Tyrants’ worst trait is their claim to virtue

Like the infamous Sacklers and Stalinists, Ghislaine Maxwell says she was doing the world a favour. Somehow, like them, she has convinced herself evil is virtue.

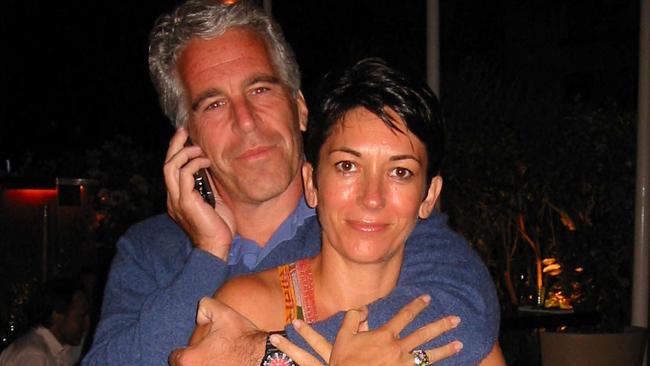

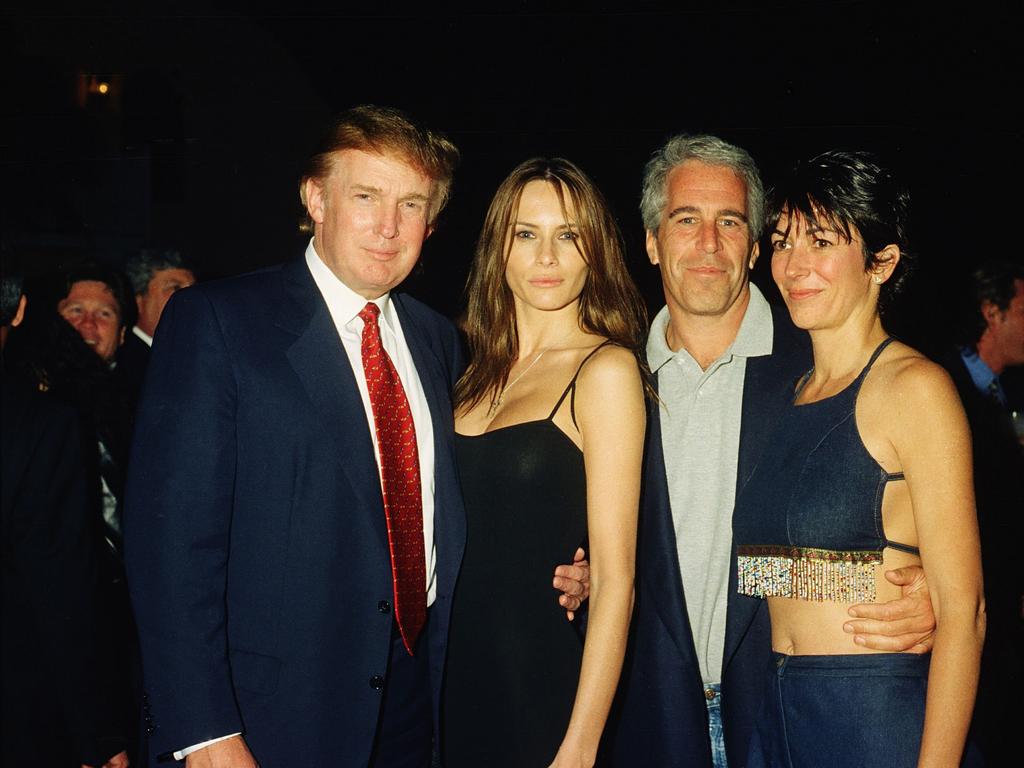

After Ghislaine Maxwell was convicted of sex trafficking, a Vanity Fair journalist, Vicky Ward, published the transcript of an interview with her from 2002.

Ward asked about the allegations by Maria and Annie Farmer that Maxwell and Jeffrey Epstein had sexually abused them. Annie Farmer was one of the four women who testified against Maxwell at her trial.

What’s interesting is Maxwell’s reaction. Over and over again, she expressed incredulity that Ward could be repeating such “outrageous”, “repellent”, “horrible”, “gross”, “disgusting” and “grotesque” claims which were “thoroughly untrue”.

Repeatedly, Maxwell insisted that she never gave massages. Ward was “crazy” to repeat the girls’ claims, and “absolutely nothing untoward in any stretch of the imagination ever took place with them”. “Does it sound remotely plausible?” she demanded.

The Manhattan jury decided that Maxwell was lying. Some may conclude that her outrage over Ward’s article was synthetic and merely revealed her dishonest, manipulative and bullying character.

But there’s another way of reading Maxwell’s behaviour which is darker yet: that she truly believed neither Epstein nor she had done anything wrong. Tellingly, she told Ward: “Every single person who comes to the ranch gets a massage.” But this wasn’t a health spa, and these weren’t the kind of massages you get when a trained individual pummels your muscles to relieve aches and pains. “Massage” was a euphemism for sexualised activity. Yet Maxwell claimed “every single person gets a massage” to convince Ward that nothing untoward had happened. Her apparent belief that no one could raise an eyebrow at such activity suggested that she found nothing wrong with it.

There are echoes of such criminal self-deception in one of the worst medical scandals in American history. The Sacklers, three generations of philanthropists descended from three brothers who were all doctors, became one of America’s richest families with a collective net worth, according to Forbes, of $13 billion. Much of that wealth came from the painkiller OxyContin, marketed by the family business Purdue Pharma. OxyContin is now seen as having initiated a wave of opioid addiction that has led to the deaths of more than 450,000 Americans.

In a 2007 criminal case, Purdue admitted misbranding the drug as safe when it was not. In 2020, it pleaded guilty to conspiring to mislead regulators and paying illegal kickbacks to doctors and others aimed at pushing higher sales.

Carolyn Maloney, chairwoman of the US House of Representatives committee on oversight and reform, said at the time: “At the behest of the Sackler family, Purdue targeted high-volume prescribers to boost sales of OxyContin, ignored and worked around safeguards intended to reduce prescription opioid misuse, and promoted false narratives about their products to steer patients away from safer alternatives and deflect blame toward people struggling with addiction.”

As shown in Patrick Radden Keefe’s book Empire of Pain, the Sacklers originally developed OxyContin to treat pain from cancer. Then they realised there was a vast, untapped market in chronic pain from backs, necks, arthritis and so on.

But OxyContin was an opioid, which the public associated with addiction. To counter this, Purdue argued that its unique properties made it safer than other opioids – a wholly false claim written into the safety leaflet in the drug’s packaging.

Yet throughout, the Sacklers have at best voiced regret but taken no personal responsibility for their actions. Kathe Sackler, who sat on Purdue Pharma’s board from 1990 to 2018, told the committee: “I thought Purdue was acting responsibly to reduce the incidence of abuse and overdose while still serving those in need of pain relief. There’s nothing that I can find that I would have done differently based on what I believed and understood then.”

As Radden Keefe shows, it was hardwired into the family’s mythology that its activities were helping to save lives. So there was nothing wrong with aggressively advertising OxyContin to persuade doctors to prescribe it. Nothing wrong with concealing its addictive properties. Nothing the family did could be wrong because its intentions were noble.

The Sackler and Maxwell scandals illustrate how people can persuade themselves that black is white – including their own motivation. Many tell a story about themselves that is somehow heroic. Thus they stand for decency, compassion, resistance to oppression and so on.

If this clashes with demonstrable realities – including their own venality – they cannot see it. That’s not just because doing so may risk material hardship or a criminal record. It would also destroy their view of themselves as decent people. And few can live with that.

We saw this in the thousands who supported Stalinism, blinding themselves to the evidence of the millions being killed or jailed. We see it now in the fanatical adherence to causes regardless of the evidence – the belief that the West can do no right while the developing world can do no wrong; or that people with male genitalia are women; or that mass vaccination against Covid is worse than the disease. And so on.

There are many reasons why people do or support bad things. But perhaps the most alarming is the hermetically sealed process by which they convince themselves that, when it comes to their own behaviour or views, evil is virtue.

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout