Vladimir Putin misjudges his greatest threat: the Russian people

Russia’s history is punctuated with revolutions rooted in mass protest and seldom have so many government opponents of disparate hues united against Putin.

Russia in the 1990s after the collapse of the Soviet Union was a wild and dangerous place. An alcoholic President Boris Yeltsin held court in the Kremlin. Mobsters were fighting it out on the streets. One day a rocket-propelled grenade fired from a busy road blasted through a wall in the American embassy, destroying a copying machine.

As the Sunday Times correspondent, I watched in fascination as the capital of a superpower slipped into anarchy and Yeltsin bombarded parliament in 1993 to dislodge rebels clamouring for the return of the Soviet Union. I will never forget the sight of documents fluttering down from the sky when a tank scored a direct hit on an office on the top floor.

Vladimir Putin, the sober, fiercely competent former KGB officer who succeeded Yeltsin at the end of the decade and steered his country back from co-operation with the West to confrontation, often evokes the “lost” 1990s as part of his survival strategy. The message is: without me, Russia will return to chaos.

Today, nevertheless, there could be real chaos: the arrest of the anti-corruption campaigner Alexei Navalny, after a botched attempt to assassinate him has unleashed the greatest wave of anger against Putin in his two decades in power.

Defying an intensifying crackdown on dissenters, thousands of people are expected to congregate outside the state security headquarters in central Moscow today demanding an end to Putin’s long reign and freedom for his fiercest critic.

This follows a giant explosion of anger against the regime last Saturday when tens of thousands of demonstrators braved threats of prosecution and subzero temperatures in more than 100 cities to call for Navalny’s release.

Now Putin faces a dilemma: should he risk turning Navalny into a martyr – or risk seeming weak in the eyes of his hawkish security forces by letting his biggest enemy go free. He appears to have opted for the former. But, perhaps to give the sinister proceedings an air of openness, Navalny has been allowed to go on denouncing Putin from prison.

“You won’t succeed in scaring tens of millions of people who have been robbed by government,” Navalny told a court on Thursday via a videolink. “Yes, you have the power now to put me in handcuffs, but it’s not going to last for ever.”

Navalny, 44, by training a lawyer, is famed for his video investigations into the luxury lifestyles of the elite.

The latest, about Putin’s £1bn ($1.8bn) pleasure palace on the Black Sea coast, has notched up more than 100 million views. It was released after Navalny was arrested and put in jail two weeks ago on charges of violating the terms of his probation. He has argued that he could not meet them because he was convalescing in a hospital in Berlin from an attempted assassination by poisoning that he has blamed on Russian security agents. He faces trial on Tuesday and possibly a long prison term.

Over the past few days, several of his allies, including Oleg, his brother, have been arrested. Anastasia Vasilyeva, a doctor, posted a video of herself playing Beethoven on her piano as police came to detain her. They were accused, bizarrely, of violating coronavirus restrictions by backing the protests last weekend.

The canny Putin has successfully navigated many an international crisis. Yet as he enters his third decade in power his mood seems to have changed.

“Putin is tired and bored,” said Mark Galeotti, honorary professor at King’s College London and author of A Short History of Russia. “He would like to step down if he could.” He has been observed glancing at his watch during meetings. But there is no succession device – and so he is trapped in power by public fear of the chaos that would ensue if he went.

For Tatiana Stanovaya, a political analyst with the Carnegie Moscow Centre, this is, in a sense, the secret of his survival. “The reasons for supporting Putin have changed,” she said. “Before it was for positive reasons, people felt proud about Russia. Now they vote for him out of fear that the situation could get a lot worse under someone else. They are afraid of a return to the Yeltsin era.”

Now, though, the Kremlin has cause for serious concern. Seldom have so many government opponents of disparate hues, right and left, young and old, united as they have in the past week around Navalny and against passive acceptance of Putin. Protest has always prompted alarm behind the Kremlin’s high, red walls, which are haunted by histories of revolutions rooted in mass protest, from the Bolshevik takeover to the death throes of communism.

“On both occasions, people overwhelmed the state, and this is Putin’s biggest fear,” said Sir John Sawers, head of MI6 from 2009 to 2014. “He’s not afraid of the West. His fear is his own people.”

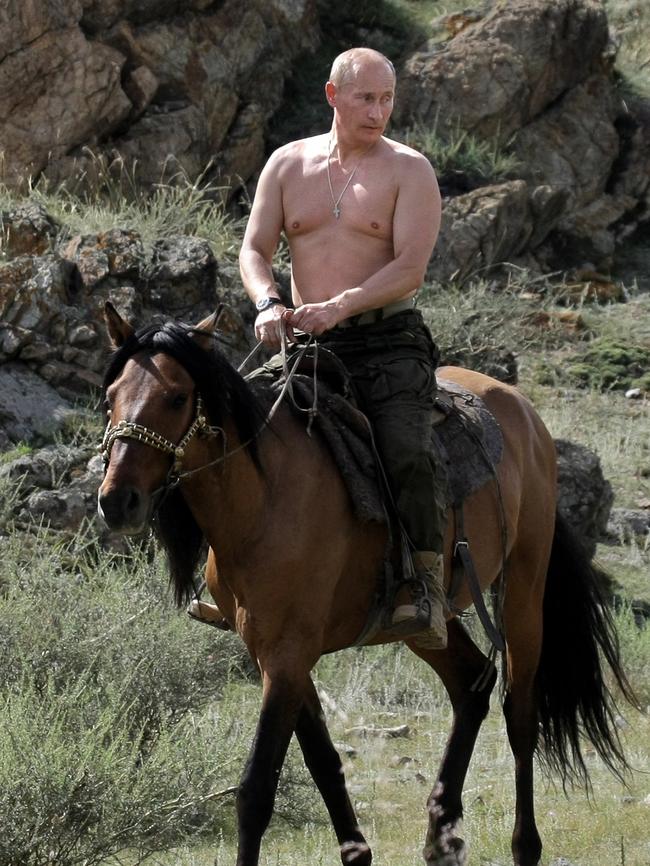

When Putin succeeded Yeltsin, nobody could have imagined that the bland and diminutive bureaucrat would become the longest-serving leader Russians have known since Joseph Stalin ruled over the Soviet Union. Helped by an economic boom in the 2000s, the younger Putin cleverly used bare-chested fishing expeditions in Siberia and other virile antics to craft an image of the president as a man of action: he could not only pilot a fighter jet or tag a wild tiger but would also restore national pride and Russia’s place in the world after the humiliation of the Soviet collapse.

At the same time, he and his cronies – many of them boyhood friends from St Petersburg – were alleged to be amassing vast riches. “The early Putin was pragmatic, the idea was to allow everyone to steal at home and bank abroad,” Galeotti said. “Nobody had signed up for some grand crusade against the West.”

A former communist zealot, Putin has attempted to clothe his regime in ideology, adopting an obscure nationalist thinker, Ivan Ilyin, as a guiding light of his regime. Another part of his ideological scaffolding is the Orthodox church. He has a personal confessor and engages in atavistic symbolism for the cameras – publicly immersing himself in icy water on the feast of the Epiphany this month.

For some observers, this is just window-dressing for a tenacious kleptocracy whose tentacles stretch all over the country and sustain the president. “There is a broad coalition of powerful Russians who benefit from the status quo, not just the richest oligarchs,” said Galeotti. “You can be a ‘minigarch’ too and benefit – it’s a generous, broad-based kleptocracy in which you have a lot of people who want to keep the system going.”

Conflict has nevertheless proved Putin’s strongest suit. A master of high-stakes diplomacy, he loves strutting the world stage and has given Russia a malevolent influence that matches its vast geography – it spans 11 times zones – but is out of all proportion to its rickety, resource-dependent economy.

The champion of “hybrid” or “grey area” warfare waged from a distance against the West – meddling in elections and stealing secrets with cyber-warfare – Putin can be just as menacing up close. With a surly gaze, controlled mannerisms and a black belt in judo, he exudes an intimidating aura that is capable of reducing his underlings to jelly and has often caught foreign leaders by surprise. Angela Merkel, the German chancellor, discovered his intimidating streak when he unleashed his dog on her during a meeting – he knew that she had been attacked by one years before.

Putin likes to boast about how well he understands the West, claiming he always knows “how they will respond” and calling Britain and America “predictable”, according to a cultural figure close to him. Yet while he has managed to run rings around them, things are more complicated for him at home.

While Moscow and other playgrounds of the elite are filled with designer boutiques and coffee shops, Putin appears to have grown tired of playing the “good tsar” who occasionally turns up in remote villages to give local officials a dressing-down for not looking after the serfs before vanishing into the Kremlin.

The public mood has soured. “In the early stages of Putin, the deal was ‘we will deliver rising living standards and services and you will allow us to stay in power,’” Sawers said. “But that’s become more difficult in the last 10 years because growth has tailed off.”

Russia is what Putin calls a “managed democracy”, meaning that elections are carefully choreographed. The loyal “systemic opposition” competes not to challenge the government but to make it look fair. The penalties for real political opponents can be severe. Navalny has already suffered most of them: he has been banned from political office, arrested, physically attacked and nearly killed.

Putin exerts rigorous control over the security apparatus, but his regime does not have the ruthless efficiency of the Chinese Communist Party, which rules through mass surveillance, highly advanced technology and command of the world’s most energetic economy.

Appalled by what he regards as incursions by NATO and the EU into Russia’s traditional sphere of influence, he likes to blame his country’s woes on the “machinations” of the West and has accused Navalny of being a western intelligence agent. Sawers dismissed this as theatre: “I don’t think it’s in western interests to stir up trouble inside Russia as Putin believes we’re doing – and we’re not doing it. If there was a free election and someone like Navalny came to power we’d say alleluia. But that’s something that has to evolve inside Russia itself.”

It could be a long battle: Putin recently rigged a constitutional referendum to allow him to rule until 2036. Confronted with this increasingly authoritarian 68-year-old, even Russians who like him are beginning to wonder when and how he will ever leave power.

That question apparently began to weigh on Putin himself as far back as 2011. When Muammar Gaddafi, the Libyan dictator, was caught hiding in a drainpipe and killed by rebels just outside his home town, Putin was reported to have spent hours repeatedly watching the video of the killing. “He knows the end will come at some point – and that it might not come very pleasantly,” said a western diplomat with knowledge of Russia.

Anger has grown over the government’s handling of the coronavirus pandemic, focusing attention on Putin’s most glaring vulnerability – his failure to tackle abject poverty in Russia’s vast hinterland. The disintegration of the heartland is not what Putin wants the world to see. But in 2018 I witnessed it in a filthy and dilapidated children’s clinic in the Siberian city of Omsk, where Ksenia Sobchak, a former opposition presidential candidate, pointed at the crumbling walls and said: “Putin does not care about places like this.” (She knows better than most: her father, as mayor of St Petersburg in the 1990s, gave Putin an influence-peddling job the ex-KGB man turned into a stepping stone to power.)

Last August, the region around Omsk erupted in a blaze of protest while Navalny was on a visit to Siberia, hoping to mobilise support for anti-Putin candidates in parliamentary elections this year. He was poisoned with a nerve agent similar to the one used against the defector Sergei Skripal in Salisbury in 2018. After being briefly admitted to hospital in Omsk he was flown to Berlin, where he recovered after 18 days in a coma.

His arrest on returning to Russia did not stop his Anti-Corruption Foundation from releasing the explosive video about Putin’s Black Sea palace. For years Navalny has been exposing corruption, cheekily flying drones over the mansions of the elite, accusing them of living it up while leaving large parts of Russia to rot. The latest video has proved hugely popular and is credited with fuelling public indignation with tales of pounds 500 lavatory brushes.

It also led yesterday to another remarkable development. One of Putin’s old St Petersburg cronies, Arkady Rotenberg, a construction billionaire, claimed ownership of the vast building.

The Sunday Times