Lucy Letby: Is she a baby killer or a victim of injustice?

There is a growing movement, ranging from credible experts to wild conspiracy theorists, who insist Lucy Letby did not have a fair trial.

Is the infamous British baby killer, Lucy Letby, innocent?

It seems an incredible question to be asking given the neonatal nurse was tried in a court of law, found guilty between two juries of killing seven babies and trying to kill seven others.

Her attempts to appeal have been rejected twice by judges. She is serving 15 whole-life prison sentences.

Yet others see it differently. Letby’s parents and friends maintain her innocence, and there is a growing movement, ranging from credible experts to wild conspiracy theorists, who insist she did not have a fair trial.

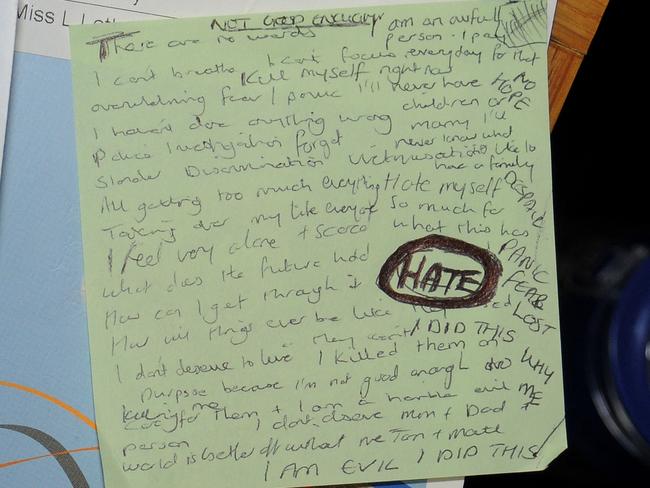

They point to the fact that the prosecution never established Letby’s motive, they point to the lack of smoking-gun evidence and they wonder why a woman who appeared healthy and happy would commit such heinous crimes.

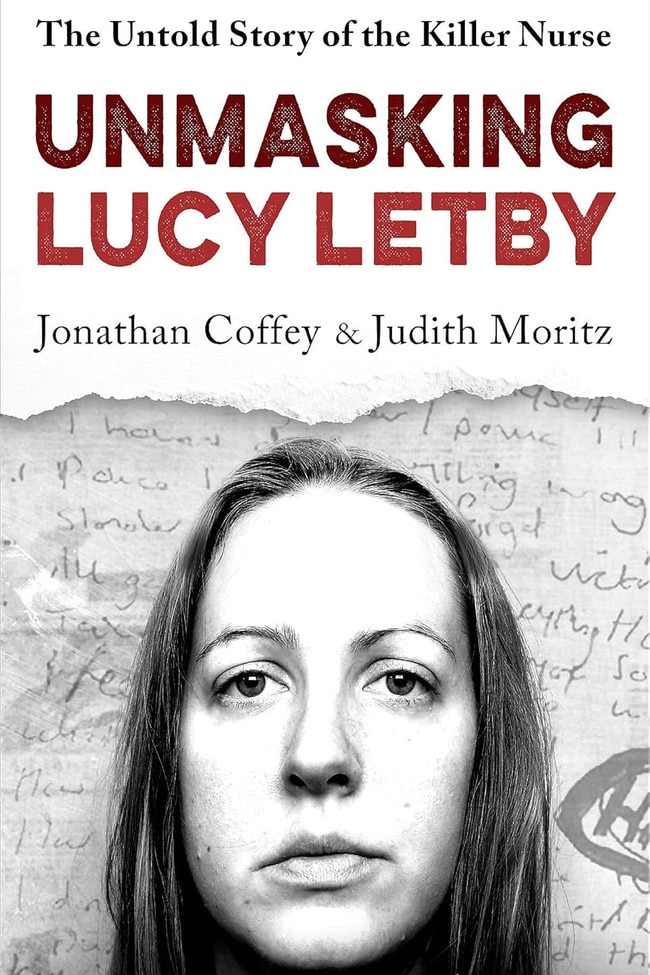

So is Letby Britain’s most prolific child killer or the victim of a grave miscarriage of justice? Who better to ask than Judith Moritz and Jonathan Coffey, the authors of a new book, Unmasking Lucy Letby?

Moritz, 48, is a BBC special correspondent and was one of only four reporters in the courtroom throughout Letby’s trial. She attended the retrial and Letby’s first appeal, and has been reporting on the case since 2017, when police began investigating a spike in deaths at the Countess of Chester Hospital.

Over 25 years she has reported on court cases and inquiries, including those relating to the serial killer GP Harold Shipman and Moors murderer Ian Brady, as well as the legal aftermath of the Hillsborough disaster and the Manchester Arena bombing.

Her co-author and colleague Coffey, 43, has produced and directed dozens of BBC Panorama documentaries. He became involved with the case after the trial began and together they made Lucy Letby: The Nurse Who Killed for the BBC.

We meet on a cold, wet September afternoon at the BBC’s offices in Manchester.

Intriguingly, much like the country at large, they are somewhat divided on the issue of Letby’s guilt. As they write in the book, for Moritz, seeing Letby’s performance in the witness box “felt like confirmation of the prosecution’s case”. Moritz says nothing she has seen or heard since the case has changed that view.

Coffey, however, writes that his concern “that Letby could be innocent trumps all others”. He tells me: “I’ve worried about that every day and night. That’s not to say I’m saying she is (innocent), but it is one of a range of worries that has informed the book.”

The prosecution claimed that all seven babies murdered by Letby had been killed by an injection of air, either into their bloodstream through an IV line or into their stomach through a tube. The babies’ skin had displayed unusual discolouration shortly after they collapsed, something the doctors and nurses had never seen. The prosecution’s expert witness, a retired consultant pediatrician, Dr Dewi Evans, drew on the doctors’ descriptions of the babies’ skin when concluding they had suffered from “air embolisms”.

Evans believes the evidence for the air embolism case is so strong that it’s a fact, and his opinion on the science was accepted as a cause or contributory factor by the jury in five murder verdicts.

However, neonatologist Dr Michael Hall, who advised Letby’s defence team, worries that the evidence is weak and does not meet the threshold of proof beyond reasonable doubt. Hall was never called to give evidence; he does not know why, and Letby and her team have never revealed their reasoning.

For Moritz, the key unanswered questions remain the issue of Letby’s motive, and the defence’s failure to call certain witnesses, including Hall. “Why didn’t you call your experts?” she says. “There were trial tactics, some of which we are still trying to fathom.”

Coffey, who spent three hours in discussion with Hall, adds: “There’s more than one possible answer to that question. Had they called him, he would have made their case worse — that’s what the prosecution experts think. Having spoken to him at length, I’ve struggled to think how he would have made the case worse than it was. He had a lot to say.”

Was it a fair trial if the prosecution called six experts and the defence called none? Moritz comes at this from a different angle. “I’ll tell you what we do know,” she says. “We know that she had four years from the point of arrest to going on trial to prepare with a defence team. She applied for extra funding for a third barrister so that she had the same number of counsel as the prosecution. That team was receiving information from sceptical commentators before (the trial) ... certainly from statisticians. She chose, or they chose, for whatever reason not to air them. We know that there were defence experts, not just Hall, who wrote reports and were lined up.”

These decisions have prompted all manner of questions about the performance of Letby’s defence team. She has hired a new barrister, Mark McDonald, before a fresh attempt to appeal to the Criminal Cases Review Commission. But the experienced barrister Ben Myers KC, who represented Letby in both trials, continues to lead the separate retrial appeal in relation to the death of one baby. “She certainly was happy enough with her defence that she didn’t let them go before the first appeal,” says Moritz.

Moritz puts some of the criticism of the case down to widespread misunderstanding of “the trial process, the legal process, the appeals process. It often feels very reductive. The commentary ... doesn’t take account of the experience of being in the courtroom and watching Letby.”

That experience of observing Letby on a daily basis, which so few people actually had, will never leave Moritz.

“I was surprised by how disconnected, uninterested or unconcerned (she was) with how she would appear. We don’t know what she’s been through but ... I was really surprised at how different to my expectations of an innocent person she looked in her demeanour. Generally she ranged between impassive and distant or kind of dour.”

Moritz says witnessing the prosecution build their case was compelling. “It was like watching it build a house of cards,” she says. “It was a very long exercise in looking at lots of multiple smaller pieces of evidence, which then made a whole.”

The “standout moment” for her was watching Letby give evidence. “That troubled me enormously. A lot of what we’ve seen in recent months has been people raising perfectly understandable questions about the science, or the statistics. But very rarely — I don’t think at all — have I seen somebody talking about what it was like in that windowless, terribly airconditioned courtroom for 10 months, what the jury experienced, what the families experienced, what the journalists experienced.”

Seeing Letby cross-examined over 14 days left a significant impression on Moritz. Her appearance in the witness box was the key opportunity to convince the jury of her innocence. “And that’s what I didn’t see,” says Moritz. “I didn’t see the passion, indignation or the outrage of somebody wrongfully accused.”

Letby did get emotional, but not at the moments Moritz expected. She was tearful when talking about herself, her job, losing her job and when the married doctor with whom she’d exchanged hundreds of Facebook messages came to court to testify against her. “But there were long periods of discussion around what had happened to the babies, which were harrowing for anyone to listen to,” says Moritz. “I don’t remember a moment where that seemed particularly to affect her. Over 10 months, that left an impression.”

In the witness box, Letby would often say she couldn’t recall or didn’t remember events. “She would contradict herself and evidence she previously agreed, she then un-agreed,” says Moritz. “There was a sense that they (the prosecution) had her on the ropes and she had to ask for a break.”

Moritz says Letby often became tangled when responding to straightforward questions related to whether or not she had attacked a child. “That was where she’d tie herself in knots or give politicians’ answers or just try to out-lawyer the prosecutor,” she says.

“There were plenty of moments where she did not come off well. I wouldn’t want to overplay this. It’s one element of a long trial, but it’s significant. I think when the jury retired into the deliberation room and they looked at the evidence that they’d had in front of them, that must have formed a significant part of it.”

Moritz is also mindful of the disservice the post-trial commentary does to the juries. “I watched them throughout that period,” she says of the first jury. “They didn’t return their verdicts in five minutes, without thought.” The jury deliberated for a month and “even when they returned the verdicts, that happened over 10 days”.

Since her first conviction in August 2023, Letby’s case has become something of a national obsession, provoking long, heated debates.

Moritz thinks the fascination can be partially explained by “the disconnect” between the monstrosity of the crimes and the quotidian sweetness of a nurse smiling in pictures.

“Letby doesn’t seem to fit the bill of what you might expect,” she says. “I don’t know what one would expect of a serial murderer of babies, but it doesn’t feel like it’s this.”

Moritz still struggles with the two parallel universes of the case: what she saw in court and the public debate after the trial. “My struggle is with those two not being married,” she says.

Coffey and Moritz acknowledge complete certainty may never be achievable. “What we can say is this,” they write. “For all the imperfections of her prosecution and her trial, the case for Lucy Letby’s innocence is not an easy one to make. If it’s unclear for some that she is definitely guilty, it’s far from clear that she is innocent.”