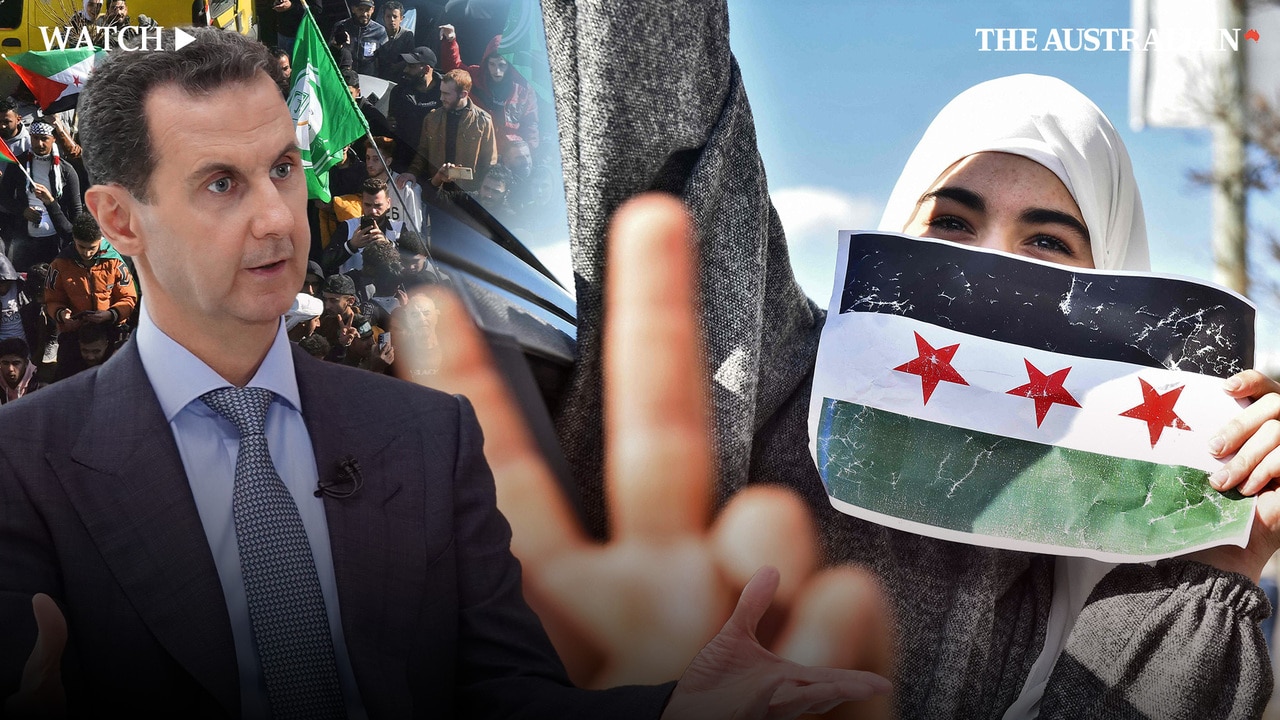

Who are the HTS rebels who captured Damascus and toppled Assad?

Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham launched a surprise offensive to seize Aleppo, Hama, Homs and Damascus in quick succession after years of Assad regime control | EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW

The fall of President Assad’s regime has been surprisingly swift, coming after many assumed the civil war in Syria ended five years ago — or even more.

However, rebels who were previously pushed back to a small pocket of resistance in northwest Syria, centred on the city of Idlib, have staged a stunning resurgence and taken the main cities of Aleppo, Hama, Homs and Damascus in quick succession.

The main rebel force is a jihadist group called Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, or HTS, who were formed from an affiliate of Al Qaeda. Now the world will be watching how they will establish their dominance in Syria, after Assad has fled.

Who are the HTS rebel group?

The name of HTS translates to “Organisation for the Liberation of the Levant” and it remains a sanctioned terrorist group in Britain, the United States and much of the outside world.

It was originally known as Jabhat al-Nusra, a Salafist Muslim jihadist group that emerged early in Syria’s civil war in 2012 and was confirmed as Al Qaeda’s affiliate in the conflict the following year, in opposition to Islamic State.

Led by Abu Mohammad al-Jolani, the so-called “Nusra front” was an aggressive Islamist force committed to replacing Assad’s regime with a Sharia-law-based government in the early years of the war.

However in 2016 he publicly split with Ayman al-Zawahiri, Al Qaeda’s leader, and rebranded the group, before merging with other rebel groups to form HTS the following year.

Who is their leader?

Jolani, 42, was born Ahmed Hussein al-Shara in Saudi Arabia, reportedly as the child of Syrian exiles. In the late 1980s, his family moved back to Syria, and in 2003, he travelled as a radicalised young man to join Al Qaeda in Iraq and fight the US occupation.

Like Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi, the founder of Isis, Jolani spent several years in an American prison in Iraq. At the beginning of the Syrian civil war he returned to fight there, founding Jabhat al-Nusra and taking on his nom de guerre.

How does HTS compare to other rebel forces – and has it lost its jihadist ideology?

Although for a time Isis became far more notorious and successful, HTS survived the fall of its rival’s so-called caliphate, and its independence proved an advantage on the battlefield in northwest Syria.

Unlike the Syrian Democratic Forces, which is constrained by its US backer; the regime, which was dependent on Russia and Iran; and the “mainstream” northern rebels which are tightly controlled by Turkey, HTS could act autonomously.

Jolani was also proving a smart and calculating politician. He may have sprung from the same nest as Baghdadi but he realised a more moderate face was necessary if he was to avoid Isis’s fate.

He took to wearing western suits and trimmed his beard and hair. He worked with aid agencies to re-establish order and services in Idlib. He opened up to western media, largely ending the longstanding kidnap threat against journalists in Syria.

Despite the acrimonious split with Al Qaeda, however, some analysts are not convinced that HTS has wholly renounced its jihadist roots. In Idlib, the group espoused a government guided by a conservative and at times hardline Sunni Islamist ideology.

Meanwhile, Jolani was also planning an attack, described initially as defensive, to deter airstrikes and other assaults on his positions by Assad regime troops. It was meticulously timed, with Russia and Hezbollah, the pillars of the regime’s defence, both weakened by their own wars, and the world focusing on Gaza and Lebanon.

What next for Syria after anti-Assad rebels seized Aleppo?

Nir Boms, a professor at the Dayan Center for Middle East studies, said: “Jolani needs to show a degree of pragmatism if he wants to succeed in bringing freedom to Syria. There are many patriotic Syrians who come from different sides — more Islamist, less Islamist, even Alawites — who would like to see their country back.”

Jolani has issued a number of statements vowing to unite Syria and, crucially, to protect minorities including Christians, Druze and Kurds. He has promised not to harm the Alawites, who backed Assad. But protests about HTS rule in Idlib, some of which have brought thousands onto the streets in opposition, suggest Jolani may struggle to bring unity.

“While he is somewhat open to the pragmatist view, he hasn’t shown us all his true colours yet,” said Boms.

What is the background to the offensive?

The Assad regime’s capture of Aleppo in 2016 had appeared to end the threat from the rebel forces — both pro-western and jihadist — which had risen against it in 2011 but were by then confined to the region of Idlib.

Front lines elsewhere stabilised in 2019 when the SDF, the western-backed Kurdish-led militia, overcame the last stand of Isis at Baghouz in Syria’s far east.

Syria was divided into four. The regime in the major cities of Damascus, Aleppo, Homs, Hama and Deraa; the Turkish-backed rebels in the north; the jihadists of HTS in the northwest; and the SDF running the eastern cities of Raqqa, Qamishli and Hasakah — the latter two with a Kurdish ethnic majority.

However, as Israelis and Palestinians have found, there is no such thing as a settled outcome in the modern Middle East. The regime and the jihadists continued to snipe at each other. Turkish forces staged attacks on the SDF because of the Kurdish elements’ close ties to the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), the guerrilla army that has fought Ankara for decades. Isis staged occasional minor comebacks.

Even in Deraa, on the Jordan border, where the war had been ended with a Russian-backed “reconciliation deal” rather than along a frozen front line, there were regular skirmishes.

What were the other factors involved?

These mini-battles were a reflection of the one fact that all sides — bitter local and global enemies — agreed: this outcome was not stable. Without territorial integrity, Syria could not hope to join the international order of nation states.

Assad still kept hundreds of thousands of opponents in prison, whose torture chambers continued to make him a pariah in the West. The regime may have won the war, for the most part, but it lost the peace as the economy crumbled under the weight of the regime’s corruption, western sanctions and the failure of Russia and Iran to support their ally except in military terms.

A final blow came with the collapse of the Lebanese banking system in 2020. It was where Syria’s elite class had kept their money for years, and it disappeared overnight.

Hezbollah, which had been Iran’s foot soldiers in Syria, helping to prop up the regime and ensure a flow of arms, were also crippled by Israel’s attacks and the war in Lebanon earlier this year.

Still, no one expected the rebel advances, except a few close observers of the strange political and ideological beast that HTS became after it divorced itself from al-Qaeda.

The Times