The BMI doesn’t lie … or does it? How fat are you really?

Amid backlash over the Body Mass Index, run the tape over the different ways to find out if you’re overweight.

Summoning up the courage to measure how out of shape you may have become during the pandemic is hard enough, but calculating whether you’re still within healthy parameters is further complicated because the experts disagree on how to do it.

This month came the latest call for the UK government to scrap the body mass index as the definition of a healthy weight. Around the world the BMI is a constant source of debate.

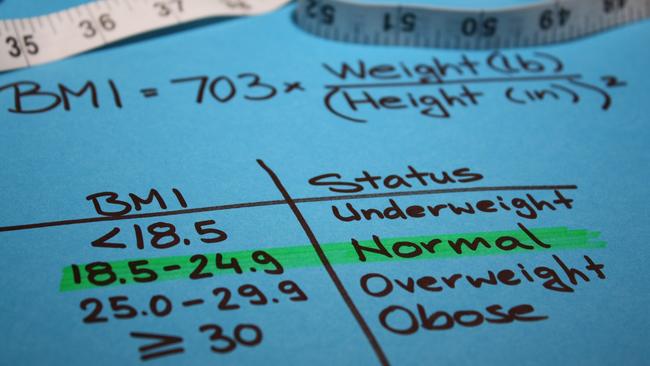

The BMI is a ratio of weight in kilograms to the square of someone’s height in metres — if your BMI is 25-29.9 you are classified as overweight. Levels of 30 and above and it is classed as obese. It is a quick and simple but rudimentary calculation that can produce a huge variety of misleading results.

Dr Margaret Ashwell, an honorary fellow of Britain’s Nutrition Society, says the BMI is too often used out of context and “was never really intended to be used as an individual measure”, as it is now by so many people. A central criticism is that, as a mathematic formula, BMI does not take into account muscle mass, bone density, racial and gender differences or overall body composition, meaning that a muscular athlete can be classified as overweight or obese despite having less than 10 per cent body fat.

“Of greater concern is that BMI does not distinguish people with excess central obesity, and we know it is central obesity that is the harmful fat not only for non-communicable diseases such as diabetes and heart disease but also for the severity of communicable diseases such as COVID-19,” Ashwell says. “We also know that some people within the normal BMI range of 18.5 to 24.9 can have risky central obesity and that this early warning sign is overlooked if BMI alone is used.”

Still, its popularity persists because it serves a purpose. “It can produce extreme results among the superfit, but for most people it will work as a rough guide,” says Susan Jebb, a professor of diet and population health at the University of Oxford. “It tells you where you lie on a continuum of risk.” Researchers value its simplicity.

“I have used BMI in my own research as an approach to define obesity and recognise that sometimes it is the best we have,” says Dr Sarah Sauchelli Toran, a senior research associate in nutrition at the University of Bristol. “Better tools that can break down body composition are expensive, even for clinics and labs.”

And Jebb says that, while it’s by no means a perfect predictor, its use is “borne out of millions of measurements in studies looking at health” and “every single time a high BMI is associated with problems ranging from cardiovascular disease to knee problems going up”.

For the rest of us there are other options for tracking our relative fatness and we should not restrict ourselves to using BMI as the only measurement. “People who use BMI to see where they stand should be aware of its many weaknesses,” Toran says. “Do not reach conclusions about your individual health risk based solely on your BMI.”

The more approaches the better. Any form of self-monitoring, even if it is just checking yourself in the mirror or pinching an inch to see if your waistband is tighter than it was, is helpful for most people in the long term — the exception being those predisposed to disordered eating, for whom it can cause anxiety. “The best thing you can do is just keep tabs on your own weight and health over time,” Jebb says. Here’s how:

Tape measure test

How it works: Wrap a tape measure around your waist at a midpoint between the bottom of your ribs and top of your hips.

What it tells you: How much weight you have around your belly. Carrying too much there is a risk factor for heart disease, strokes, cancer and type 2 diabetes.

Pros: “It provides a better estimate of abdominal fat than simply getting on a set of scales,” Toran says. When done properly it is said to be accurate within 5 per cent of scientific measures such as underwater weighing when it comes to assessing body fat value.

Cons: Toran says it is not “without its limitations” and is not recommended for people with a BMI of 35 or higher, for whom these readings can be unreliable. Plus we tend not to be very good at it. “There’s a big margin for error,” she says. “If you are using a tape measure at home you need to make sure that you measure in the same place every time so that readings are consistent.” Ashwell says that, compared with the waist-to-height ratio (below), it’s not as reliable at predicting serious obesity-related health problems.

String challenge

How it works: You’ll need a piece of string. “Use it to measure your height, then cut or fold it in half to see if it fits around your waist,” Ashwell says. “If the half length of string doesn’t reach around your waist, it is a sign you are carrying too much fat around your middle.”

What it tells you: The waist-to-height ratio provides another measure of belly fat. “A ratio of 0.5 has been shown in many populations to be the point at which health risks start to increase for men and women,” Ashwell says.

Pros: “It’s based on a remarkably simple public health message to keep your waist to less than half your height,” Ashwell says. “There is now plenty of evidence from all around the world to show that waist-to-height ratio is a better predictor of morbidity and mortality than BMI.”

Cons: Cheating is an issue, Jebb says. “It’s easy to breathe in or out, affecting the result,” she says. Ashwell says it’s best to perform the test no more than once weekly. “And you need to be consistent in where you measure your waist circumference every time you do it.”

Basic bathroom scales

How they work: Step on, step off.

What they tell you: Your total body mass – bones, organs, fat, the lot.

Pros: A cheap set of scales can be more accurate than you might think. In tests conducted at Rutgers University, while a set of old-fashioned dial scales were significantly less precise than digital scales, they were not considered so way out as to skew BMI scores. False readings were more likely the result of people using scales on wonky floors or in steamy bathrooms that affected the mechanics of the device.

Regular, even daily, weighing can be a big motivation for some people to stay in shape. In a study in which Jebb was involved, people who weighed themselves daily and recorded their thoughts and concerns as they stepped on to their bathroom scales were more likely to lose weight than those who didn’t weigh themselves.

Cons: Regular weighing is not recommended for everyone. “For people predisposed to disordered eating, self-weighing can cause a lot of anxiety,” says Karen Coulman, a clinical lecturer at the University of Bristol’s medical school.

Daily variations in results also need to be taken with a pinch of salt. Toran says: “Our weight changes quite a lot on a day-to-day and even weekly basis due to many factors including water in our body, and what and how much we have eaten recently.” Don’t stress about the decimal points. “You shouldn’t worry if you weigh 0.8kg more on one day compared to the day before,” Toran says.

Pinch test

How it works: An upgrade of the “pinch an inch” test using skin fold callipers to measure skin fold thickness at three locations — usually the chest, abs and thigh. Personal trainers still love this one and it’s a mainstay at many gym inductions. Results are processed using a standard test (or an online tool) to provide a body fat percentage.

What it tells you: A measure of your subcutaneous fat – the blobby stuff stored between our skin and muscles. A high body fat percentage is considered a risk factor for heart disease, raised cholesterol and blood pressure. As a rough guide, a body fat percentage of 25 or higher for men and 32 or higher for women is considered too high, with some studies suggesting healthy percentages for women aged 20 to 39 are between 21 and 32 per cent (8 to 19 per cent for men of the same age), rising to 23 to 33 per cent (11 to 21 per cent for men) at 40 to 59 years, and 24 to 35 per cent at 60 to 79 years (13 to 24 per cent for men).

Pros: The most accurate way to measure body fat is with techniques such as underwater weighing, air displacement BodPods or DEXA (dual energy x-ray absorptiometry) scans, which are mostly found in labs and carry a hefty price tag. So the draw here is that it is cheap. “It’s a better indicator of body fat than a set of scales,” Toran says.

Cons: It’s not a gauge of health unless combined with other measurements such as the waist-to-height ratio. “There are no standardised tables that take into account age and ethnicity and it won’t tell you if fat is lying in risk areas of the body,” Toran says. “In that respect it is similar to BMI measurements when used in isolation.” It’s also easy to get wrong – ideally you need the same person to test at precisely the same points each time.

Smart scales

How they work: Most use bioelectrical impedance, which measures how quickly electrical currents pass through the body (they will flow more easily through water in blood and muscle than they do through bone and fat) to measure body fat.

What they tell you: Body composition statistics, including body fat.

Pros: It is quick and easy, and can provide a rough guide of your fat-to-muscle ratio.

Cons: They are expensive and not hugely reliable. “Even the high-end brands use measures based on mathematical algorithms that are prone to misleading results,” Toran says. “And they don’t take into account where the more risky body fat lies on your body.”

Dehydration can affect results, over-estimating the percentage of fat. Studies have shown smart scales to produce widely different readings, over-estimating body fat in lean people and underestimating it in the overweight. One review by Consumer Reports in the US found that the most accurate smart scales were still 21 per cent off lab-based readings and the worst offenders were off by 34 per cent. Not suitable for people with pacemakers.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout