‘There’ll never be another Camelot’: Kennedy dream dies all over again

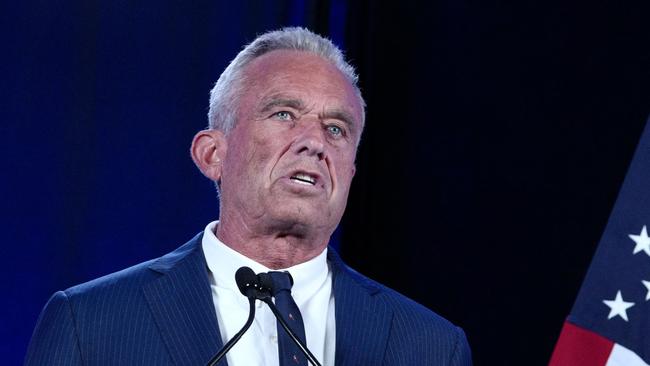

Eccentric White House bid by Robert F. Kennedy’s son recalls the family’s most compelling standard-bearer and the tragedy of 1968.

Even though no serious observer thought Robert F Kennedy Jr stood any chance of winning the US presidential election, the end of his eccentric independent campaign surely brings down the curtain for good on the political psychodrama of the Kennedy dynasty.

The dream of seeing a Kennedy back in the White House dates to the immediate aftermath of the dreadful moment on November 22, 1963, when the newsreader Walter Cronkite announced the 35th president’s death to a stunned nation.

“Don’t let it be forgot,” the widowed Jacqueline Kennedy told an interviewer a few days later, quoting her husband’s favourite musical, “that once there was a spot, for one brief, shining moment, that was known as Camelot. There will be great presidents again … but there’ll never be another Camelot.”

For Kennedy devotees, however, the dream of rebuilding Camelot never disappeared. Many pinned their hopes on the late president’s youngest brother Ted, who combined a playboy lifestyle with an impressive legislative record.

Representing Massachusetts in the Senate for 46 years, Ted Kennedy was instrumental in passing countless laws covering everything from civil rights to children’s healthcare. In his political prime in the 1970s and 1980s, he was seen as the great hope of liberalism, a progressive voice in an increasingly conservative age.

Alas, there were always two sides to the Kennedy mystique. For all his rhetorical power and passion, he never escaped the shadow of the Chappaquiddick incident in 1969, when he left a party on Martha’s Vineyard with the 28-year-old Mary Jo Kopechne, crashed his car into a tidal channel and fled the scene in the dead of night, abandoning his passenger to drown.

For anybody else, lacking the magic surname, this would surely have meant political extinction. Somehow Kennedy managed to cling on to his Senate seat. But after Chappaquiddick, his chances of the Democratic presidential nomination, once a near certainty, were crippled for ever.

Even 11 years later, competing for the nomination with the hapless Jimmy Carter, Kennedy never banished the shame of that terrible night on Chappaquiddick Island. As he toured the country in the spring of 1980, hecklers shouted: “Where’s Mary Jo?” And though he bowed out at the Democratic convention with one of the most rousing speeches in modern US history ("The cause endures, the hope still lives and the dream shall never die!”), he only had himself to blame.

For me, by far the most compelling of the dynasty’s lost standard-bearers was the original Robert F. Kennedy, father of the anti-vaccine maverick who is set to throw in his lot with Donald Trump.

Born in 1925, Robert had begun his political career as his brother Jack’s chief lieutenant. They were the perfect partnership: the dashing charmer and the ruthless fixer. And even as a youthful attorney-general, Robert seemed little more than his brother’s creature, an uncompromising foe of organised crime and a very grudging friend of civil rights.

When Jack was shot in 1963, Robert sank into a deep depression. And as he entered his forties, he underwent a genuine personal transformation, spending hours reading Greek tragedies and leading a team of climbers to scale Canada’s Mount Kennedy, then the highest unconquered peak in North America. He visited South Africa to meet anti-apartheid campaigners, founded a slum regeneration project in Brooklyn and travelled to the Mississippi Delta to see its poverty at first hand. Perhaps most shockingly for people who remembered the crew-cut enforcer of old, he even grew his hair.

By the time Robert entered the presidential race in March 1968, his image had changed completely. Campaigning in his shirt-sleeves, his hair tousled, his reedy voice burning with passion, he presented himself as the champion of the poor and the young, a voice for downtrodden African-Americans and Mexican migrant workers. To voters who preferred his brother’s cool, clipped moderation, it seemed a disconcerting reinvention, and definitive proof that the centre ground was collapsing beneath their feet. But few candidates in American history have ever inspired such enthusiasm among their young activists.

At his earnest best, Robert was a genuinely electrifying figure. Even today, when you listen to his improvised words to black supporters in Indianapolis after Martin Luther King’s murder, you can feel the shivers down your spine. Again and again he implores them not to react “with hatred and mistrust” and urges them to “make gentle the life of this world”. At one point he quotes his favourite line from Aeschylus: “Even in our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart, until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God.” You wouldn’t get that from a presidential candidate today.

Would Robert Kennedy have won the presidency had he lived? Perhaps not. In a year of extraordinary turmoil, marked by campus violence and race riots, many Middle Americans saw him as the embodiment of disorder rather than the answer to it. And even if he had won the Democratic nomination, he would probably have struggled to match Richard Nixon’s law-and-order message in the general election.

But we will never know. For as he was leaving the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles, just moments after winning the crucial California primary, he was shot three times at close range by a young Palestinian, Sirhan Sirhan, who blamed him for Israel’s victory in the Six-Day War. With those fatal shots, the best hope for a Kennedy restoration was extinguished for ever.

Even today, many liberal activists believe that Robert Kennedy’s assassination marked a turning point in political history, closing off a lost road to the sunlit uplands of national unity. That’s almost certainly a utopian fantasy. In an increasingly populist age, the Kennedy brothers’ brand of politics was becoming rapidly outdated; even in 1968, it was clear that the future belonged to the right.

But in America, a land of the imagination, there will always be a place for idealistic daydreams. And when you look at the state of the union today, can you really blame the Kennedy loyalists for looking back and wondering what might have been?

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout