Syria’s rebels bring no guarantee of stability, freedom or prosperity

Even if its advance towards Damascus is successful, the coalition of forces led by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham might not bring the rewards that the war-ravaged nation craves

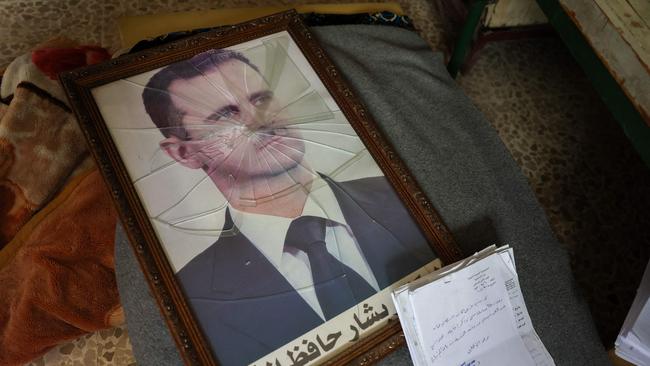

While Bashar al-Assad’s regime might be on its last legs, the Syrian people’s aspirations for freedom and prosperity are still a long way from being answered.

The rapidly developing events have shaken the region. Lebanon said it was closing all its land border crossings with Syria except for one that links Beirut with Damascus. Jordan closed a border crossing with Syria, too.

The rebels said early on Sunday that “the tyrant Bashar al-Assad has fled” and declared “the city of Damascus free”.

“After 50 years of oppression under Baath rule, and 13 years of crimes and tyranny and (forced) displacement ... we announce today the end of this dark period and the start of a new era for Syria,” the rebels said on Telegram.

In a speech broadcast on his Facebook account, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) leader Abu Mohammed al-Jolani said: “This country can be a normal country that builds good relations with its neighbours and the world.”

“But this issue is up to any leadership chosen by the Syrian people. We are ready to co-operate with it (that leadership) and offer all possible facilities,” he added.

“To all military forces in the city of Damascus, it is strictly forbidden to approach public institutions, which will remain under the supervision of the former prime minister until they are officially handed over.”

There is no guarantee of stability under those vying to replace him, including Jolani who has tried to distance himself from his movement’s al-Qa’ida past and emphasised his commitment to tolerance of minorities in Syria.

Jolani also declared that his anti-Westernism was in the past, despite his previous admiration for the 9/11 hijackers, and burnished his diplomatic credentials by urging Iraq not to allow Iran-aligned militias to enter Syria.

He is proving to be a smart and calculating politician. He may have sprung from the nest of the Islamic State in Iraq, where he went from Syria to fight almost two decades ago, but he realised a more moderate face was necessary if he was to avoid ISIS’s fate.

He took to wearing Western suits and trimmed his beard and hair. He worked with aid agencies to re-establish order and services in Idlib. He opened up to the Western media, largely ending the longstanding kidnap threat against them in Syria.

Jolani’s moderate pivot might be more effective in assuaging international audiences than in uniting Syrians around his rule. HTS is intensively clashing with Kurdish Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) rebels in Tel Rifaat to the north of Aleppo and any threat to Kurdish self-rule will brew further conflict.

HTS’s rule over Idlib has been marred by the devaluation of the Turkish lira, unrest against excessive taxation and kleptocracy, and the arbitrary detention of opponents for alleged collaboration with Russia and Hezbollah.

HTS rule is a possible mirror image of Assad’s regime. This means Syria’s future could be characterised by incessant conflict and economic deprivation.

The fall of the Syrian government began on November 27 when the rebel coalition led by HTS launched a rapid-fire offensive against Assad’s forces.

Barely a week later, Aleppo and Hama – Syria’s second and third largest cities respectively – had fallen under rebel control.

Emboldened by these successes, Syrian opposition forces then claimed the city of Homs and are now claiming to have freed the capital, Damascus.

Syria was divided into four – the regime in the major cities of Damascus, Aleppo, Homs, Hama and Deraa; the Turkish-backed rebels in the north; the jihadists of HTS, by now divorced from al-Qa’ida, in the northwest; and the SDF running the eastern cities of Raqqa, Qamishli and Hasakah.

Assad was facing a revolt on three fronts: HTS’s advance from the north; an uprising in the east, where an American-backed alliance led by Syrian Kurdish fighters had seized the city of Deir el-Zour; and in the south, where rebels said they had seized control of the city of Daraa.

The pace of HTS’s advance is exceeded only by its shock value.

After President Vladimir Putin of Russia and his Turkish counterpart, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, brokered the March 2020 Idlib ceasefire in Moscow, a mirage of authoritarian stability swept over Syria.

Facing no incipient rebel offensives, Assad won 95 per cent of the vote in the performative May 2021 Syrian presidential elections.

In May 2023, Saudi Arabia restored diplomatic relations with Syria and Assad triumphantly returned to the Arab League. The stench of war crimes floating around him was no longer accompanied by pariah status.

Although the Syrian civil war had seemingly transitioned into a frozen conflict and Assad appeared secure, there were cracks in the firmament.

The Syrian economy was in a state of full-blown crisis. During the second half of 2023, the Syrian pound’s value nosedived by more than 80 per cent to an all-time low of 15,500 Syrian pounds to the US dollar. The Syrian economy contracted by 5.5 per cent, inflation soared to 60 per cent.

Assad deflected blame from his own economic mismanagement to US-imposed sanctions that thwarted investment in Syria’s reconstruction. Nevertheless, the chasm between Assad’s $US2bn net worth and the hardship of ordinary Syrians was impossible to reconcile.

Despite cultivating an illusion of unbridled power, Assad was still at war with his own people. In his quest to vanquish the last vestige of opposition in Idlib in the northwest, Assad’s forces continued to bombard civilian areas with artillery attacks. The conversion of Sarmin, a small town near Idlib, into a zone of frontline combat exemplified this trend.

By October 2024, Assad’s forces were shelling Sarmin daily and three-quarters of its population was forced to flee to safer areas of northern Syria. These atrocities were largely ignored by the international community and the gradual reheating of Syria’s semi-frozen conflict went unnoticed.

Socio-economic desperation and enduring violence gave HTS fuel to sustain its resistance. HTS developed a domestic arms production industry and produced drones, mortar shells and guided missiles on a large scale. HTS showcased these capabilities when it killed more than 100 of Assad’s cadets at a military academy graduation ceremony in Homs in October 2023.

Nevertheless, Assad’s key ally, Russia, remained confident in the stability of his regime. Russia redirected Su-25 jets and S-300 air defence systems to the battlefields of Ukraine and did not completely replace the Wagner Group contingents in Syria that were expelled after Yevgeny Prigozhin’s June 2023 mutiny.

Assad’s future had hinged on the struggle for Homs. Now that it has fallen – the Syrian military appeared to collapse with stunning speed – Prime Minister Mohammad Ghazi al-Jalali said he was ready to take steps to hand over power to the transitional governing body, adding he was ready to co-operate with any leadership chosen by the people.

Erdogan fears the fresh upheaval in Syria will trigger a new refugee crisis.

Samuel Ramani teaches politics and international relations at the University of Oxford.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout