Trumpism will outlast the man

In the end, it didn’t quite come to that. He did warn the leaders that if they didn’t “pay up” by the end of the year, an impossible deadline for vastly increased defence spending, the United States was “just going to do its own thing”. But this ambiguous threat was as far as it went.

At the time, Trump still had advisers trying to hold him back rather than egg him on. And the Dutch prime minister came up with a formula that presented the summit as a triumph for the president, which propitiated him. But it was a narrow escape.

Trump is wildly erratic. Ludicrously vain, absurdly thin-skinned, extraordinarily impulsive. In his first term he sacked senior staff by tweet without telling them first; he appointed people in the same way without getting their agreement; he took against people because they had appeared on television with messy hair; he denied high office to capable people because he didn’t like their skin complexion; he frequently described veterans who had been foolish enough to be imprisoned or wounded as losers rather than heroes; he held grudges because he had seen someone on a daytime television show dissent from his opinion or play down a favoured excuse.

His behaviour towards those he takes a dislike to can remain vindictive for years, while his behaviour towards those he professes to like is capricious. So, as ridiculous as it may sound for the UK’s Ambassdor-designate for the US Peter Mandelson or prime minister Sir Keir Starmer or foreign secretary David Lammy to start praising a president they once assailed, and as obvious as it might be that they haven’t actually changed their minds, they are still acting in the only prudent way they can in the national interest. Could Trump really do something seriously strategically damaging in response to some passing disobliging comment? Absolutely he could.

But while tact and diplomatic behaviour are essential, that is only part of the story. For all that Trump is lamentably unsuited for the office he holds, for all that he doesn’t read his briefing notes and makes eccentric appointments, he isn’t entirely unpredictable. His actions are occasionally hard to forecast but his views are consistent and have been for years. Indeed, on any given issue it would be far easier to guess what the president thinks than to work out the attitude of Starmer.

The problem – a much deeper one than any pettiness or fragile ego – is that these views sharply diverge from Britain’s interests and attitudes and from the basis of our alliance over much of the last 80 years.

Trump does not wish to be “leader of the free world”, a label routinely given to American presidents because of that country’s economic and military power. This is not because he doesn’t wish (and expect) to be the leader in any room he is in, nor because he doesn’t wish free-world countries to follow him. He wants everyone to do that. It is because he doesn’t really believe in the free world at all.

During his last period in office, he unquestionably preferred Turkey’s authoritarian Recep Tayyip Erdogan to Germany’s Angela Merkel, for instance. This wasn’t about mere personal style. That Erdogan was (and is) a so-called strongman was a large part of the attraction.

So Trump diverges from the basic idea that underpins our countries’ relationship – that we are allies together in the defence of liberty against authoritarianism. He also diverges from the view that Europe and America are linked together by informal understanding and formal treaty as friends who show each other loyalty and have a sense of obligation.

This goes beyond his (understandable) demand that European nations pay more for their own defence. He finds the very basis of NATO baffling. When, on taking office on 2017, he was briefed on Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty (the one that says an armed attack on one NATO member is considered an attack on all members), he responded: “You mean if Russia attacked Lithuania, we would go to war with Russia? That’s crazy.”

He also – as is, of course, already apparent – doesn’t believe in free trade. He has for years regarded tariffs as both an economic and political weapon. This is not a whim. It is a consistent and deeply held belief to which he returns often.

More important than Britain appreciating that Trump has strong convictions that can’t entirely be flattered away is appreciating two other things: that there is a large base of support for these convictions in the US and a long history of it.

In his peerless “We shall fight on the beaches” speech, at perhaps the lowest point of British wartime fortunes, Winston Churchill finished with the words “until in God’s good time, the New World, with all its power and might, steps forth to the rescue and the liberation of the old”.

The crucial phrase here is about time, because for long and perilous years it seemed the New World might not step forth.

The war seemed to American public opinion to have little to do with them, and Britain appeared sunk in any case. This “America first” view was so strongly held that President Roosevelt was bound to follow it.

It was only when America itself was directly attacked that it joined the fight. It was, in the end, Japan and Germany that declared war on the US rather than vice-versa.

After the conflict was over, Truman’s White House made a deliberate and conscious decision to recommit to European freedom, against much opposition. Its provision of military and financial support was controversial. It wasn’t some natural and inevitable thing.

Truman was aided in overcoming his critics by the widespread fear of communism and by memories of the wartime generation determined to defend what it had cost them so much in blood and treasure to redeem. But these conditions no longer hold. America was already turning away from Europe under Barack Obama.

Trump’s nationalism is not an aberration – it is the American norm, even if his behaviour can appear abnormal. Our defence and security policy, our trade policy, our expenditure must be readied for a new era in which the US is a much more transactional partner that has less regard to our interests and worldview.

We cannot just shut our eyes and wait four years for Trump to go away. Because when Trump leaves, he won’t necessarily take his worldview with him.

The Times

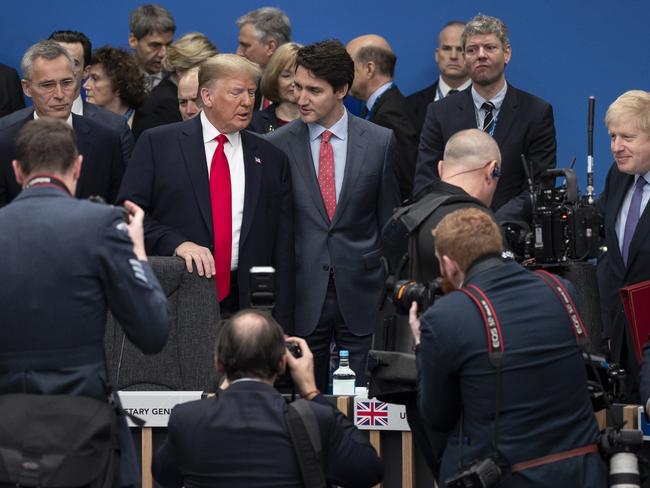

“Hey, get over here. We are about to pull out of NATO.” It was the summer of 2018 and the president’s national security adviser was calling the White House chief of staff. He was alarmed. Donald Trump had been telling him and the secretary of state that “we’re out ... I want to say we’re leaving because we’re very unhappy”. The president was about to go off to the second day of the NATO leaders’ summit and break the news to the allies.