Lucy Letby and Grenfell cases show how victimhood can hamper justice

The handling of both shocking cases shows how victimhood can hamper clear-eyed investigation and the path to justice.

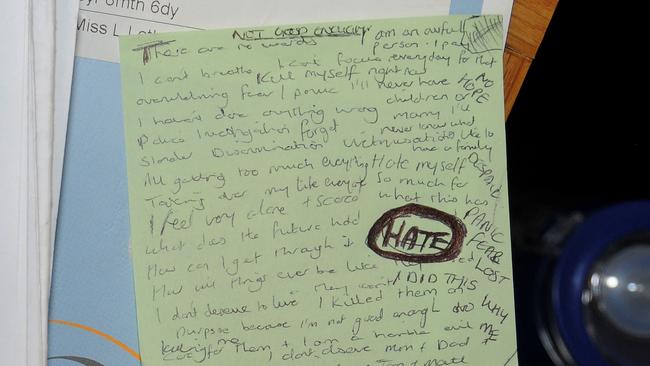

The web of distress and mistrust hangs over us: horror to think of sick babies and a cruel nurse, empathy for parents, unease that deep moral imbalance could hide within a pleasant young woman. Her crazy scribblings of apparent confession appalled us, both at the idea of guilt but also in case they were caused by no more than the terrible pressure of accusation in an unhappy hospital. Again emotion moves us: if Letby is innocent, how cruel are the accusers? We know too much and not enough. We shiver.

More practically we could ask whether jury trial, our bastion of freedom, is wholly fit for such rare cases. Our system is adversarial, not the inquisitorial fact-sifting of the French style. But when a case stirs such deep pity, and a lay jury faces a mass of highly technical evidence, does it serve justice? Counsels’ duty is rhetorically to convince the jury either to condemn or to find “reasonable doubt”, weighing what they were told by barely comprehensible scientists. And to do it while looking at a human being in the dock and hearing families racked by grief.

It cannot help if, as in the Letby case, the tide of emotion flows most fluently in the direction of conviction. Human pain demands closure, certainty, a villain to punish. It may be that some of the passion expressed by Letby’s defenders comes from a sense that the world always wanted her guilty. Naming and convicting a monster makes it easier to move on.

More widely, giving weight to emotion in practical matters is increasingly part of our humane society. Justice is portrayed as blindfolded, not tearfully stretching out a sympathetic hand, but the trend both in courts and inquiries such as Grenfell, Covid or the Post Office has edged towards almost prioritising private suffering.

Victim impact statements are useful in underlining the pain a criminal caused, but victims cannot be judges. A lesser crime might hit very hard on one person whose eloquence brings us to tears, while a more robust or cheerfully fatalistic victim of the same attack or fraud might not find the words to express it. Or even want to: one woman robbed and bruised in a mugging firmly told victim support she wouldn’t do a statement about psychological damage because it would make her feel feebly pitiable. She might have preferred, like that magnificent child at the Rudakubana trial, to say defiantly: “Spend your whole life knowing that we think you’re a coward.”

The Grenfell inquiry was a fascinating, initially frustrating example of this new instinct to put individual grief and damage centre stage before a cool inquisition asking how, when, why? The first year heard evidence from bereaved and sufferers, importantly defining the timeline but also asking for harrowing personal stories in detail - even that of a young man who wasn’t there but was so traumatised by searching for news of his mother that for a while he became convinced, and stated, that he was inside the tower.

I remember feeling both horror and grief at the time but also impatience. I wanted Sir Martin Moore-Bick — an expert in the hard practicalities of commerce and shipping — to be rapidly moving on to detail: who commissioned and who sold which materials? What precaution and regulation failed? When? Why?

He did get there brilliantly, but companies, architects and officials had time to prepare while we listened to sad, timeless stories of private loss and terror. Maybe it had to be that way round; but my outsider’s instinct, as with marine accident reports of ships and yachts, wanted faster focus on “never again!” before reflection on “how frightening, how tragic, how psychologically damaging”.

Move on, far down from the extremes of tragedy and the need to acknowledge it, and everywhere you find the risk that humane respect for feelings is edging away from cool judgment. Sometimes it creates a hierarchy: the government is now contemplating an irrationally specific blasphemy law because of expressed Muslim pain at seeing the Koran burnt.

And in a Scottish tribunal a middle-aged doctor, transitioned to claim femaleness only the year before, pleads feeling “upset and unsafe” and bullied because a nurse in the changing room, menstruating at the time, found a large male-born presence troubling.

Today, ancient pride in stiff endurance is out of style, and victimhood a desirable tool of privilege. Come right down to the ridiculous, and here’s a sacked headmaster claiming “disability” - wholly self-diagnosed - because it affected his golf club role. Well, as a serial sack-ee one knows the feeling all too well.

But it helps to hark back to the disabled, maimed and bereaved Victorian poet WE Henley: “In the fell clutch of circumstance/ I have not winced nor cried aloud./ Under the bludgeonings of chance/ my head is bloody, but unbowed.” None of us can guarantee to follow Invictus, but as an aspiration it does have something to be said for it. And many, even true victims, achieve it.

The Times

Is Lucy Letby a killer, or victim of a grievous miscarriage of justice? We cannot ignore the argument now raging, or avoid asking how well our justice system serves such cases. Sir David Davis MP claims “90 per cent” certainty of her innocence. A distinguished neonatologist leads doctors disputing the evidence, statistical experts offer analysis, supporters demand an appeal. But at the same time the parents of seven dead babies are incandescent. One mother tells the BBC that the families “already have the truth” and that they trust the jury and accuse doubters of a disrespectful “publicity stunt”.