We don’t mean trouble, say Israeli troops on border with Syria

Israel says its foray into the Golan Heights buffer zone will stop terrorist groups forming – but it’s also capitalising on its neighbour’s power vacuum.

Bashar al-Assad’s jet had barely left the runway when the Israeli tank commander and his battalion found themselves bouncing across the border into Syria.

They were totally unopposed – the Syrian units that had defended the ceasefire line for half a century had abandoned their posts.

The rebel militias that took their places had little resistance to offer when Israeli armoured units advanced across what was supposed to be a demilitarised buffer zone between the two old foes.

Israel has said that it is occupying the buffer zone as a precaution after Islamist rebels deposed the Assad regime, but it has been more opaque about its operations in Syrian territory.

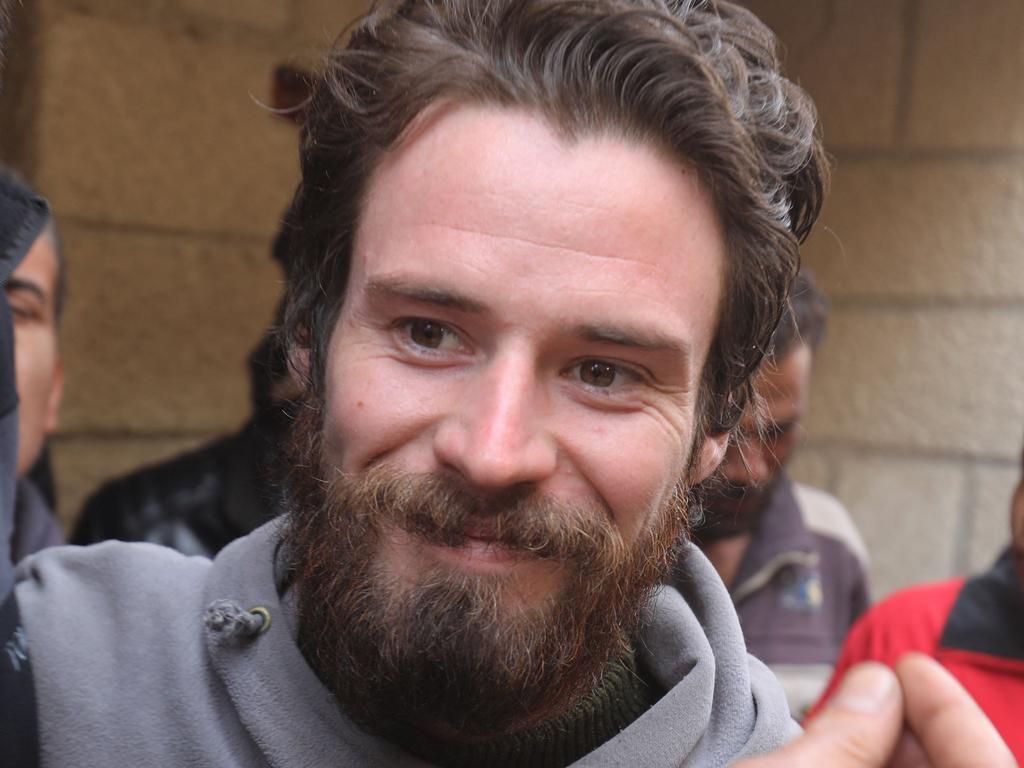

Tom, 21, a tank commander with the 188th Brigade, said his company had driven to a village roughly 5km inside the border, largely as an exercise in making their presence known.

The residents stayed indoors and out of their way. Those they did meet were neither friendly nor hostile.

“They probably don’t want us there, but what can they do? They know that fighting back would be useless,” said Tom, at a checkpoint along the border that he and his unit were manning.

Israel has justified its incursion as a preventive measure to head off the establishment of terrorist groups along its border, after 50 years of relative calm in the Golan Heights, whose western portion was captured by Israeli forces during the Six Day War of 1967.

In the face of growing international opprobrium, Benjamin Netanyahu, the Israeli prime minister, has doubled down. He told Jake Sullivan, the US national security adviser, that: “Israel will do whatever is necessary to protect its security from any threat.”

Assad was no friend of Israel and facilitated the supply of Iranian arms to Hezbollah through Syrian territory, but he was at least a man that the Israelis knew how to deal with. By contrast his successors, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), are an unknown quantity.

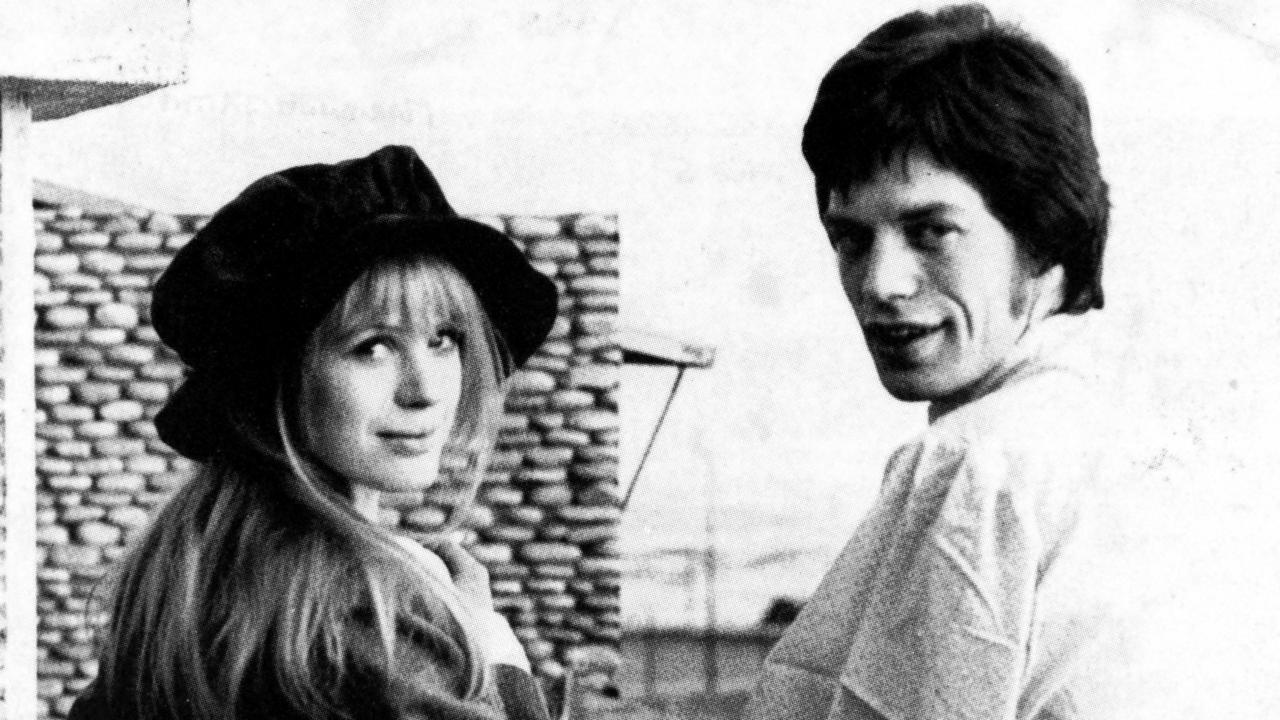

HTS’s leader, the jihadist known as Mohammed al-Jolani, who has now begun using his real name, Ahmed al-Shara, has made efforts to present himself as a force of equanimity. However, he is no Zionist. Hailing from the Golan Heights – his assumed name, Jolani, reflected that – he has said that his political awakening came at about the time of the Second Intifada, the uprising by Palestinians against Israel beginning in 2000, when he was 18.

“Who are these guys? That’s the million-dollar question,” said Captain Yinon Bitton, 42, who was leading his unit in target practice on a dormant volcano overlooking Syria. They too had crossed the border recently.

“We are simply telling the other side that we are here,” Bitton said of their border crossing. “We don’t mean any trouble, but we are here all the same.”

It is undeniable, however, that Israel is aiming to capitalise on its neighbour’s power vacuum. It launched 350 strikes on Syria’s military assets, destroying between 70 and 80 per cent of them, according to the IDF.

The Golan Heights plateau is also a considerable strategic asset because it overlooks four countries: Syria, Israel, Lebanon and Jordan.

On entering the buffer zone, Israeli soldiers occupied an abandoned Syrian outpost at the highest point of the Mount Hermon range, which looms above an Israeli base on a nearby peak.

At Majdal Shams, a town that sits on the border, Israeli tanks and D9s, military diggers used for building fortifications, were stationed alongside by the barbed fence.

Above them stood the town’s famous “shouting hill”, from where members of the Druze community – an ethno-religious minority who adhere to a Muslim offshoot faith – would shout to loved ones separated from them in 1967, in the days before mobile phones.

The Majdal Shams Druze were once renowned for their loyalty to Syria and staged regular protests against Israeli occupation.

Many older members of the community hung portraits of Assad and his father, Hafez, in their homes, either through genuine fidelity or fear that Syria might one day regain the town and come looking for collaborators.

That changed in the wake of Assad’s brutal crackdown on protests in 2011 and the civil war that followed. This week Druze took to the streets with Syrian flags to celebrate his downfall.

Iwan Abu Jabal, 20, is among a generation of Druze who carry Israeli passports, their forefathers having frequently rejected offers of citizenship.

He lives in one of the houses along the “shouting hill” and has a godmother in Syria who, in what is now a sentimental ritual, the family still commune with across the divide on special occasions.

“I’m happy that Assad is gone,” he said. “But that is Syria and this is Israel. We have our own lives to live here and they have their lives to live there.”

– Additional reporting by Michael Giladi

The Times