What happened in Syria? How rebels overthrew Assad in 24 hours

In the end there was no final stand or fearsome battle to salvage the regime - instead, the dictator’s soldiers left their weapons and fled.

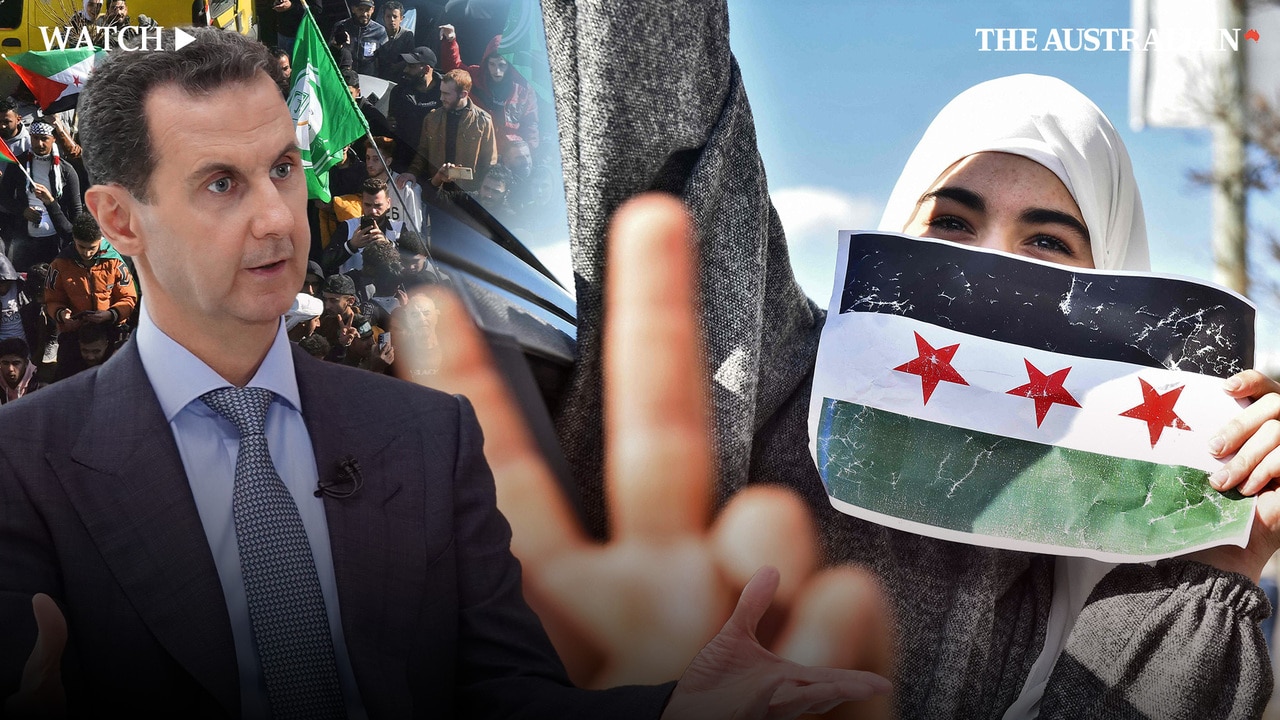

Just about the time Bashar al-Assad was packing his bags and preparing to flee Damascus, Syrian state television was playing Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake on loop. The president, said his office, was busy with “constitutional tasks”.

There seemed little to worry about for a man who has made a brutal habit of survival. His military had pledged it would defend the capital with a “ring of steel” while Assad’s backers in the Kremlin and Tehran vowed not abandon an ally who, for all intents and purposes, appeared ready to go down fighting.

By dawn on Sunday, however, the dictator, his British wife, Asma, and their children had disappeared. Damascus had fallen and, after ruling Syria for 24 years, Assad had been removed in just 24 hours.

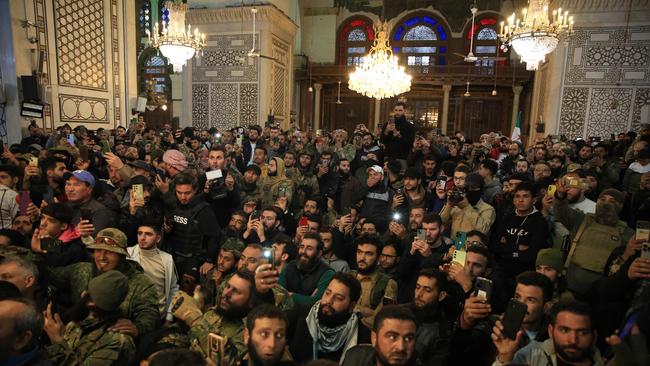

In his absence, thousands of residents of Damascus poured into the streets. In scenes reminiscent of the fall of Colonel Muammar Gaddafi in Libya in 2011, they stormed his palace, walking out with trophies ranging from crockery to the Assads’ photograph albums. They held up to video cameras prosaic snaps of family trips to the beach, one with Assad in swimming trunks, or of Asma holding their new-born children.

Video footage showed crowds in al-Rawda presidential palace, as children ran through the grand rooms and men slid a large trunk across the ornate floor. Several men grabbed gilt chairs to take home as souvenirs. At the Muhajreen palace, meanwhile, others gawped and the sheer gaudiness of decoration.

“My feelings are indescribable,” Omar Daher, 29, a lawyer in Damascus said. “After the fear that he [Assad] and his father made us live in for many years, and the panic and state of terror that I was living in, I can’t believe it.”

“Damn his soul and the soul of the entire Assad family,” another reveller in the city said. “It is the prayer of every oppressed person and God answered it today. We thought we would never see it, but thank God, we saw it.”

There even appeared to be the first stirrings of a long-cowed free press. Syria’s al-Watan newspaper, which was historically pro-government, wrote: “We are facing a new page for Syria. We thank God for not shedding more blood. We believe and trust that Syria will be for all Syrians.”

The newspaper added that reporters should not be blamed for the news of the past decade. “We only carried out the instructions and published the news they sent us.”

Such scenes were still unthinkable, even when the rebels first swept into Aleppo from their stronghold of Idlib last week. The ease with which they captured Syria’s second largest city was shocking.

Within days, Hama, too had fallen. Even at the height of Syria’s civil war, rebels had been unable to capture this city. Yet what was to come was unthinkable.

The rebels, under the command of Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, a former al-Qaeda commander, swept through Damascus, liberating thousands of prisoners held for years in Assad’s dungeons, as crowds turned out to celebrate.

The Syrian army’s underpaid soldiers put up little resistance and its self-enriching officer corps swapped their uniforms for jeans as news spread of the rebel approach.

There were no Russian air strikes to strengthen their morale, no Russian muscle, no Russian intelligence operation. Nor did Hezbollah units spring to Assad’s defence as Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) and affiliated opposition groupings swooped from the north.

Russia and Iran had promised to send their support to Assad but by then it was too late. There was no great battle for Damascus, no final stand by Assad as the political dynasty that ruled Syria for more than 50 years unravelled in a night.

“There was no real fighting involved,” Danny Mekki, a Syrian journalist and analyst who witnessed the regime’s final hours in the capital, said. “I spoke to people there and they said the regime was just running away. There were videos of soldiers just running away and leaving their weapons.”

No one had expected Assad to go down without so much as a whimper. “No one envisaged this, not even the Syrian opposition envisaged this,” Mekki said. “They were winging it.”

But the forces that came together to bring down Assad, just as it appeared that he was more in control of the country than at any point since 2011, had been bubbling away for years.

The front lines had been frozen since 2020, with Assad in control of the bulk of the country while the rebels and the opposition were confined to the northwestern province of Idlib and the east.

Assad, meanwhile, was busy rehabilitating himself internationally — Arab governments that had expelled him from the Arab League re-embraced him, arguing that he was an evil they had to live with.

The United States and Europe were contemplating lifting their sanctions on his government, in part to encourage him to sever his ties with the Iranians, who along with Russia had propped up his regime during the civil war.

Yet all the signs were there, a senior Arab diplomat said. “He who could read, should have read it long ago,” he said.

Egypt, other Arab countries and Turkey urged him to start reforms and reconcile with opposition groups but he rebuffed them. They also urged him to crack down on the production of narcotics that were flooding their countries, and he ignored them as the drug revenue brought billions to his coffers.

In the meantime, he hollowed out his army as the western sanctions took their toll, although he still managed to enrich himself.

“That son of a whore has billions of dollars but he couldn’t spare a few million for fuel for his tanks,” said another Arab diplomat who has worked on Syria.

In a surreal last-ditch effort to rally his troops, Assad ordered an increase this week in officers’ pay, from a measly $30 a month. It was too little, too late. Officers had taken to sending their soldiers home so they could collect their salaries, said Joshua Landis, who leads the Centre for Middle East Studies at the University of Oklahoma.

When the rebels advanced, they were met by undermanned and demoralised forces who fled and left behind their weapons and uniforms. Several thousands of them packed into trucks and fled to Iraq; others just went home.

The advance caught the Russians and Iranians by surprise. Russia had a handful of jets remaining in the country, having diverted its fire power to Ukraine.

Iran had been hammered in Syria by Israeli air strikes over the past year, and Hezbollah in Lebanon —the force that had early on helped Assad to retake Homs and other Syrian cities, was nursing its wounds from its devastating war with Israel that only ended this month.

Hezbollah hastily mustered hundreds of troops to Syria to fight alongside Assad’s forces but along with the Russians and Iranians realised that there was no army for them to fight alongside. In apparent retribution for its support of the regime, the Iranian embassy in Damascus was stormed by rebels on Sunday.

“Officers were getting paid $30 a month, and enlisted men were making $10 a month,” Landis said. “No one, of course, could feed their families on this paltry pay. Soldiers were taking money from merchants and others at checkpoints because Damascus wouldn’t feed them, and officers would send their men home so they could take the soldiers’ money.”

In some areas, such as Deraa outside Assad’s stronghold of Damascus and the coastal bastion of his Alawi minority, armed groups that had reconciled with his government held sway. They had been allowed to keep their light arms, and they remobilised as more territory fell to the rebels.

His elite Tiger Forces, a largely Alawi militia, had made a stand in Homs but they were more focused on protecting the Alawi heartland. Other minorities that had once supported Assad, such as the Shia Ismailis and the Druze, jumped ship, with the latter seizing the southern city of Suwaida at the weekend and declaring it free of the regime.

“He was an arrogant SOB,” Landis said. “He needed to compromise with the Kurds. The Kurds have America’s ear, he needed to get backers. He didn’t help the Druze — they’ve really abandoned the regime — and so have the Ismailis. Most importantly, he doesn’t speak to the Syrian people.”

By contrast, Assad’s main opponent, Jolani, had taken the opposite tack. Jolani returned to fight in Syria at the behest of Islamic State’s Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, before turning against him then severing his ties to the organisation.

His current group, HTS, is designated as a terrorist organisation by US, Britain and others, and he is now seeking to allay their fears, and those of the minorities, that he would impose a jihadist government. His efforts seem to have worked, at least toward his domestic audience.

“Jolani has made extraordinary adjustments, got rid of his jihadists and reassured the Christians. Assad has done none of that,” Landis said.

The make-up of the rebels — Islamists, American-backed Kurds, Turkish-backed militias — may sound like a recipe for further internal conflict but many Syrians hope that they will work together on an interim government and then, elections.

Anas Salkhadi, a rebel commander who appeared on television, said: “Syria is for everyone, no exceptions. Syria is for Druze, Sunnis, Alawites and all sects. We will not deal with people the way the Assad family did.”

“I think the Syrians are really tired after 13 years,” Yasser Alhaji, who heads foreign affairs at the Syrian Interim Government, an opposition group, said. “Everyone will make concessions to make things work. We have no other choice.”

Syrian exiles around the world of all stripes, Sunni Muslim, Christian, Alawite and secular, rejoiced at the end of a dictatorship that had persecuted their families and driven them out with barrel bombs.

The road from Beirut to Damascus was filled with cheering refugees, saying that at last they could return home. “I’ve come here to celebrate,” said 19-year-old Mohammed Ahmed Khateeb, who had been born in Aleppo but lived most of his life in exile in Lebanon. “Thank God, he has delivered us from that dog Assad.” he said.

Another man, 40-year-old Mohamed Hassan, pulled up at the border in an open-topped lorry, saying he wanted to pick up anyone else who wanted to come with him. “We want to take everyone with us,” he said. “this is a great day and some people don’t have cars to return to their country. We want them all with us.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout