Brewer Colonial must stand up to being ‘branded’

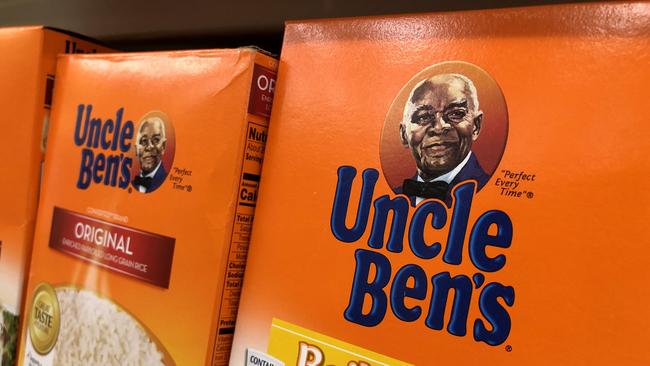

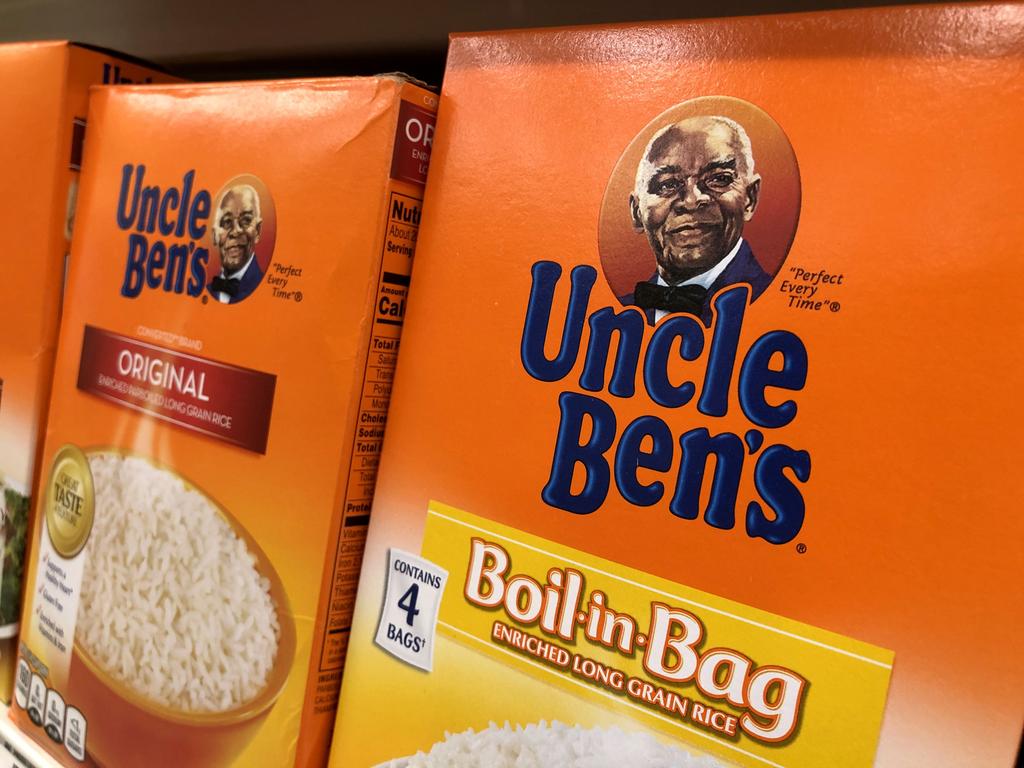

And brands are part of the debate too. Long-established American products are rebranding because their identities and logos are deemed too offensive. Pancake brand Aunt Jemima, which had featured a female slave on its packaging for 130 years, committed last week to changing both the brand’s name and its black titular character. Uncle Ben’s rice, a staple in Australia and the US, also committed to a change of name. Its black servant and use of the honorific term “uncle” are now deemed out of step with modern consumer tastes.

All of which presents the Colonial Brewing Company with a bit of a branding problem of its own. The word colonial brings up unfortunate associations with the past and is strongly linked to the British subjugation of the indigenous people of Australia. The beer company had comments before about its name but things blew up earlier this month when bottle shop Blackhearts & Sparrows decided the removal of the brand would make its stores “a more inclusive place for all”.

The east coast bottle shop is probably less than 1 per cent of Colonial’s off-premises sales. But the move generated a sea of publicity and sparked something of a national debate. At the heart of the matter is an intractable branding issue for Colonial’s managing director, Lawrence Dowd. As he considers his options, he must surely appreciate he is damned whatever he decides to do.

The negative associations of colonialism are only likely to increase in years to come. And if he does not rebrand there is a significant possibility the beer will be loved by the right and rejected by the left. In many ways that process has begun with the brand’s public rejection by a trendy Victorian bottle shop being matched with social media images of Young Liberals downing cans of Colonial on the steps of parliament on Friday.

The rebranding risk

Rebranding is expensive and often goes horribly wrong. And we are not talking about a lone brand of beer that can be quickly rebadged or deleted. Colonial is the corporate name of the brewery, which means everything will need to change and the brand building dial reset to zero. Colonial has picked up a lot of momentum in recent years as one of the fastest-growing, most loved independent craft beers. Any name change would stop the beer in its tracks.

And there are other arguments in favour of Colonial sticking with its name. The verb colonise has two meanings. One describes an attempt to settle and establish control over the indigenous people in an area. The other application describes appropriating a space for use. As I write this, a blackberry bush is very successfully colonising my back paddock.

That second definition is the origin of Colonial’s name. The brewery was founded in 2004 in Margaret River prime wine country. Establishing a craft beer brand in the epicentre of Western Australian wine was the inspiration behind the C word. The name has nothing to do with colonising Australia, which Blackhearts & Sparrows acknowledged when it removed the beer from shelves.

That makes the Colonial brand name very different from the likes of Uncle Ben’s or Aunt Jemima, which really were named from, and inspired by, the subjugation of black people. Colonial is no more offensive than the word Blackhearts, which also has nothing to do with black lives. It was the nickname of the bottle shop’s co-founder, Paul Ghaie. Is his bottleshop in need of a rebrand too?

Of course not. And Colonial should not have to change its name either, especially given the spike in sales this publicity will generate in coming months. The dirty secret of branding is that 80 per cent of the job is achieving salience; marketing speak for coming to mind when someone in a bottleshop buys beer. Just as sales of Corona were boosted by coronavirus, Colonial’s sales are about to go stratospheric.

But negative connotations will remain, and Dowd must tread carefully if he is to enjoy the advantages of his brand’s new-found notoriety while avoiding potential pitfalls. A word on Dowd. He has exhibited near perfect brand management in a situation of great pressure. He has listened to all sides and even understands Blackhearts & Sparrows’ concerns and “feels for them” in the crisis too. He looks to me like a proper leader and exemplifies a practical Aussie even-handedness that contrasts so positively to the mania on display over in America.

Dowd needs to do four things. First, evaluate the situation and (frankly) string this out for as long as he can. Next, come out with a soft-spoken but firm rebuttal of calls to rebrand the brewery. Then use the ability to make small batch sub-branded beer to create a special edition brew and donate the profits to indigenous charities.

Finally, he will know this posturing from white people is almost meaningless compared to tangible responses to the real issue that underpins the Black Lives Matter movement. Colonial needs to set up a scholarship and recruitment drive to give indigenous Australians entry to the fast-growing world of craft beer production.

Black lives do matter. And so do tangible responses. They mean so much more than superficial, inaccurate criticisms of brand names.

The eruption of angst in recent weeks around the Black Lives Matter movement has had a significant impact on a range of things. Broadcasters have slapped race warnings across previously much-loved films. Portraits and sculptures of venerated individuals have been removed from view. And a long, teary line of entertainers has formed from those apologising for sketches once branded funny, now deemed offensive.