This is the beginning of Xi’s great unravelling

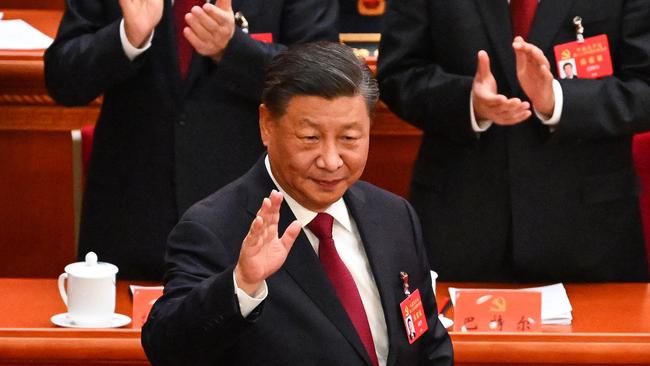

The world’s first techno-autocrat, master of the data universe, is it seems on track with his long-term plans to revive growth and overtake the US, set global rules of trade in China’s favour and keep the Communist Party in power for ever and a day. By Friday, Xi should be elected for a third five-year term; by the weekend the new leadership line-up will be revealed, with only one known certainty: there will be no obvious crown prince. Xi will enter the pantheon alongside the likes of Mao Zedong and the reformer Deng Xiaoping.

Yet this next term for Xi is set to be a moment of hubris. It will be when his authority publicly unravels. When dissent within and outside the party leads to factionalist infighting and an open challenge. When Xi’s guiding credo – that China can never be allowed to fall apart as did Mikhail Gorbachev’s Soviet Union – ceases to persuade a younger, more alert generation. And when the army becomes more assertive, both in Chinese domestic politics and the near abroad.

There have been two distinctive Xi policies over the past decade. The first was to modernise the Communist Party’s drive against poverty. As a teenager, Xi’s communist bigwig father fell out of favour and Xi lived for seven years in a cave in desperately backward rural circumstances. So his commitment to a socialist levelling up wasn’t just ideological claptrap.

In power Xi encouraged the huge, systematic collection of data to feed his surveillance state but he legitimised it by arguing that a country as large and impoverished as China needed to concentrate its data. Facial recognition software and gait analysis – road-tested in Xinjiang province where a million Uighur Muslims have been passed through re-education camps – have revolutionised secret policing. Income disparities have been tracked; social credit scores awarded to citizens on the basis of monitored behaviour.

After Xi ruled that rural poverty had to be drastically reduced, it wasn’t difficult for officials to track down those scrambling for an existence in the countryside. They were ordered to move to cities and offered accommodation – which often, it turned out, didn’t exist.

There have been terrible stories of people stranded between country and city, all the result of local authorities gaming the data to look good. The historian Yuval Harari argues that AI-fed policy-making favours tyrants and social control. In fact, dictators such as Xi can often be misled by biased data since they have no alternative sources of credible information; no checks and balances built into their advice. As China fetishises its data gathering and scoops up private information (abroad as well as at home), so Xi and his small decision-making clique are likely to lose a sense of what is actually happening: the anger that is building, for example, over the stringent Covid-19 lockdowns.

The second Xi error was to turn the anti-corruption campaign – supposed to correct some of the crooked practices that crept in under Deng’s market liberalisation – into a rolling set of purges against often imagined enemy cabals. Xi has been using the amassing of personal power to stamp out crony capitalism and keep the party pure. The result, says Yuen Yuen Ang, author of a sharp-eyed book about China’s robber barons, is the revival of the top-to-bottom command system and the smothering of entrepreneurship.

There’s plenty he could have done to reduce monopoly control of state-owned enterprises. It didn’t happen. Tight control of the economy and the polity, Xi reckons, is the only way to keep the country together, to head off the wild capitalism of the sort that raged in Boris Yeltsin’s Russia. Instead the country suffers from a huge gulf between rich and poor. Ang quotes a Shanghai businessman: “When I was growing up, textbooks tried to convince us about the decadence of capitalism by showing a picture of rich Americans’ pets enjoying airconditioning. Today, my neighbour’s dog will only drink Evian.”

Xi’s solution to these tensions is to censor all public expression so the poor never get to hear about elite lifestyles, and to keep up the threat of corruption trials against self-enriching party bosses.

As a system of control, that can’t survive for long. Reading between the lines of the reports being presented to the party congress, the People’s Liberation Army – always firmly under party control – is being beefed up not only as a fighting force but also as a moral beacon. China should build a strong strategic deterrent, say the working papers; it should prepare for local wars (Taiwan), military academies should be reformed, so should logistics and resource management. Soldiers should be “trained for confrontation”, presumably to make up for the lack of actual combat experience. The army, say Xi’s generals, now has confidence and new capabilities.

The modernisation surge should be complete by 2027; that is at the cusp between Xi’s third and possibly fourth term in office. Here then is the danger zone: Xi, having ensnared himself at home, unable to shake off the sense that China is becoming decadent and stagnant, goes to war as part of a madcap scheme to purify the nation.

– The Times

Everything is in order in Beijing’s Great Hall of the People. Xi Jinping rolled out his pitch to remain China’s paramount leader and the 2300 hand-picked communist delegates applauded thunderously. A solitary dissident who strung two banners across the capital’s Sitong bridge exhorting the Chinese to be citizens not slaves was bundled away. Third-quarter GDP figures, deemed too dismal for public consumption, were withheld indefinitely lest they spoil the party’s mood.