The men Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping are really afraid of

Lai’s fate should concern us all. Not only because he is a British citizen. Not only because it reflects on the way that Britain was duped by China over the return of Hong Kong. But also because, day by day, Beijing is making clear that whatever glowing future it envisages for China will always depend on the mechanisms and entrapments of a police state.

Lai is a free spirit and, as such, a threat to Xi Jinping’s regime. He arrived in Hong Kong by boat at the age of 12, a stowaway from the mainland, became a child labourer in a textile factory and rose to become its manager. Using a bonus, and with some chutzpah, he bought a bankrupt factory, founded his own profitable garments outlet and expanded into grocery stores.

The 1989 massacre in Tiananmen Square shaped his politics. He read Friedrich Hayek’s The Road to Serfdom (Margaret Thatcher’s favourite read) and started to buy up magazines. His most open challenge to the regime was to start the Apple Daily and turn it into a blunt, easy-to-read, British-style tabloid. “Drop Dead!” was the exhortation in one of his columns, directed at the Chinese premier Li Peng, known as the “Butcher of Beijing” for his role in ordering the Tiananmen crackdown. The communist party, Lai wrote in another piece, was “a monopoly that charges a premium for lousy service”.

Inevitably Lai became a target. When he sided with Hong Kong demonstrators he was peppered with death threats, his car rammed, his home fire bombed. The question for the Chinese regime was clear: how far can wealth and influence provide a shield of immunity? The handover of Hong Kong, the erosion of its supposed autonomy, the ascension of Xi and his henchmen, all provided an answer of sorts. Entrepreneurial modernisers, in so far as they promoted an open society, had to express public loyalty to communist rule or risk losing their fortunes. The internet billionaire Jack Ma criticised the role of financial regulators and found himself disciplined by Xi, almost disappearing from view. He and other tycoons are back now, though somewhat poorer and much more discreet.

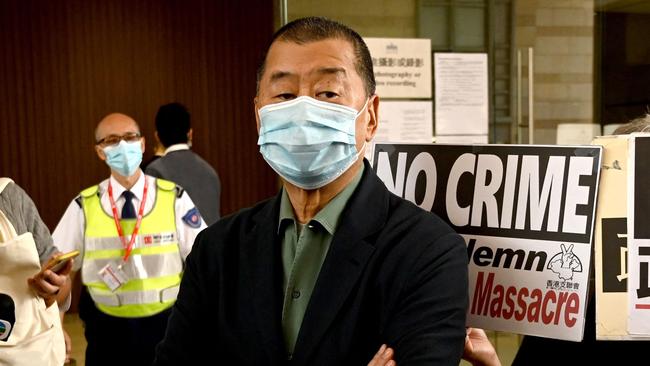

Lai was never even close to matching Ma’s fortune so it was easier for the regime to lock him up. This week’s appeal saw him cleared of “organising” protest demonstrations but not of participation in 2019. He is now serving out sham fraud charges and awaiting a further trial for alleged sedition and breaches of the menacing National Security Law.

It is a similar predicament to that faced in Russia by Mikhail Khodorkovsky. Now aged 60 and living in exile, he was once rated the wealthiest man in Russia, having amassed a fortune of $15 billion. He profited from privatisation, took control of a number of Siberian oil fields and was associated with government modernisers. But in 2001 he also founded “Open Russia”, with the ambition of strengthening civil society. In essence he made himself into a potential political challenger. Putin took note and in 2005 he was jailed for nine years. His fortune shrank, his sentence extended.

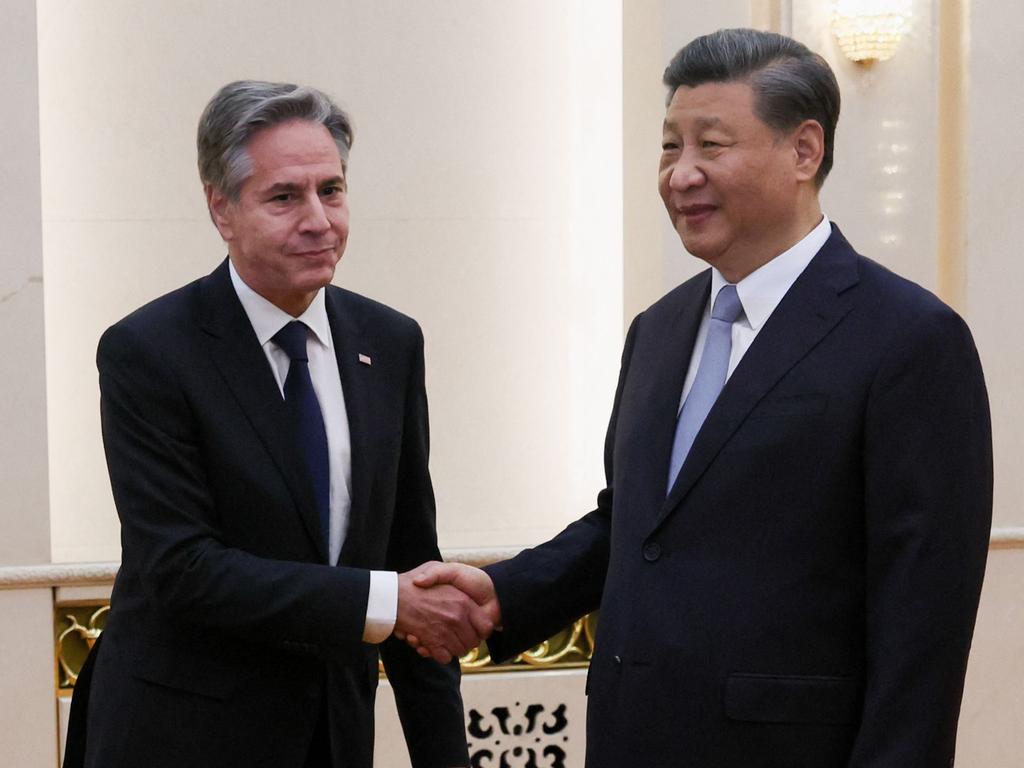

The risk for the likes of Xi and Putin is not so much that these politically ambitious entrepreneurs stand for office as that they bankroll rivals. And, riskier still, that they become capable of offering ordinary citizens a credible alternative route towards a modern and more just society. Both Putin and Xi rose to power on the back of steep growth and enriched their ruling castes; but they also blocked criticism. Only true believers still give credence to the current models of relentless success. Xi’s China is grappling with 21.3 per cent youth unemployment (fewer jobs from the tech sector), plunging property sales, indebted regional and local government, exports down by 16 per cent, and struggling households. Putin’s Russia, required to make sacrifices for a war that offers no obvious advantage for its disgruntled populace, struggles to enthuse the young. The rouble is plunging.

In both countries the embattled middle class yearns for more managerial competence and open discussion about policy options. Given the choice, politically engaged Russians and Chinese would probably prefer technocratic government to unchecked personality cults – providing the emerging leaders were fair and honest and capable of generating prosperity. That outcome is only feasible if businessmen are allowed to participate in the political game and are ready to contribute to policymaking in a meaningful, socially sensitive way. Instead they fear for their fortunes, affecting apolitical positions while waiting for succession struggles (more imminent, I assume, in Moscow than Beijing) to play out. They may consider this the prudent option. Few, after all, want to end up in Jimmy Lai’s cell or relive the prison years of Mikhail Khodorkovsky. But they run the risk of going down with the ship. It’s time for them to call out the strongmen.

The Times

The world’s richest political prisoner, the media magnate Jimmy Lai, has just won a minor victory in the Hong Kong courts but it is too soon to celebrate. It looks as though he will stay cooped up in jail for years to come. A snatched photograph showed him the other day in shorts and sandals being led into the exercise yard of the British-built Stanley prison for his daily 50-minute dose of fresh air. At 75, he is the oldest of the hundreds of politicals who were jailed by the Chinese regime after it crushed Hong Kong’s 2019 uprising. He is diabetic and has high blood pressure; the intense heat is taking its toll.