We have learnt the wrong lessons from 9/11

And here we are, with the 20th anniversary upon us, and the supposed lessons of what happened in the wake of the atrocities: the War on Terror and the attempts at “nation building” so apparently clear to everybody. But what I wonder is, 20 years from now, will the generation of 2041 think we took the right road in ditching the desire to intervene and help make life better for people in far-off countries? Personally, I doubt it.

In 1970 the American historian David Hackett Fischer wrote about what he called “the historians’ fallacy”. This consisted, partly, of “the tendency of historians, with their retrospective advantages, to forget that their subjects did not know what was coming next”.

It isn’t just historians who commit this sin. People who know the facts of what happened on that day and in the following years often underestimate what it felt like at the time and what it seemed to require of leaders. I wrote about it that day, and although I think I partly comprehended its significance, my concern was that the administration of George W Bush might in effect declare war in the Muslim world. He didn’t.

We overuse words like “trauma” these days to describe being very shocked, but 9/11 was genuinely traumatic. A year after the attack half of Americans, asked how their lives had been changed by the attacks, said they felt more afraid, more distrustful and more vulnerable.

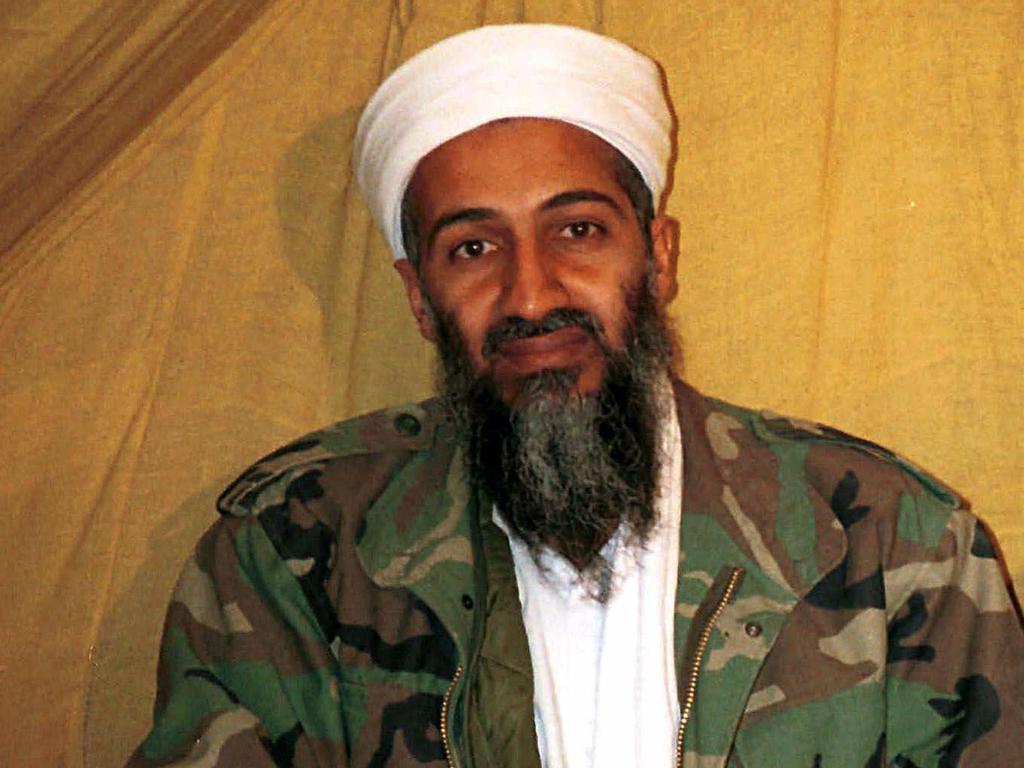

The form and scale of the atrocity was utterly unexpected. Anything was now thought possible. Who knew where these people might not strike next? From the very beginning the American public and their political representatives saw the attacks as an act of war, on the same level as Pearl Harbor. The invasion of Afghanistan and the removal of the Taliban government that had provided bases for the planning of the attack was the very least that an American president was going to do. But then came the longer-term questions. Bin Laden was on the run, but what further atrocities did this particular form of radical Islam promise, unless stopped?

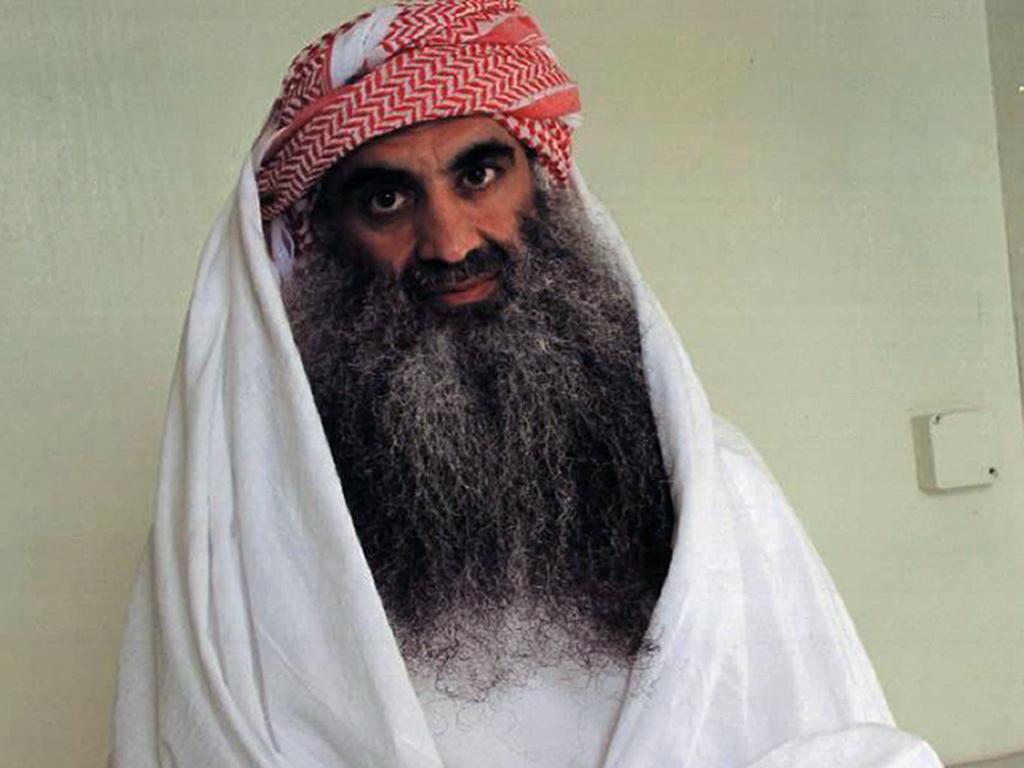

And it was particular. We’d had terrorism before. But the mass murder suicide terrorist was new. The 9/11 attackers wanted to die while killing as many people in America as possible and it didn’t matter much who those people were. It wasn’t stupid to ask what they would do if they got their hands on a “dirty bomb” or chemical or biological weapons. Imagine, for example, “Jihadi John” with access to novichok.

And this is where the new War on Terror coincided with another agenda, what has come to be called “liberal interventionism”. Growing from the horror of sitting by and observing the mid-90s genocides in Rwanda and in Bosnia, the Responsibility to Protect (R2P) movement took strength from successful interventions in Sierra Leone and Kosovo. Sometimes, it said, intervening militarily in the affairs of other states could be justified. And the kind of states – “failed states” and “rogue states” – most likely to harbour and even supply the new terrorism were sometimes the kind of states whose peoples had most suffered at their leaders’ hands: places like Libya and above all, Saddam’s Iraq.

This didn’t necessarily mean regime change by force, but as the foreign policy expert Sir Lawrence Freedman has characterised the logic: “There was little point in a half-hearted engagement for that could mean watching helplessly as witnesses to massacres, as with Srebrenica in the summer of 1995. UN resolutions, of which there were many on Bosnia, needed to be enforced, and while the introduction of airpower could make a difference, this also required what came to be described as ‘boots on the ground’.”

But these twin post-9/11 strategies have had very different outcomes. The War on Terror – much derided and blamed – has, I would argue, been a success. This may seem a strange thing to say in a week when the Manchester concert bombing inquiry is continuing and the Bataclan trial in Paris is opening. But the fact is that most terrorism in the last decade in the global north has been conducted by single attackers or small groups using the most basic of weapons. The knife and the lorry have become the tools of the bloody trade.

An attack on the scale of 9/11 has not been repeated. Enhanced intelligence, sometimes intrusive surveillance, high levels of security have diminished or interdicted attempts at mass terror. And even the worst governments are probably reluctant to arm or permit the export of mass-casualty terrorism for fear of reprisal. It seems unlikely the Taliban will visit terror on anyone other than their own unhappy compatriots.

The reverse is true when it comes to liberal interventionism. Since 2013 when Barack Obama’s red lines in Syria were crossed with impunity by President Assad ordering his forces to attack rebels with sarin gas, it’s generally and all too easily accepted that “exporting democracy”, or even humane government, has failed and is dead. The debacle in Iraq and in the last month the fall of Kabul are seen as a vindication of that analysis. From now on intervention means lobbing an “over the horizon” munition at someone you hope is the enemy. Helping the people the munitions fly over (and occasionally hit) is a matter for aid agencies. My instinct is that were another Rwandan genocide to loom before us in the next period, made horribly and intimately apparent by the magic of social media, we would do as little as we did in the 1990s.

But this time, as in Syria in 2015, the supposedly captive populace of a failing or fascist state won’t stay around to be slaughtered or starved. Because the inescapable truth – evident every day this summer on the south coast – is that this is an even more interdependent world than it was 20 years ago. Just as we can see the images of mayhem in their countries on our phones, they can see images of our towns and cities on theirs. Those whose nations aren’t being built – the unprotected millions – no longer feel so constrained to stay where they are and suffer the consequences.

And that was always the one enduring lesson of 9/11. In your town or country the war may be “over”, the sun shining on a cloudless day. You may feel very distant from the troubles of others. And then the world comes to you.

The Times

I heard it first on the two o’clock radio news. An aeroplane has flown into one of the twin towers of New York’s World Trade Center. It was thought to be a light aircraft. I turned on the TV and a few minutes later saw the second aircraft glide into the second tower, removing any doubt I had about the nature of what I was seeing.