September 11 attacks: The day that changed the US and our world

The aftermath of 9/11 still reverberates across the globe two decades later. The chaotic, bloodstained departure of US forces from Afghanistan this week can be traced directly back to 8.45am on September 11, 2001

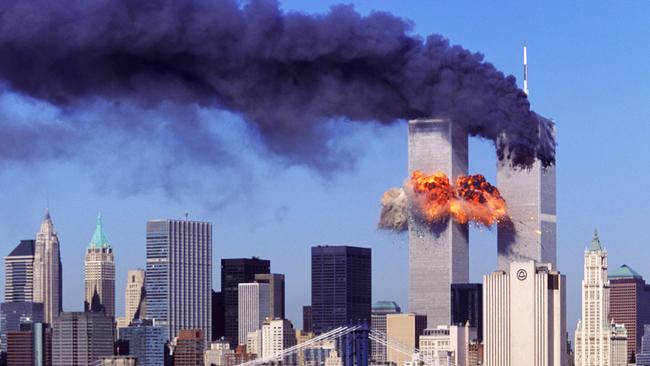

Two decades later, the aftermath of that day still reverberates across the globe. The chaotic, bloodstained departure of US forces from Afghanistan this week can be traced directly back to 8.45am on September 11, 2001, when terrorist Mohamed Atta flew American Airlines Flight 11 into the north tower of New York’s World Trade Centre.

By the end of that day, with smoke still billowing from the collapsed twin towers at Manhattan’s ground zero and from the Pentagon in Washington, the mindset of Americans was fundamentally altered. A fervent desire to prevent another terrorist attack on US soil led America into a 20-year war in Afghanistan, a decade-long conflict in Iraq and the targeted assassination of terrorists across the globe. US foreign and defence policy became just as focused on Islamic extremism as it was on fighting large global wars.

The Middle East was convulsed by change and tragedy, Syria imploded and Islamic State was born, only to rise and then fall. Australia, as a close US ally and a target for terrorists, moved in lock-step with America, joining US-led international military coalitions in Afghanistan and Iraq while rooting out terror on its doorstep in Bali and at home.

But while much of the focus of this 20th anniversary of 9/11 will be on the resulting “war on terror” in Afghanistan, Iraq and elsewhere, the attacks also transformed life in the US in lasting ways.

For any American under the age of about 23, which is more than 25 per cent of the population, 9/11 is history rather than a lived experience. In other words, almost every college kid across the US today has no memory of that day.

“A new generation of young people were not even born when 9/11 happened and they are now trying to figure out what it was all about,” former New York firefighter Joe Pfeifer told me when I interviewed him in Manhattan several years ago.

“They didn’t live through it, they only see it later on film. For them it is now a historical event.”

Yet living in the US, as I did in New York before 9/11 (1996-99) and then afterwards in Washington (2016-21), you can’t help but notice how much 9/11 has had a lasting impact on the American psyche and on how Americans live. Those who were not born at the time also live with the aftermath of those terrorist attacks, even if many do not realise it.

The shock, horror and profound sadness of that day continue to lurk beneath the surface of American life, even if it isn’t always obvious. It speaks volumes that 9/11 is just about the only major news event in the US that hasn’t become a plaything of Hollywood or popular culture. This is incredible given that two decades now have passed.

With the exception of a handful of films, such as Oliver Stone’s World Trade Centre and Flight 93, both made in 2006, Hollywood largely has kept away from the topic. Even those films were criticised for being too much, too early, by relatives of those who were lost. Compare that with the countless films made about US involvement in World War II and in Vietnam.

Pfeifer, a fire chief who almost died in the north tower on 9/11, says: “I have talked to film writers and producers right here in my office, but then the movie never gets made. I think 9/11 was too painful because people experienced it in real time. For big movie producers who want to make films, I think they feel it is too painful to see.”

Film and television producers struggle to deal with historical footage of the towers, uncertain whether they should keep them in or edit them out. Sex and the City, The Sopranos and The Late Show were among those programs to edit out shots of the World Trade Centre at the time, and even now it is a topic of debate for shows set in New York before 2001.

The ongoing psychological scars of 9/11 also can be seen in the delicate juggle that the 9/11 Memorial complex at ground zero must deal with as it seeks to remember the event without re-traumatising visitors. The brilliant 9/11 Memorial Museum at ground zero, which opened in 2014, tells the harrowing stories of each of the four planes in separate booths, allowing visitors to avoid any one of them easily if they wish.

The museum has included but carefully curated many of the final telephone calls people made from the towers before they died to ensure the most heartbreaking are not included. For example, they chose not to include the recording of a woman in the towers who knew she was going to die and who spent her final minutes praying with the 911 emergency operator.

Arguably the most confronting part of the exhibition, the pictures of the people who jumped to their deaths from the burning towers, including the famous “falling man” image, are tucked away in a side booth so people make their own judgment as to how much trauma they wish to see or relive.

Each year for the past 19 years, the anniversary of the attacks has been commemorated at ground zero in a similar way. During a 102-minute ceremony the names of the 2983 people who died are read out, with silence at the precise moments when the four planes crashed and the two towers fell.

Since the first anniversary in September 2002, when ground zero was just a gaping hole and the then New York mayor, Rudy Giuliani, began the reading of the names, the solemn annual tradition has continued.

Today, two giant reflecting pools sit where the north tower and the south tower once stood, with waterfalls rolling down their walls and the names of each victim engraved in bronze panels surrounding the pools. White roses are placed on the names of those who would have been celebrating their birthday. Looming large above the site is the new Freedom Tower, One World Trade Centre, the giant building that replaced the twin towers in 2014 and that was constructed to withstand a plane flying into it.

The ground zero memorial complex has become one of the most popular sights in the US, attracting more than seven million visitors each year. Similar memorials outside the Pentagon and in the Pennsylvania field where United Airlines Flight 93 crashed also are popular. These have morphed into something of a pilgrimage for many Americans.

When I visited the Flight 93 National Memorial in southern Pennsylvania in 2019, 18 years after the attacks, there was a crowd of people standing and staring in silence at the empty green field into which the plane hurtled after the brave passengers attacked the hijackers.

The ongoing legacy of 9/11 in the US can be seen most obviously in the way it has permanently tilted the balance between civil liberties and security across American society. Air travel was transformed overnight by the hijackings and has been tightened further since.

The Transportation Security Administration was authorised by congress two months after 9/11. Thanks to 9/11, going through airport security to catch a plane in the US today is a largely miserable experience, requiring passengers to remove their shoes and belts, take out computers and liquids from carry-on bags, and walk through full body scanners before boarding. Behind the scenes, bags are scanned and passenger lists are checked against FBI no-fly lists. Flying in the US will never be the same again.

The sweeping changes to domestic surveillance laws after 9/11 included the creation of the Patriot Act six weeks after the attacks, giving intelligence agencies vastly greater powers to detect terrorists.

Civil liberties groups have mounted a two-decade campaign to wind back what they consider overreach by authorities and an infringement of their freedoms, but the tougher laws remain in place. Despite some critics, the laws have served their purpose because there has never been a large terrorist attack on US soil since 9/11. This is a stunning and largely under-reported victory that seemed a pipe dream 20 years ago amid the smouldering ruins at ground zero.

The post 9/11 crackdown also changed the way US governments on both sides of politics viewed immigration. The sprawling Department of Homeland Security was created months after 9/11 to help prevent terrorist attacks and to oversee border security and immigration, including customs and border control. The department’s unspoken task was to ensure terrorist groups like the 9/11 hijackers could not enter the US undetected. The attacks drove the US to enforce tougher and more restrictive immigration policies that were pursued by the Bush, Obama and Trump administrations. Donald Trump’s attempt at implementing his so-called Muslim ban would not have won broad support from Republicans if it wasn’t for 9/11.

“Immigration (after 9/11) was no longer a question about migration or who we are as a country or about labour market competition. It was a security issue; we saw the ‘securitisation’ of immigration,” University of Virginia political professor David Leblang says. “That changed the nature of immigration enforcement quite dramatically.”

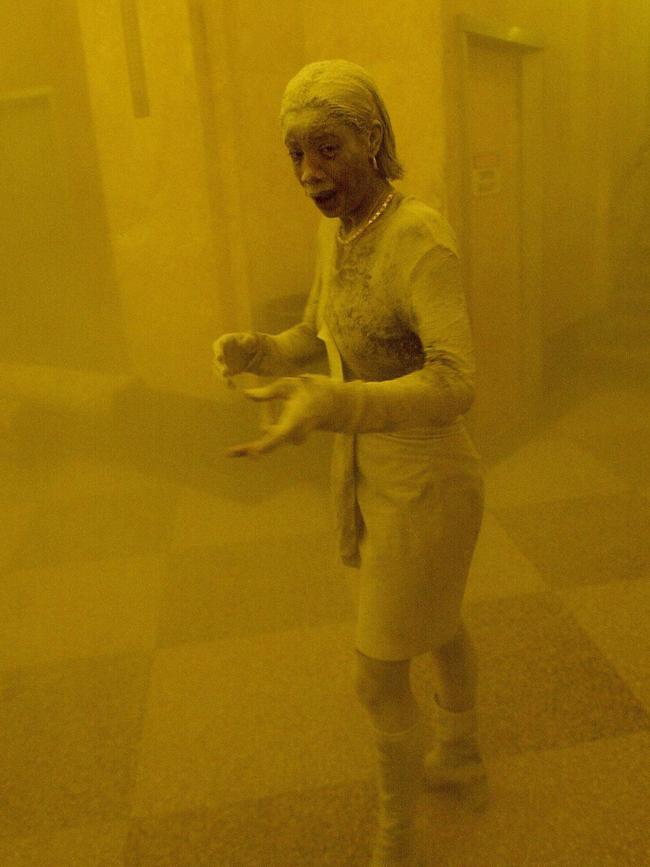

One of the saddest legacies of 9/11 is the growing number of people who have fallen ill and now are dying from exposure to the caustic dust and toxic pollutants at ground zero and surrounding parts of southern Manhattan in the weeks and months after the towers fell.

The piles of smoking debris from the towers were a toxic soup, spewing up deadly dust from crushed concrete and shattered glass, lead, mercury and asbestos.

At least 80,000 people at the ground zero site, and as many as 400,000 living, working and attending schools in southern Manhattan, breathed this toxic air, which the US Environmental Protection Agency had wrongly claimed was safe at the time.

“We knew people were getting sick even when we were working on the pile (at ground zero), everyone had a burning throat and runny nose,” John Feal, a construction worker who helped clean up ground zero told me as we walked through the memorial site in 2018.

Feal said he had attended more than 180 funerals since 9/11, a small segment of the more than 2000 people, and possibly as many as 5000 who have died of liver and colorectal cancers and other related ground zero illnesses.

One of the best known survivors of 9/11, Marcy Borders, known as “The Dust Lady” after a famous photo was taken of her covered in white dust after the towers fell, died in 2015 of stomach cancer that she blamed on the toxic dust.

The advocacy of Feal and others over this mounting human catastrophe culminated in congress in 2018 authorising an extra $US10.2bn in compensation funds to ensure every victim of 9/11-related disease and their families would be covered for the rest of their life.

“It’s going to get worse because we haven’t seen the next wave of cancer and that’s asbestos cancers because they take 20 to 25 years to manifest,” Feal says. “There are still lots of dark clouds coming.”

A Pew Research Centre survey found an astonishing 97 per cent of Americans who were old enough could remember where they were when the 9/11 attacks took place. This eclipsed even the 1963 assassination of president John F. Kennedy (95 per cent) followed by the 2011 killing of terrorist Osama bin Laden and 1969 moon landing.

One outcome of the 9/11 attacks that did not last was the sense of national unity it sparked. For a time in the months that followed it seemed as if America stood as one, united in anguish. Shops ran out of US flags, crowds cheered firefighters and police and special postage stamps were released declaring “United We Stand”. In the 20 years since, the US has slowly frayed into a more polarised society from race to wealth to politics to the city-rural divide. Nothing symbolised these divisions more than the January 6 storming of congress by Trump supporters. It was the same building that was a probable target of Flight 93 on September 11.

But the 20th anniversary of 9/11 this week will be a rare chance to remind Americans what binds them rather than divides them. The service remains one of the few solemn moments that unites the country completely. Why? Because even after 20 years, that dark day continues to eat away at America’s psyche. It still hurts. As ground zero worker Feal told me simply: “9/11 is never over.”

Twenty years on there is still no single day more seared into the memory of Americans and Australians than the terrorist attacks of 9/11 in New York and Washington. All of us who saw them can remember exactly where we were at that moment. All of us struggled to digest the magnitude of the unfolding horror as the twin towers crumbled on our screens in real time, swallowing almost 3000 lives in an instant and changing the world as we knew it.