Grave new world recasts light on China conundrum

The war in Europe will leave China in a stronger position, even as it unifies the West. This is something Canberra has largely failed to recognise or, if it has, to respond to creatively.

It’s hard to imagine how bizarre it would have seemed just one year ago for a new Australian prime minister to be making a speech in the Ukrainian capital, Kyiv, or visiting the nearby town of Bucha.

During the past 40 years, a new Australian prime minister would have been expected to visit several major Asian capitals and Washington, if not London, to open their account. Albanese’s first discretionary bilateral visit was Paris, followed by Ukraine. And that was after he was the first Australian leader to attend a NATO summit meeting.

This underscores how much, and how suddenly, the world order has changed, including for Australia, with the return of war to the European continent.

Yet Russia’s invasion is both symptomatic of the changed order and a product of it. Russia did what it did because it could. Moreover, it has not flinched in the face of massive, co-ordinated Western sanctions.

With the rise of China and authoritarian states being more assertive in the face of declining US influence, multipolarity has returned. And the war in Europe will leave China in a stronger position, even as it unifies the West. This is something Canberra has largely failed to recognise or, if it has, to respond to creatively.

Since the mid-2000s, China has been fashioning an order that reflects its weight in the world. But the biggest question was how and where did Russia fit. China is now the dominant power in Central Asia and has been extending this influence across Eurasia. Russia’s brief but effective military intervention in the threatened uprising against the Kazakhstani government in January 2022 shocked Beijing. It showed that Russia was still prepared to intervene in Eurasia, as it had in Georgia in 2008 and Crimea in 2014, regardless of China’s concerns and its principle of noninterference.

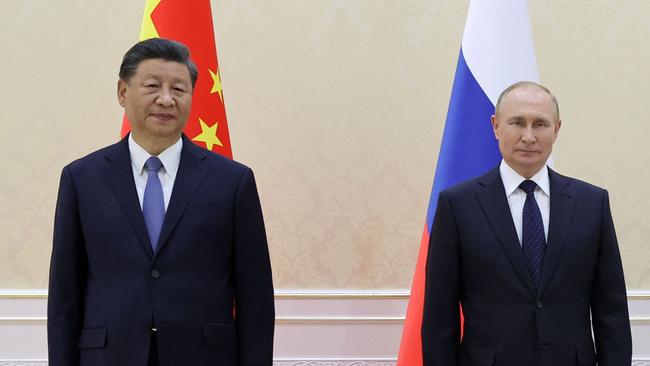

The China-Russia joint statement in February 2022, just 20 days before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, had the flavour of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact of August 1939 – a concert of convenience between two powers that understood that conflict between them would be inevitable.

In the West, the Xi-Putin statement has been widely misinterpreted. The surprise and dismay with which their statement was met overlooks the fact that China and Russia, like Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union, are strategic competitors. Putin was most likely looking to ensure that China would somehow be made complicit to his criminality in Ukraine.

It is also unlikely that Putin confided in Xi on his plans to invade the neighbouring nation.

Their joint statement fits neatly with Xi’s anti-Western narrative, which has become much sharper in the run-up to this year’s crucial 20th Party Congress. The new close relationship with Russia, and the superficial personal rapport between its leaders, would have been seen as a big plus for Xi domestically.

The eye-catching headline statement that the China-Russia friendship knew “no limits” was presented in China as a great diplomatic achievement for Xi. It meant the existential threat that Russia has always posed to China had been postponed to the indefinite future, allowing China more time to consolidate and extend its dominance over Central Asia and ultimately its power over Russia.

That was until February 24. The invasion was a disaster for Xi. China was forced to choose between its newly minted special relationship with Russia and the cornerstone of its foreign policy, non-interference.

To complicate matters further, China also had a rare security pact with Ukraine and a special relationship with Kyiv, with substantial commercial underpinnings. Xi’s failure to condemn the invasion unequivocally also brought China into direct conflict with a more united and purposeful West.

Xi’s flirtation with Putin, and their shared anti-Western stance, meant that China missed a historic opportunity to reset relations with the West post-Trump and post the first wave of Covid. Although Xi’s stance appealed to populist sentiment in China, many in China’s political elite would have seen this as a major miscalculation. By not criticising Russia’s invasion, Xi aligned China with a renegade state. The elites in Beijing view China as being better than that.

Xi’s tacit support of Putin brings to the fore deep tension in China’s domestic politics. While the anti-Western narrative plays out well for emphasising China’s material success, independence and – most importantly – the respect it has earnt, when it comes to the advanced countries of the world, China also wants to be seen as first among equals.

Xi, like Putin, would have been alarmed at the solidarity, sense of purpose and determination the West found following the invasion.

European states had long accommodated Putin’s malicious behaviour, from poisoning adversaries on foreign soil, to Russia’s aggression in Georgia, Crimea and eastern Ukraine. And as Putin was amassing troops on the Ukraine border, the West was acrimoniously at odds over the Afghanistan debacle.

The speed, co-ordination and forcefulness of the West’s response would have reminded Xi, if any was necessary, of China’s own vulnerabilities to coordinated action by the West. The energy and financial sanctions demonstrated that the West was prepared to bear substantial costs in defence of basic international norms.

For China’s leadership, this is especially alarming as it is much more deeply integrated in the international economic system than Russia, from trade and investment flows, holding of foreign government bonds, integration of global supply chains, to elite family fortunes stashed overseas, families resident in the West, reliance on Western education and research, and much more. Unlike Russia, China also faces a significant strategic vulnerability. Among other things, it is the world’s biggest importer of crude oil, liquefied natural gas and iron ore. Most of this is shipped via the Strait of Malacca – one of the world’s most vulnerable transport choke points – and the South China Sea.

A concerted effort by the West to block these transport routes would, in a heartbeat, deny China access to the raw materials and energy it needs and bring its economy to its knees.

So, China’s failure to condemn the invasion of Ukraine, and the West’s preparedness to act collectively, presents China with massive risks and dangers.

Already the US has begun to identify and punish Chinese firms that are found to be contributing, albeit indirectly, to Russia’s war effort.

At its Madrid summit – where NATO classified China as a strategic challenge to its security and values – it was careful to distinguish China from Russia by not naming it as an adversary. However, NATO now believes it has entered an era of competition with China over nuclear arms build-up, and China’s bullying of its neighbours, including Taiwan.

Beijing will also be paying close attention to what all this means for any military strike it might launch against Taiwan. While the war in Ukraine is ongoing and its resolution unknown, Russia’s efforts to occupy and subdue a contingent independent territory highlight the extreme difficulty of the task. The likelihood of victory would be much lower in China’s case with a sea of some 160km separating it from its target.

While Putin’s threat of first strike use of nuclear weapons may be seen in Beijing as having been successful in staving off direct intervention by NATO, China is much too exposed to Western trade blockades and other sanctions to resort to the military option. Put simply, the costs to China are far too high and the war in Ukraine has shown that such actions can stiffen the West’s resolve.

With closer apparent relations between Russia and China, a school of thought – which has found support in the White House – has emerged that there is a single theatre of strategic competition: liberal democracies versus autocracies. It is easy to see the appeal of this formulation, in its simplicity. But viewing the world order as a struggle between might and right, without acknowledging the nuances and subtleties between different countries, runs the risk of increasing the chances of conflict.

It has taken the invasion of Ukraine for policymakers and commentators to take seriously the extent to which the world order has changed. Forty UN members either voted against or abstained on the resolution of March 2 condemning Russia’s invasion. Among those that abstained were India and China.

Since 2017, if not earlier, Australia has ever more closely aligned itself with the United States in the US’s struggle with China to retain global dominance.

For this, Australia has been rewarded by the US through deeper interoperability between the armed forces, intelligence sharing and the promise of nuclear-powered submarines under the AUKUS arrangement.

Senior policy advisers to the Labor government persist with applying the balm that China has changed, not Australia, and that until China becomes more like us, the current state of the relationship is preferable.

Without Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Canberra and Beijing may have been able to find some greater accommodation of each other’s positions. China had an opportunity to reset relations with the West, including Australia, had it condemned the invasion. It chose not to do so. The shape of the new world order is rapidly becoming manifest.

In this new order, Australia must make its peace with China. Of course, this must be on terms that do not compromise Australia’s interests. Australia needs to decide if its foreign and security policies will continue to be based on siding with the US in its rivalry with China, or whether it will recognise the reality of Chinese power and influence in the region and seek ways to work with China to promote stability and peace. Australia has foreign policy options other than the US-China binary. It is time for these to be explored.

The challenge for Australian foreign and security policy is to deal with the world as it is, not as we might wish it to be. This will require a return not only to a central role for an elevated diplomatic effort, but investment in the skills that underpin that, including language, history and cultural studies. If the past year has taught us anything, it is that in international affairs there is no sensible centre, just interests and power, egos and ambition.

The future agenda for Australia is big and urgent.

Geoff Raby was Australian Ambassador to China from 2007-2011. This is an edited extract from his essay in the latest issue of Australian Foreign Affairs out Monday.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout