Three ways to learn to live with the coronavirus

The Spanish flu is still deadly and with us after a century. We might have to get used to COVID-19 too.

According to most histories, the Spanish flu ended in 1920. The greatest pandemic of the 20th century burnt out and the world moved on.

Most histories are wrong: it did not end, and the virus did not stop killing. Spanish flu’s descendants, in fact, are still with us. Every winter, mutated versions of the 1918 virus still kill. Some years, notably in 1957 and 1968, they shuffle their genes with other viruses and cause mortality in the hundreds of thousands.

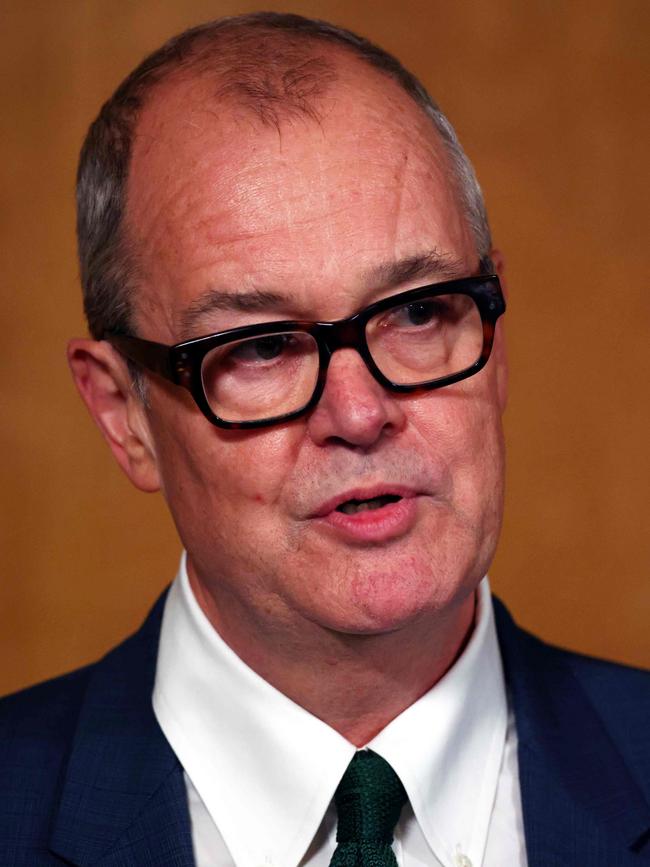

The British government’s chief scientific adviser, Sir Patrick Vallance, says the greatest pandemic of the 21st century will not go away either.

Even with a vaccine we will never eradicate the virus. Instead it will become endemic: part of our lives, along with all the other seasonal circulating viruses. What does that mean?

A virus that conquers the planet rarely just disappears, and that will be as true of coronavirus as it was of Spanish flu. But all viruses are also different, and we are only now trying to assess what living with coronavirus will mean.

REASONABLE BEST-CASE SCENARIO

One day, says Paul Lehner, from Cambridge University, coronavirus could just be an infection you get when young. With the rest of the population safely vaccinated and protected by herd immunity, it may be that “people will be invited to parties — like chickenpox parties — so you don’t get it when you’re older.” Here, they will get a mild cold, more likely an asymptomatic infection, and be set for life.

Of course, Professor Lehner says, when it comes to assessing the future of the virus, “the honest answer is we don’t know”.

We don’t know how long immunity lasts, we don’t know how long symptoms can last. “But,” he says, “I don’t think this virus is so unusual that it is going to make us have to continue to live in the peculiar way we’re living at the moment.”

The famous coronavirus of 2020 could join its anonymous brethren in being merely an annoyance.

Eventually, it may even evolve to lose what teeth it has left. In theory viruses have nothing to gain from a dead host, and all are fated to mutate to become less deadly. In practice, there is little pressure for coronavirus, with a relatively low death rate, to weaken.

There is pressure for it to be better at spreading, though. What is possible is that one strain mutates by chance to become both less deadly and more infectious, and this high-R version outcompetes its low-R rivals to dominate.

It is not unreasonable, Professor Lehner says, to believe we will return to normality. “We have to be optimistic and say that this is the sort of thing our immune system has developed to deal with, and it will deal with this virus.”

MEDIUM CASE

“We will move at some point by some method to some form of herd immunity,” Eleanor Riley, from Edinburgh University, says. It may be through vaccination, it may be through infection. The question is, what does it mean? Not all herd immunities are equal. It’s possible that this can be an illness kept at bay with childhood vaccinations, but it is, she thinks, unlikely.

Jennifer Rohn, from UCL, agrees. “The safest bet is that we will reach a situation similar to what we have with the common cold coronaviruses. These viruses don’t tend to elicit long-lasting immunity — we all get colds every year, after all.”

If reinfections aren’t significantly weaker, our only option is to keep vaccinating: “Given how deadly COVID is compared with the common cold, it will be imperative that we have a mass vaccination program.”

But, without a perfect vaccine, old people will still die. “It could be one of those things we live with in the way we live with flu,” Professor Riley says.

The two are not the same. On the one hand, flu is considerably less deadly. On the other hand it also mutates more rapidly — meaning it is continually evading a vaccine. This is one reason why Spanish flu pops up in different forms.

“If you trade off those two factors, coronavirus may be something that affects the National Health Service in much the same way,” Professor Riley says.

WORST CASE

There are three unknowns, Daniel Davis, from Manchester University, says: treatments, vaccines and the virus itself. Whether or not we return to anything like normal, to a world of socialising, travel and shaking hands, depends on all three.

It is possible that we will have long-lasting immunity, and it is possible that second infections will be weaker. It is also possible that, in some people, the virus will behave completely differently and the reverse will happen.

“There are proven cases of reinfection that have led to worse symptoms a second time around,” says Professor Davis, author of The Beautiful Cure, a book about the immune system.

He thinks it unlikely that the virus is “going to naturally settle down in any way that’s nice for us until we get vaccines and treatments sorted”.

If a vaccine stops 60 per cent of infections, it will be approved. Who will it stop them in, though?

“We already know vaccines work far less well in general for elderly people than young people. If a vaccine works really well in elderly people we may go back to our previous life. What if it works really well in the young but not the old?”

Then, unless we have significantly better drugs to treat it, “Society will have to adjust,” he says. We could be elbow-bumping for a while.

Finally there is one last unknown — what if it is not a disease of the old at all?

“What we have almost no idea about, which could be devastating, is the emerging idea of long COVID,” Professor Davis says.

What if, irrespective of future vaccines and future treatments, the damage has already been done? “The way in which the virus seems to infect people over a very long period of time is potentially a game changer.”

The Times

More Coverage

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout