There may be too much California in Kamala

California was the home state and political base of important right-wing leaders, of Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan as well as Schwarzenegger. In the late 1970s it was the home, too, of America’s revolt against taxation, passing Proposition 13, a tax-limiting amendment to its constitution, with more than 60 per cent of the vote. It remains the home of influential Silicon Valley libertarians who fund and encourage right-wing candidates.

But for the foreseeable future California will not be the home of an emerging conservative leader. There will be no more Reagans and Nixons for decades to come, if ever. That is one of the most important things to understand about this year’s United States presidential election.

Over the past 20 years, the politics of California has changed sharply. As Schwarzenegger was trying, without much success, to explain to his party, Republican positions are no longer winning ones there. As one of the leading political reporters in the state, Dan Morain, puts it, they are “out of step with California voters on gun control, the environment, abortion, same-sex marriage and, especially, immigration”.

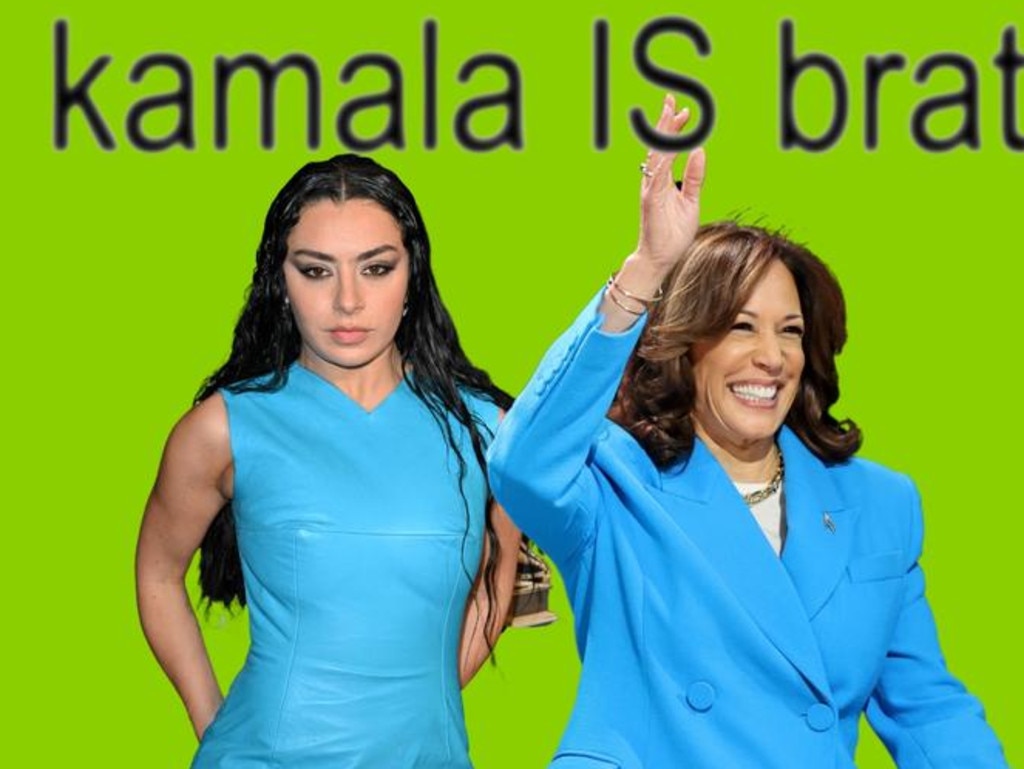

He used these words in his useful account of the life and career of one of the leading politicians to emerge from California’s new politics. Kamala’s Way is a study of how the vice-president and Democratic Party nominee Kamala Harris rose through state offices to become California’s junior senator and a candidate for national office.

Considering the way she has navigated California’s changed political terrain is essential to assessing her prospects in the scarily close run-off with Donald Trump.

California’s politics has been changed over the past 20 years by two things: immigration and emigration. In 1994, the governor, Pete Wilson, then and for many years afterwards the most influential Republican in the state, supported an initiative to deny undocumented immigrants access to all government-funded services. It was a short-term political winner for him. But it soon became a political disaster for the party.

By 2010 California had long reached the immigration tipping point (Latinos now make up almost 40 per cent of the population) where anti-immigrant policies became seen as an attack on residents rather than a protection for them. Now, fewer than 25 per cent of voters are registered Republicans. And while immigrants were moving into California, other people were moving out. Having long been the place to which Americans from other states moved, the state has become somewhere they move from. This emigration has been of both white and Latino voters, but disproportionately the leavers have been people without college degrees, unable to afford the more expensive cities in the state. So California politics has become dominated by the interests of two of the core Democratic groups of voters: new ethnic minority immigrants and highly educated, well-off people.

Harris has shown great skill at appealing to these audiences. By the time she ran to become senator she was such a strong candidate it was obvious almost from the outset that she would win. She had one serious rival in the state (the governor, Gavin Newsom) but has even outrun him with a combination of luck and judgment. When she acquired enemies, they were not ones that really moved the political dial in California. She fell out with the police union, for instance, after refusing, as district attorney, to pursue the death penalty over the murder of a police officer, Isaac Espinoza. But it didn’t halt her rise.

This suggests a politician of rare ability, showing as a prosecutor and the state’s attorney-general a knack for picking issues that appealed to core audiences (her stands against banks and for-profit colleges and for victims of human traffickers); for collecting important allies (the man who ran the Democratic machine, Willie Brown, remained her booster long after being her boyfriend and she formed an early political alliance with a young Barack Obama); and taking the edge off any jealousy her ambition might incite by showing plenty of warmth, empathy and charisma. To rise to the top of the overwhelmingly dominant political party in a state as large as California is undeniably impressive. So why, when I spoke to one senior Obama-era adviser about her before Joe Biden withdrew, was he so sceptical about her chances in the national race? Because California isn’t typical.

The white working-class people who moved out of California’s major cities because they couldn’t afford them any more didn’t disappear. They moved to other states, places like Texas, where they inhabit more conservative, often lower-taxed suburbs, and do their voting there.

In her career in California state politics Harris hasn’t had to appeal to these people or anyone much like them. When she ran for president in 2020 she began as what was known as a top-tier candidate – in other words, one of the favourites. She did so poorly that she had to withdraw before the first contest, before the caucus in Iowa, because a floundering performance had left her campaign without any money.

Her main weakness was having little by way of a broader message and only an appeal to the party’s more liberal supporters. A failure to say anything of substance began to irritate funders and pundits and the problem soon became a crisis for her campaign. Has she now put this right?

Harris’s speech to the convention last week showed all the skills – the charisma, ambition, political toughness – that got her to this point. The delivery and political aggression attracted, justly I think, reviews that ranged between “competent” and “brilliant”. The latter was the verdict of the electoral statistician Nate Silver, whose judgment I take particularly seriously.

But I still wondered whether there was enough for the voters beyond California. Enough for voters allergic to high taxes, worried about price fixing (an eccentric Harris proposal) and alienated by the “woke” ideology? There is no point building up support in the big cities and liberal states and losing, in the electoral college, the places to which the California migrants have fled. This was the fate of Hillary Clinton and it looms over Harris, too.

For those, like me, who believe that the return of Donald Trump represents perhaps the most serious threat to the democratic West in our lifetime, the charisma and vigour of Harris as the Democratic candidate has come as a relief. The winning mentality of the Californian provides hope. But California itself remains a worry.

The Times

“In movie terms, we are dying at the box office. We are not filling the seats.” In 2007 Arnold Schwarzenegger addressed these words to the Republican Party in California at a convention in the desert resort town of Indian Wells. He was trying to get his audience to understand why, as Republican governor, he had moved to the centre to win re-election. He was heard in complete silence.