Tintin loses sheen as Belgium wrestles with its Congo history

Tintin’s homeland has been struck especially hard by the historical backlash from the Black Lives Matters movement.

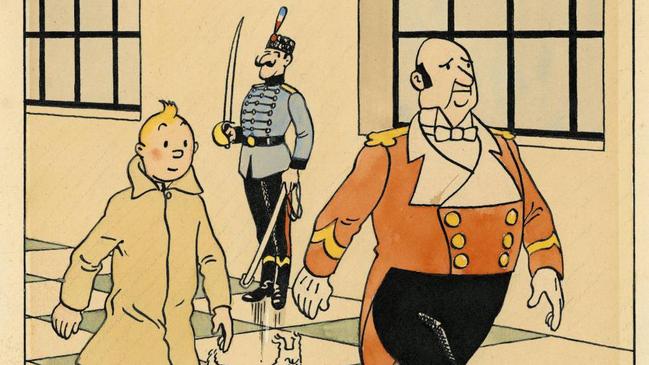

Among the dozens of books by Herge, the celebrated Belgian cartoonist, few provoke such strong feelings as Tintin in the Congo.

The story, first published in 1931, tells of the intrepid boy reporter’s adventures in Belgium’s central African colony. The caricatured indigenous population are child-like and overawed by their white visitor. They talk in a stilted, comic manner.

Tintin’s homeland has been struck especially hard by the historical backlash from the Black Lives Matter movement — and the boy hero is not the only famous Belgian facing uncomfortable questions over his past.

King Leopold II reigned over the country for four decades from 1865 and presided over a brutal colonial regime in the Congo. His statues have been splashed with red paint, set alight or toppled by protesters who see a link between his activities and modern-day racism and police violence.

“It is time for Belgium to come to terms with its colonial past,” said Patrick Dewael, the Flemish Liberal president of the lower house of parliament, last week in calling for the establishment of a “truth and reconciliation” commission along the lines of the body set up in South Africa in the mid-1990s after the end of apartheid.

King Philippe, the present monarch, is being urged to issue a formal apology for the misdeeds of Leopold when the former colony, later known as Zaire and since 1997 as Democratic Republic of Congo, marks its 60th anniversary of independence on June 30. The palace last week declined to comment on the prospect, though royal sources noted any such apology could be issued only after consultation with the government.

Philippe’s younger brother, Laurent, whose foot rarely leaves his mouth, did not help matters with a recent interview in which he said Leopold could not be blamed for any atrocities committed in Congo because he never visited the country.

Tintin is so far safe from such physical depredations — a grand museum to Herge in Louvain-la-Neuve, 40km from Brussels, has yet to be targeted by protesters. Yet the much-loved character risks being seen as an apologist for colonial rule.

“You shouldn’t compare Tintin with Leopold II, but I expect people to start talking about Tintin in the Congo in the current context,” said Philippe Goddin, who wrote his own work last year about the book.

Although some consider it racist, Goddin says Herge, whose real name was Georges Remy, merely reflected the way the Congo was seen by Belgians at the time. “Herge was like a sponge,” he said. “He soaked up the atmosphere and reproduced the mood of the country.”

Tintin treats his Congolese hosts respectfully in the book. Goddin is not sure about Snowy, his talking dog, who accuses them of being lazy. “But just because Milou (as he is known in French) made a couple of such remarks doesn’t make him systematically racist,” he said.

The English edition of Tintin in the Congo carries a warning to modern readers that they may be offended by “bourgeois, paternalistic stereotypes” of Africans. Goddin suspects the French and other editions may follow suit. Legal attempts to ban the book were rejected by a Belgian court in 2012, but there could be more.

The Congo in which Tintin’s adventure is set had been acquired by Leopold with the help of Henry Stanley, the adventurer best known for finding David Livingstone, the missionary. When European powers carved up Africa in 1884, Leopold was allowed to keep it as a personal fiefdom.

More than 80 times the size of Belgium, it swiftly became synonymous with cruelty: local workers who failed to produce enough rubber were mutilated or killed or had their villages burnt down. Campaigners claim as many as 10 million people died, though most historians put the figures at 500,000 to 1.5 million.

Reports of the horrors prompted the emergence in the 1900s of the world’s first international human rights campaign, joined, among others, by Mark Twain, who penned a stinging pamphlet attacking Leopold in 1905. The Congo Free State was also the setting for Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, in turn the inspiration for Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 film Apocalypse Now.

The Belgian government took control of Congo in 1908 and set out to turn it into a model colony, building schools, hospitals and roads. Yet historians say Belgium’s paternalistic attitude prevented the emergence of an educated local elite, setting up after independence decades of mismanagement under corrupt strongmen.

The Sunday Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout