Bashar al-Assad, an ophthalmologist who became a dictator, is the last of a despotic dynasty

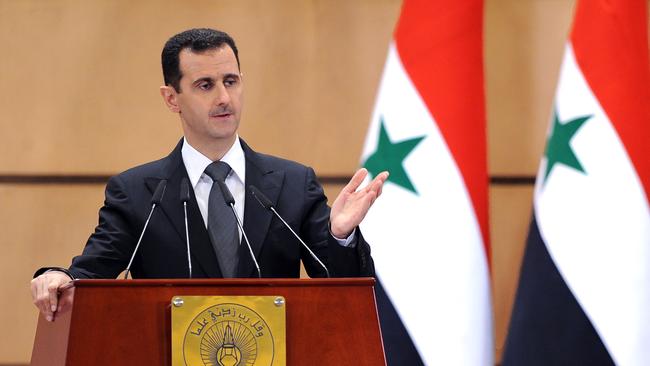

Once a self-styled moderniser, Syria’s president bought time with a harsh crackdown, but his government eventually succumbed to its many enemies.

Bashar al-Assad was never expected to rule Syria. That job was meant for his older brother, Basil, who trained as a military commander while Bashar studied to be an ophthalmologist.

He wasn’t expected to be the last of the line for his family’s despotic dynasty, either — at least, not this soon.

A lightning advance by Syrian rebel groups took just over a week to roll through the country’s major cities and into the capital Sunday, driving Assad to flee and bringing an end to a regime that had ruled for 54 years. Assad travelled to Russia, where Moscow granted him and his family political asylum, Russian state news agency TASS reported Sunday.

Russia and Iran, which had saved his government after a civil war erupted more than a decade ago, did little to help this time as his enemies closed in. Arab governments turned away his entreaties for support. In the end the army and security services that terrorised, tortured and used chemical weapons against Syrians just melted away, leaving Assad exposed and alone.

He fled the country as the rebels advanced, Syrian security officials said. His wife and children left for Russia in late November, while his brothers-in-law left for the United Arab Emirates, Syrian security officials and Arab officials said.

The Assads’ fall is in part due to the wars in Lebanon and Ukraine, which damaged Iran-backed Hezbollah and Russia, distracting them from the threat in Syria. But it is also due to years of economic mismanagement and brutality by Assad’s government.

After initially positioning himself as a moderniser of Syria’s economy, Assad launched a brutal crackdown once protesters took to the streets. The violence unleashed a civil war that destroyed entire cities, displaced more than half the population, redrew the balance of power in the region and unleashed waves of refugees whose arrival in Europe helped fuel anti-immigrant sentiment.

The crackdown delayed the end by more than a decade, but eventually the resulting anger and deprivation doomed his rule.

“If I were to describe him, I’d say he’s affable and unyielding,” said Robert Ford, former U.S. ambassador to Syria. “He will go down in history as a brutal dictator that thrust his country into a horribly destructive and bloody civil war. This will always be his legacy.”

Second son

Bashar al-Assad is the second son of Hafez al-Assad, a military officer who led a coup in 1970 and ruled Syria for nearly 30 years. Born in Damascus, the younger Assad was just 5 years old when his father took power. Sandwiched between more charismatic siblings who showed an early interest in the military and politics, Assad was a meek child interested in science and medicine.

He was a teenager when his father quelled an uprising by the outlawed Muslim Brotherhood by razing the town of Hama and killing an estimated tens of thousands of people in army shelling. It was a chilling blueprint for how the Assad regime would deal with opposition.

A young man who often looked at the floor when greeting strangers, Assad attended the Lycée Francais in Damascus and studied medicine at Damascus University. He moved to London in the 1980s to become an ophthalmologist, inspired by the ability of science to give people sight. While studying medicine in the U.K., he met and married Asma Akhras, a London-born Syrian banker. Meanwhile, back in Syria, Basil drove sports cars and rose to the rank of colonel in an elite army unit.

When Basil was killed in a car crash in 1994, Bashar flew to Damascus, where at the age of 29 he was thrust into the role of unlikely heir. Speaking at Basil’s funeral, he stared down at a fistful of printed pages that flapped in the wind. “My beloved brother Basil, I cannot comprehend your death or find the words to describe it,” he said, as his father looked on.

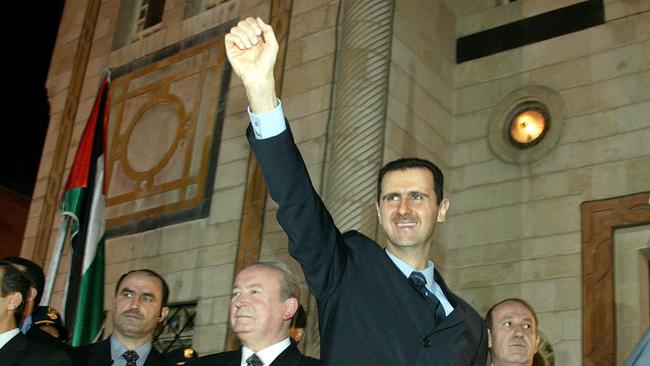

“I think he always saw himself as not measuring up in his father’s eyes, ” said Dennis Ross, a senior American diplomat in the Clinton, Bush and Obama administrations. “So some of that, no doubt, has contributed to his need to prove that he’s strong.” To prepare him to take power, Assad was fast-tracked through the military. After his father’s death in 2000, Syria’s rubberstamp parliament amended the constitution to allow someone younger than 40 to become president. Assad was 34 at the time. He assumed the presidency via an election in which his name was the only one on the ballot, receiving 99.74% of the vote.

He initially played the role of a modernising leader — the region’s youngest at the time. Computer-savvy, fit and fluent in English, he promised institutional accountability, changes to the socialist economy and political liberalisation. His first year in office became known as the Damascus Spring, as the government allowed a modicum of political expression and the stirrings of a civil society. Damascus opened its first stock exchange. Vogue magazine profiled his wife in 2011, portraying her as glamorous and chic, “a rose in the desert.” That same year, a revolt swept the Arab world. Tunisia’s leader fled the country. Egypt was gripped by a revolution that would eject President Hosni Mubarak from power. Assad, who had yet to face protests against him, received a new American ambassador in Damascus.

The ambassador, Ford, rode to the presidential palace in an armoured car. After presenting his credentials, he was ushered into a grand room with marble floors and was seated next to the president. Delicately raising the topic of the regional unrest, Ford said, “A hot wind is blowing from North Africa. Are you worried about it coming here?” Assad cast the comment aside. “My people love me,” he said, according to Ford. “We’re leading the resistance against Israel.”

Burn the country

In March 2011, protesters filled the streets of Damascus, Aleppo and other Syrian cities. Assad’s security forces opened fire on the crowds. As the protests grew into an armed insurrection, he upped the ante, turning to tactics that included chlorine and sarin gas attacks, abduction of opposition activists and the use of barrel bombs — makeshift explosives that regime soldiers dropped from planes and helicopters on rebel enclaves. Assad’s forces laid siege to rebel towns, forcing civilians to eat grass to survive, according to the World Food Program.

His supporters spray-painted a slogan on walls: “Assad, or we burn the country.” Assad is subject to an arrest warrant in France on war-crimes charges that he denies.

Within two years, armed opposition groups controlled a swath of northern Syria, the south near the border with Jordan and parts of the Damascus suburbs. Assad ceded control of Syria’s northeast to Kurdish militants, who would later ally with the U.S. in the fight against Islamic State extremists.

Assad clawed back some two-thirds of the country after a lethal military campaign backed by Russian air power and Iranian-allied militias such as Lebanon’s Hezbollah.

Many of the rebels were confined to a small enclave pinned against the Turkish border hosting 2 million displaced people, many of them in camps. The last major Russian and regime offensive ended in 2020. The years of fighting had killed hundreds of thousands of Syrians and uprooted some 12 million others from their homes.

The civil war continued, but the front-lines remained static. His country was shattered, but Assad had survived.

“If he could have sat with the people since day one and talked to them and gave them a bit of their rights and gave them a bread and electricity since that time, a lot of Syrians would have not been killed, ” said Majd al-Jadaan, the exiled sister in-law of Maher al-Assad, Assad’s younger brother and commander of the Syrian army’s elite 4th Armored Division.

With the conflict on a low simmer, some regional leaders began to reach out to Assad, ending years in which some Middle Eastern powers had shunned him over his crackdown on his people. Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed, the influential leader of the U.A.E., flew to Damascus in 2021 to open a new era of relations with the Syrian leader. Saudi Arabia rekindled relations. Jordan reopened its border and resumed flights to Damascus.

Assad appeared to have won. But the country was shattered, and the government hollowed out. When a rebel group that had been building up its capabilities in the northwest launched a lightning offensive, his rule quickly unravelled.

“The regime just broke,” said Aron Lund, a security analyst with the Swedish Defense Research Agency, a government think tank. “It’s not the size of the battering, it was the door that was the problem.”

The Wall Street Journal

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout