

Then there are the people who go to sleep easily only to wake in the early hours, and others who spend a fitful night. If you fall into one of these sleepless categories, two new studies will prove alarming as they outline yet more reasons that a long, deep slumber is essential for health.

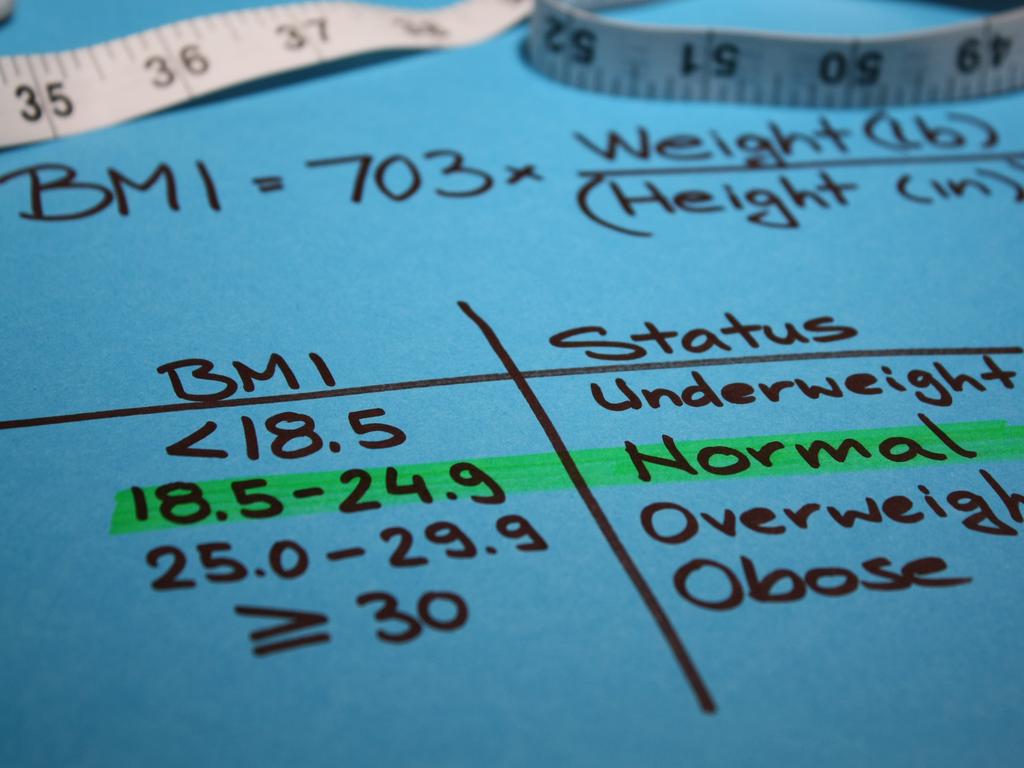

In the first of the published papers, Dr Severine Sabia and a team from University College London and the French national research institute Inserm tracked the health and lifestyle habits of more than 7959 people, all of whom self-reported their sleep patterns for about 25 years, starting when they were aged 50.

In findings published in the journal Nature Communications, Sabia showed that people who regularly reported sleeping six hours or less on a weeknight were 30 per cent more likely to be diagnosed with dementia than “normal sleepers” (who got at least seven hours) after three decades.

In a double blow to poor sleepers, researchers from Maastricht University medical school then reported that longer periods of fitful or fragmented asleep — for which you can blame a crying baby, snoring partner or barking dog — led to nearly double the risk of dying from heart disease for women, compared with the general population. While the link was less evident in men, there was still an associated risk.

“Typically people will feel exhausted and tired in the morning because of their sleep fragmentation,” says Dominik Linz, an associate professor at Maastricht University who led the study.

But how do you know if your sleep patterns are cause for concern and what, if anything, can you do?

Don’t get stressed about fragmented sleep

Fitful or fragmented sleep, dubbed “arousal burden” by the Maastricht researchers, is a normal part of our sleep patterns. “We all experience it to some degree,” says Dr Neil Stanley, a former director of sleep research at the University of Surrey and the author of How to Sleep Well.

“We have many different arousals during the night because, from an evolutionary perspective, it would be unsafe to remain unconscious for seven or eight hours and we are primed to respond to threat from a noise.”

Anything from traffic noise to children, fidgeting partners to sleep apnoea and breathing problems can disrupt our sleep.

“Sleep needs to be fragmented for at least 90 seconds for us to perceive that we are awake,” Stanley says.

Over time we become accustomed to some sounds if we no longer perceive them to be a threat. Women do seem more susceptible than men.

In January a team from McGill University in Montreal reporting in the Journal of Sleep Research found that while mothers of multiple children reported more fragmented sleep than those with a single child, the number of children in a family didn’t seem to affect the father’s sleep.

As far as health risks are concerned, Stanley says it would be “inappropriate to extrapolate from the latest study that fitful sleep increases the risk of death from heart disease as from more than 8000 people studied, the numbers affected were small”.

However, previous findings have found that broken sleep is linked to hardened arteries and “there is a strong association between sleep apnoea and heart disease so you should seek advice from your GP if your breathing stops and starts at night”, Stanley says.

Fragmented sleep does put you at risk of anxiety, stress and depression. In January a study in Frontiers in Neuroscience suggested that interrupted sleep could be used as a predictor for future stress and, in a paper in the journal Sleep, Patrick Finan, a professor of psychiatry at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, reported that several nights of interrupted sleep may be tougher to deal with than getting fewer hours of sleep, with those who experienced it having low levels of positive emotions and high levels of negative mood in the morning. Yoga or six to eight sessions of cognitive behaviour therapy can help overcome anxiety associated with fitful sleep.

You go to bed feeling tired, but lie awake worrying

If you ruminate as soon as your head hits the pillow, you are not alone. Researchers from Baylor University in Texas found that as many as 40 per cent of people report difficulty falling asleep at least once a month.

“Anxiety is often the underlying cause,” Stanley says. “But the harder you try to fall asleep, the less likely you are to do so, leaving you more anxious.”

Start by reducing the information load we experience before bed — not just from the usual electronic devices, but also stimulating books or magazine articles that can affect some people’s ability to switch off and unwind. The Baylor study found that writing a detailed to-do list can help.

Of 57 healthy young adults asked to write either about tasks that they needed to remember to complete in the next few days (to-do list) or about tasks they had completed the previous few days (completed list), it was the to-do listers who fell asleep significantly faster.

“Rather than journal about the day’s completed tasks or process tomorrow’s to-do list in one’s mind, our study suggests that individuals spend five minutes near bedtime thoroughly writing a to-do list,” the researchers said.

Why you don’t need less sleep as you age

Our requirement for sleep does not diminish as we get older and is more or less fixed for life from early adulthood, even though our sleep patterns are prone to change.

“Essentially, you need the same sleep at 85 as you did at 25,” Stanley says. “What changes is your ability to achieve it.”

Some researchers have suggested that the ageing process disrupts our internal body clocks so that people go to sleep later and wake earlier than they did in their twenties and thirties.

This is partly down to a deterioration in function of the suprachiasmatic nucleus, the master clock that governs our circadian rhythms. Even when over-60s do drop off, the quality of sleep is not as good as when they were younger.

“With age our sleep does become more fragile,” Stanley says. “We start to lose some of the deep, restorative slow-wave sleep that is so important for leaving us feeling refreshed the next day.”

Make sure you get outside every day, preferably in the morning when light is at its brightest and for at least two hours a day. Daylight is one of the most powerful cues for maintaining the SCN and a lack of exposure to daylight has been associated with sleep problems in the elderly.

If you get less sleep, it doesn’t mean you’ll get dementia

In the new research published in Nature Communications it was found that older people who consistently reported sleeping six hours or less on an average week night from their fifties and sixties onwards were about 30 per cent more likely to develop dementia three decades later than people who regularly got seven hours’ sleep.

A previous study involving 2610 participants, published in February, found dementia was double among those who reported getting less than five hours’ sleep compared with those who got a regular seven to eight hours a night. These researchers from Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts, also suggested that, among participants with an average age of 76 years, routinely taking 30 minutes or longer to fall asleep was associated with a 45 per cent greater risk of dementia. There is, undoubtedly, a link between sleep and brain health.

“Alzheimer’s disease is characterised by clumps of the proteins amyloid beta and tau in the brain and deep sleep helps to wash these nasties away,” Stanley says. “If you are getting less sleep as you age, there’s a chance that you are not getting rid of them in the same way.”

Yet the links between dementia and sleep — or lack of it — are not clear cut. Sabia says “we cannot confirm that not sleeping enough actually increases the risk of dementia” and Stanley says it’s a “chicken and egg situation in which poor sleep patterns might be an early sign of Alzheimer’s, but not the cause”.

You are going through the menopause and not sleeping — what should you do?

Hormones often get blamed for sleep disruption among menopausal and postmenopausal women and a study published in the Journal of Menopausal Medicine reported the common complaints to be trouble falling asleep, frequent awakening and waking up too early.

“Usually, the actual cause of disturbed sleep during the menopause is not hormones directly, but temperature fluctuations which can be hormonally influenced but exacerbated by other factors,” Stanley says. At night our bodies want and need to lose heat to sleep and our body temperature drops by about 1C as we drop off.

“Anything that further increases your body temperature is not at all helpful,” he says. “Don’t eat a big meal or drink alcohol too close to bedtime, don’t exercise too hard late at night, which raises your body temperature, and do open windows and install a fan in your bedroom to keep things cooler.”

Hormone replacement therapy, if considered appropriate by your GP, can help to relieve severe hot flushes, Stanley says.

You wake up far too early and feel tired as a result

Our tendency to prefer mornings to evenings or vice versa — to be a lark or an owl — is mostly genetically determined.

“Approximately one quarter of the population are strongly morning people, one quarter are strongly evening and the rest are somewhere in between,” Stanley says. “You can’t train yourself to become one or the other and owls who have to wake up earlier for work than they would prefer can experience the grogginess of sleep inertia that lasts for 15 minutes to a couple of hours.”

For larks and owls, however, consistently waking up way too early is associated with depression.

“Approximately 90 minutes before we wake up our bodies produce cortisol, the stress hormone, in preparation,” Stanley says. “And it does seem that this occurs earlier in people with depression, causing them to wake before they feel ready.”

If early waking persists for more than four weeks and is affecting your wellbeing, it is time to see your GP to treat the underlying cause.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout