NATO forced to fight a cold war on Baltic seabed amid cables saga

NATO has launched Operation Baltic Sentry on the border of Russia after three underwater cables were severed in the space of two months, harming critical infrastructure.

On a freezing morning in mid-January, a German diver is preparing to jump into the Baltic Sea, a dagger strapped to his wetsuit.

Momentarily exposed to the wind, his hands go pink in the stinging air and his breath steams out of his balaclava. “If you can dive in the Baltic, you can dive anywhere,” he says.

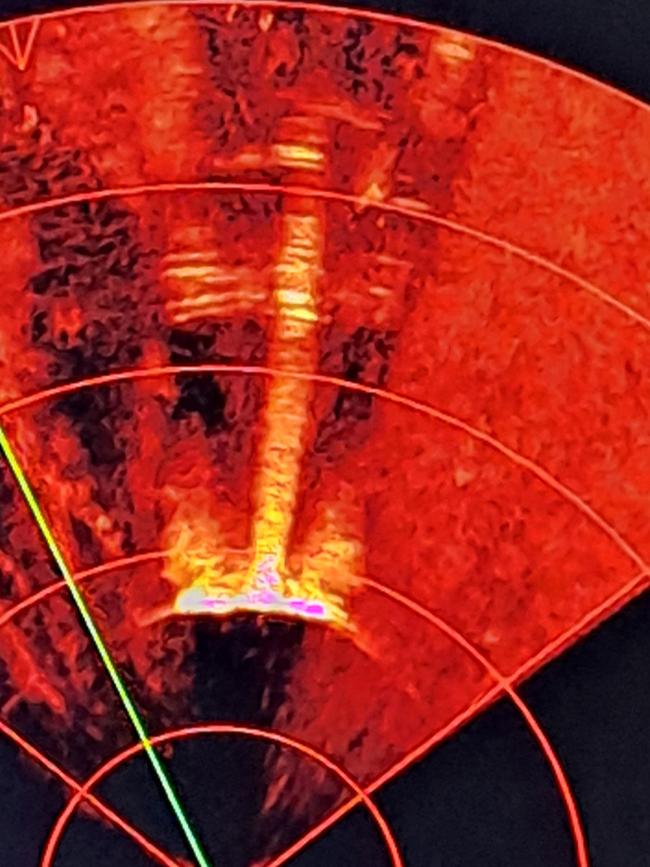

In the Gulf of Finland, elite divers and submersible drones are being sent to the seabed to investigate what appears to be an intensifying campaign of Russian sabotage.

Three underwater cables were severed in the space of two months at the end of last year.

The specialists have arrived as part of Operation Baltic Sentry, a NATO mission to patrol the border with Russia and protect the gas pipelines and internet cables upon which Europe relies.

This week the armada assembled for the first time off the coast of Tallinn, Estonia’s capital, with two F-35s, the most advanced fighter jets in the world, thundering overhead in a display of western military prowess.

The flotilla includes HNLMS Tromp, a Dutch frigate; FGS Datteln, a German minehunter; and HNLMS Luymes, a Dutch survey vessel. More ships, including a Swedish Visby-class corvette and a French minesweeper, are due to arrive.

On Wednesday, Britain announced that it would send P-8 Poseidon submarine-hunting aircraft and Rivet Joint spy planes to bolster the NATO mission in the Baltic Sea.

The announcement came after a Russian spy ship, the Yantar, was tracked by the Royal Navy in the North Sea this week, having been intercepted by a submarine in November as it loitered over critical infrastructure in British waters.

John Healey, the defence secretary, told parliament that the Yantar was being “used for gathering intelligence and mapping the UK’s critical underwater infrastructure”.

He warned President Putin: “We know what you’re doing.”

On the deck of the Datteln, as crew members huddle in the warmth below watching naval films, German mine-clearance divers assess the Baltic chop, awaiting the moment to take the plunge.

They are not at liberty to disclose how deep they can dive, nor can they reveal their names.

“Divers from Mediterranean countries refuse to go down in conditions like these,” says the tallest diver, codenamed 1035. “For us, it’s just a regular day.”

On the bottom, visibility extends just a few centimetres – and a similar murkiness surrounds the recent events in the Baltic. Russia has repeatedly denied responsibility for the attacks on underwater cables.

But patience – already wearing thin after a Chinese container ship admitted “accidentally” shearing the Balticconnector, a gas pipeline, in 2023 – finally snapped with what Finnish authorities believe to be the most brazen incident yet.

At 8.26am on Christmas Day, the Eagle S, a Dubai-owned, Indian-managed and Cook Islands-flagged tanker, sailed directly over the Estlink 2 power cable between Finland and Estonia. Moments later, grid operators reported a power outage.

Given that Estonia is trying to wean itself off Russian gas and is reliant on the pipeline for alternative power, the mishap occurred at a propitious moment for Moscow.

The events leading up to the rupture were also odd. Allegedly part of Russia’s “shadow fleet”, the Eagle S was sailing from the Russian port of Ust-Luga to Turkey carrying 35,000 tonnes of diesel and unleaded petrol.

For reasons unclear, the ship slowed down as it approached the cable and then, according to Finnish authorities, dragged its 11-tonne anchor for 60 miles along the sea floor, eventually severing the power line and damaging a further three cables.

Concluding that the incompetence of the ship’s crew was neither a plausible nor a sufficient excuse for the tens of millions of dollars worth of damage caused, Helsinki responded aggressively.

On Boxing Day, Finnish forces descended on the Eagle S with helicopters and commandeered the 74,000-tonne ship and detained the crew. They argued that the tanker was intercepted in Finland’s exclusive economic zone.

Herman Ljungberg, a Finnish lawyer acting on behalf of the Eagle S, accused Finland of “hijacking” the tanker from international waters in contravention of the law of the seas.

“The Finnish authorities did not have jurisdiction whatsoever to board the vessel and conduct investigations,” Ljungberg told The Times. “It is unnecessary to ask anything about shadow fleets, whatever it means.”

The 24 crew members of the Eagle S were identified as Georgian and Indian nationals and interrogated by Finnish police, with nine ordered to remain in Finland.

A report this week by The Washington Post, citing sources from US and European intelligence, discounted sabotage as the cause of the damage.

The anonymous officials blamed the naivety of the Eagle S’s crew for the accident and gave a similar explanation for another incident involving the Yi Peng 3, the Chinese ship that broke two data cables off Sweden in November.

President Stubb of Finland told Bloomberg TV on Wednesday that sabotage, a mistake and incompetence were all still on the table as possible causes.

However, Finland still has questions.

Why, for example, only a few weeks before allegedly cutting the Estlink 2 cable, did the Eagle S pass back and forth over the Atlantic Crossing 1, a telecommunications cable linking the US to Britain, the Netherlands and Germany.

Allegations have been made that the tanker has a secondary role: as a Russian spy ship.

According to a report by Lloyd’s List, a weekly shipping journal, the tanker dropped “sensor-like devices” into the English Channel during transit last year; transported an unauthorised individual on board; and was loaded with listening equipment.

Finnish authorities denied finding any kit after impounding the vessel.

Ljungberg described the allegation of surveillance equipment as pure conspiracy theory.

“The vessel and its master, which I represent, has not been provided with any information of the investigations. The owners are not suspected of anything,” Ljungberg said.

From the bridge of HNLMS Tromp, the patter of Russian transmissions is heard over the radio as the Dutch frigate probes the shipping lanes in the Gulf of Finland.

As the Dutch sailors scan the horizon with binoculars, Commodore Arjen Warnaar, 60, commander of the NATO flotilla, said of the Estlink 2 attack: “I think it’s pretty naive if you think those cables were broken by mistake … Dragging your anchor over the bottom for miles and miles, that’s not logical is it? If your anchor fell out, you would typically cut your engine, or just cut [the anchor], let it go.”

Mark Rutte, NATO’s secretary-general, warned this week from Helsinki that more shadow tankers could be boarded and crew members arrested if attacks on Europe’s undersea cables did not cease.

But given the legal complications of acting against international shipping – not to mention the risk of escalation with Russia – there appears to be little militarily that NATO can do to retaliate.

The unilateral decision by Finland, NATO’s newest member, to act might have come down to pure economics: the cost of paying potential damages to an international shipping firm for impounding its ship could be cheaper than repairing critical infrastructure on the seabed.

Other defence strategies have been discussed.

General Martin Herem, former head of Estonia’s defence forces, has speculated that NATO could blockade the Baltic. However, given that this would amount to a declaration of war, NATO has opted for a less confrontational approach: surveillance.

“We are the CCTV of the seas,” says Commander Erik Kockx, 51, of the Belgian navy who is involved in Baltic Sentry.

“Anybody who would want to undertake any unlawful action will be seen.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout