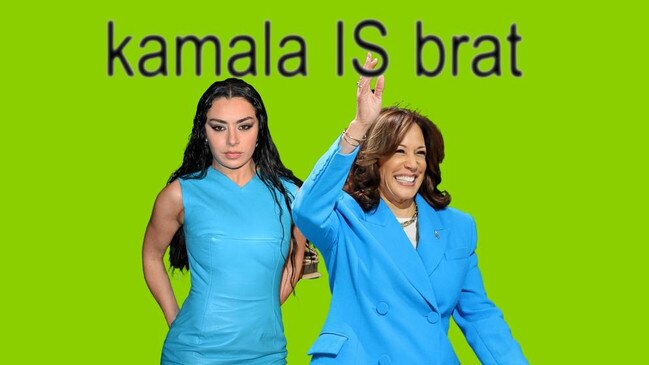

Kamala Harris has been adept at translating her campaign to the TikTok phenomenon

The Harris campaign has been assisted mightily by being showcased as part of ‘brat summer’ by a virally successful musician known as Charli XCX.

The earliest televised presidential interview occurred in 1940 with a very relaxed president Franklin D. Roosevelt taking questions before the camera. Impeccably dressed, Roosevelt showed no sign of his infirmity but every sign of presidential confidence with the new medium.

While it may not have been recognised until September 1960 in Chicago, with the first televised debate of a presidential election year between Massachusetts Democrat senator John F. Kennedy and California Republican vice-president Richard Nixon, television was an early entrant into the means of communication in 20th-century American politics.

For FDR, care and attention to the media of the day was a principal tool in winning heartland support for his administration and policies. This can be seen in the record of his presidential press conferences, where he often joked with the press about major announcements, such as sending Harry Hopkins to wartime London. First lady Eleanor Roosevelt made a primary contribution to the administration’s success by holding a total of 348 press conferences aimed at the female members of the Washington press corps.

But it was the fireside chats on radio between March 1933 and June 1944 that enabled FDR to dominate US politics through the Depression era and into the challenges of World War II.

The fireside chats took Roosevelt from the White House to a vast audience of people in their living rooms. By 1941 the audience could number 54 million people, of roughly 82 million American adults at the time.

But the more important feature was that Roosevelt spoke directly to Americans without the filter of reporters or analysis of opinions. This is the salient feature that separates all the most effective tools of presidential communication from the alternatives.

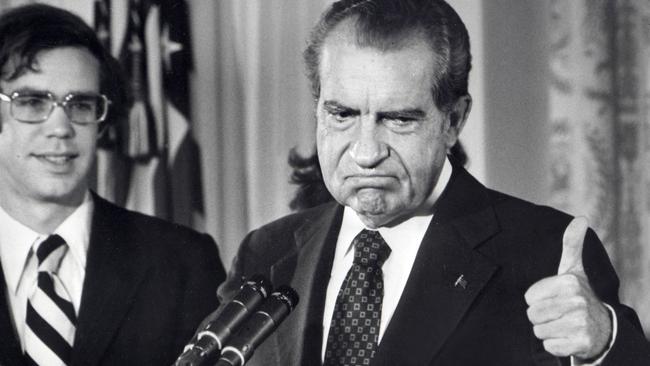

All American presidents endeavour to master the media. Many struggle, although few fail as woefully as Nixon. This is somewhat surprising given it was Nixon’s foray into TV in 1952, in the form of his “Checkers” speech, that saved him from being dropped from the Republican vice-presidential nomination by General Dwight D. Eisenhower later that year.

This success was forgotten in Nixon’s White House years when, under pressure, he forbade his officials from talking to several major publications, including The New York Times and The Washington Post, because of their opposition to his administration. But tension between the White House and the Washington press corps has a long and recurring history.

Indeed, the existence of the White House Correspondents’ Association is to be found in a protracted dispute beginning in 1913 between president Woodrow Wilson and the White House press. Wilson was aggrieved with the coverage by several newspapers, and some of the people attending his press conferences were not even accredited journalists, so Wilson threatened to ban all press briefings. The White House Correspondents’ Association, renowned for hosting annual dinners, was the response.

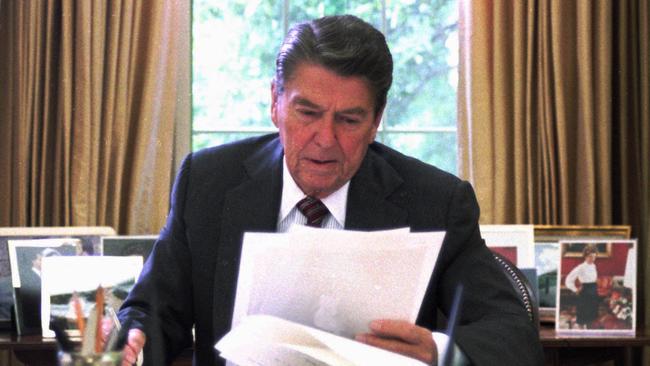

Perhaps the best observation at the White House Correspondents’ annual dinner was offered in 1988 by president Ronald Reagan, detailed in his book Speaking My Mind. Reagan suggested the most accurate summation of his relationship with the press could be contained in: “He gave as good as he got.”

But Reagan was an actor. He translated his somewhat modest theatrical skills into a presidential career. He was a television president following in the footsteps of Kennedy in this regard.

The first Kennedy-Nixon debate on September 26, 1960 in Chicago was one of the most influential television episodes of American presidential politics, at least until the Joe Biden-Donald Trump debate of June this year.

Kennedy understood TV and his appearance, fresh from the Kennedy family compound in Florida, was contrasted with Nixon’s haggard appearance. Nixon had promised to campaign in all 50 states and was endeavouring to honour the pledge, resulting in a degree of exhaustion. This meant that Nixon’s appearance, with a five o’clock shadow dominating his jowls, was anathema to the television camera.

Famously, that morning in Chicago a Nixon aide endeavoured to disguise the candidate’s appearance with Lazy Shave powder; it did not work. Lazy Shave is still on exhibition at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC. In fact, so gaunt did Nixon appear that legendary Democrat mayor of Chicago Richard J. Daley quipped: “My god, they’ve embalmed him before he even died.”

In office, Kennedy demonstrated his appreciation of the television medium by delivering major announcements to the American people directly from the Oval Office. The blockade of Fidel Castro’s Cuba in October 1962 is perhaps the best example.

The 2024 campaign for US president is dominated by different media. A friend said to me recently that Kamala Harris could well be the first “TikTok president of the United States”, and Harris has been adept at translating her campaign to the phenomenon.

Donald J. Trump certainly followed Barack Obama as a so-called Twitter president, but TikTok could be decisive in young Americans deciding if they will vote, and for whom they will vote. Rebuilding the Biden coalition involves 18-year-olds as well as any other demographic.

The Harris campaign has been assisted mightily by being showcased as part of “brat summer” by a virally successful musician known as Charli XCX.

Again, and it is worth mentioning, the beauty of TikTok for a political campaigner is that it is direct communication with the voters in the tradition of the fireside chats and the Oval Office announcement.

Trump has not ignored the emerging social media. Podcasts have become a preferred way of getting his message out. Technical difficulties aside, Trump’s interview with Elon Musk has set a new benchmark for X, formerly Twitter, to be part of all future campaigns, depending on whether the owner acts as a censor.

The Tesla connection continues in an odd way, with one podcaster offering the Republican nominee a Cybertruck, which potentially may have run afoul of US campaign finance rules. But it does break new ground, like Trump’s offer of a cabinet position to Musk in a potential second Trump administration.

The television presidents, particularly Kennedy, Reagan and Obama, went so far as to curate the backdrops for their appearances. Among the more successful efforts may be Reagan in 1984 in Normandy, and both Kennedy and Obama, of different generations, before the same iconic structure of the Brandenburg Gate in Berlin.

The visuals drove the candidate’s theme, thus reinforcing Marshall McLuhan’s famous nostrum in Understanding Media (1964) to the effect that: “The medium is the message.”

If McLuhan were writing the same book today, the theme of this Canadian visionary almost certainly would be: “The meme is the message.”

Stephen Loosley is a former chairman of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, Canberra.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout