CCP rules: Hong Kong’s slide to proxy arm of Beijing’s law

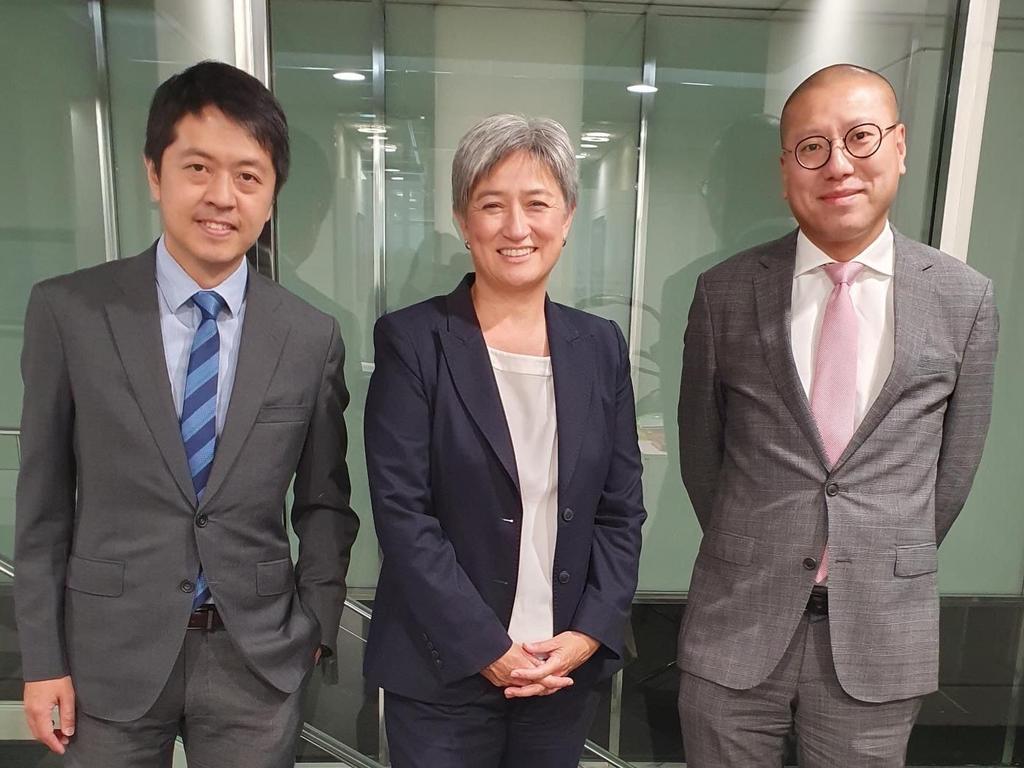

Bounties on eight dissidents who fled the territory steps up the pressure, even as Australia’s relationship with China stabilises.

Kevin Yam is a most unlikely outlaw. He is a charming 46-year-old cricket-playing Australian, a former commercial lawyer living with his young family in Melbourne, where he grew up and was educated. But this week the Hong Kong police, convulsed by Chinese leader Xi Jinping’s determination to bring not only the city but also the wider world to heel, announced a $HK1m ($191,800) bounty on Yam and Ted Hui, a former politician who now lives in Adelaide.

Yam returned to Australia last year after working for 17 years in Hong Kong, the city from which his parents came and which remains dear to his heart.

Since then he has voiced criticisms, especially of the catch-all national security law that he now has been accused of breaking.

Chief Superintendent Steven Li says his force – once respected for its fairness and independence from political direction but now struggling to gain local recruits – “won’t stop chasing”, even in foreign, sovereign jurisdictions, Yam, Hui and six others also accused of breaking the repressive national security law imposed on Hong Kong by Xi.

They are charged with what Richard McGregor, senior East Asia fellow at the Lowy Institute, describes as “thought crimes” – critical views and remarks about the way Hong Kong is being run under former police chief John Lee, who was chosen as chief executive by Beijing. In April, Lee hailed Hong Kong’s wide-ranging efforts towards China’s National Security Education Day, insisting such education “should start from an early age”, with all residents engaging “vehemently”.

The national security law, dramatically drafted and approved with just 15 minutes’ discussion by China’s National People’s Congress Standing Committee three years ago, claims a reach beyond the country’s borders. Canberra has suspended Australia’s extradition treaty with Hong Kong and eventually declined to complete one with China itself.

A 23-year-old student, Yuen Ching-ting, recently was charged under the law for posting online support for Hong Kong independence while she was studying in Japan. She was arrested while on a brief return visit to Hong Kong – where, as police assiduously hunted claimed thought-crime perpetrators, the overall crime rate soared 48 per cent in the first quarter of this year against the corresponding period last year, and violent crimes were up 22 per cent.

The Hong Kong authorities are seeking a High Court injunction to require all global online companies such as Spotify, Google and Meta to remove the 2019 protest song Glory to Hong Kong from their platforms internationally.

Hong Kong, which boomed economically in the 1950s and ’60s thanks to the energy and intelligence of the refugees who fled there as a haven from the tyranny of Mao Zedong’s China, has now become a dangerous place to visit by anyone who has expressed criticism of the ruling Chinese Communist Party or support for Hong Kong’s self-determination.

Anyone who has evinced such views, verbally, online or on any other platform, in any jurisdiction in the world, joins the eight named bounty targets as potentially a Hong Kong outlaw.

At the handover of Hong Kong from Britain to China in 1997, Beijing guaranteed to preserve for 50 years the city’s core systemic differences from the People’s Republic.

Yet halfway into that term, Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade is warning travellers there to “exercise a high degree of caution” since the national security law “could be interpreted broadly and you could break the law without intending to”. And if Australians living there are “concerned about the law, reconsider your need to remain in Hong Kong”, DFAT advises.

Article 38 of the national security law says it applies to “offences committed against the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region from outside the region by a person who is not a permanent resident of the region”. The law created four new criminal offences: secession, subversion, terrorism and colluding with foreign forces, including “inducing hatred towards the PRC or Hong Kong governments”.

It established a new National Security Council whose decisions are not subject to judicial review. It granted the police sweeping powers of surveillance, including of online communications, without judicial oversight. Sentences range from life imprisonment to a minimum of three years.

Yam explains to The Weekend Australian how he steadily was drawn into an institutional tussle within Hong Kong’s Law Society between “pro-democracy” and “pro-Beijing” lawyers – won convincingly, until the national security law was introduced, by the former – while “always being mindful of keeping my own law firm out of such debates”.

Meanwhile, he had been promoted to an equity partner and maintained mainland Chinese firms as clients until he left Hong Kong. He came back to Melbourne for family reasons, not wishing to join the ranks of “fly in, fly out” parents still working in Hong Kong while their families had shifted to Australia. By then, the only formal representatives of the legal profession remaining in public positions were all “pro-Beijing”.

Yam had opted to keep quiet publicly after the imposition of the national security law, although he maintained a monthly column on legal issues for popular newspaper Ming Pao.

He says a special security police section established under the national security law had been allocated a massive budget, “so friends and I anticipated that, having built up a huge apparatus, they were not going to announce that they had already arrested everyone who had committed an offence”.

Yam says “pure economics would ensure that they would keep going down their list, that they would keep finding new targets, and that even though I was a nobody, they might eventually come for me”. Which, this week, they did.

After leaving Hong Kong, Yam was appointed as a senior fellow at Georgetown University’s Centre for Asian Law and in May was approached to give evidence to the US Congressional-Executive Commission on China. He explains why he chose to accept: “While I might not be the most qualified lawyer to testify before the commission, I am the most available” now living outside Hong Kong.

He told the commission “Hong Kong judges saw the definition of their judicial oath being changed on them in 2021. They are now deemed” – by swearing allegiance to Hong Kong – “to have subscribed to a whole set of political, security axioms, such as upholding ‘the national sovereignty, unity, territorial integrity and national security of the PRC’.” Judges are required to fulfil their pledge “in words and deeds”.

Thus “the judges still serving in Hong Kong all know which way the winds are blowing. It means that for all the long political show trials with their ostentatious displays of common law court procedure, they will, whether consciously or subconsciously, almost inevitably side with the prosecution.” This adds up to “death by a thousand cuts from Beijing to Hong Kong’s rule of law and judicial independence”.

Within the legal profession, Yam says this week, the top performers “don’t want to become judges any more, not wishing to be tainted by association with the NSL”. It is inevitable, he says, that international companies steadily will reduce their exposure to deals signed or contracts agreed in Hong Kong.

“It may seem OK now, but what if in a few years the contract needs to be litigated and the settings have changed, and it then seems disadvantageous to litigate in Hong Kong? Who would be blamed? It’s natural that risk-averse in-house lawyers will start to suggest using other jurisdictions – Singapore, say, or the UK.”

Bankers and others, he says, will begin to consider whether it is better to base themselves in mainland China if China deals are the main reason to be in Hong Kong. “Over time, will you be able to rely on research on Hong Kong equities to provide fair evaluations?” he asks. “Once you take away freedoms, all you have left is a very expensive city to do business in.”

Yam says that leaving an AFL game last weekend – he is a devout Hawthorn supporter – “it was almost surreal, to walk past Melbourne police, not feeling conspicuous or scared as I would in Hong Kong”. But his return to Australia has not been without cost to this former high-flying commercial lawyer: “The big end of town here won’t touch people like me because of what we say about China.”

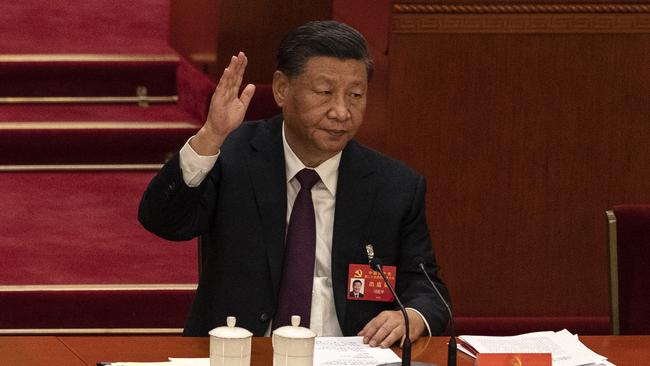

Meanwhile, Xi has transformed Hong Kong from a perceived embarrassment – even a challenge, as protests persisted – to CCP rule, to a key plank in his vaunted “rejuvenation” of China. He has said of his most recent visit to the city that he is “deeply glad to see that Hong Kong has restored order and is set to thrive again”.

The “two systems” part of the formula through which Britain handed Hong Kong back to the PRC – clearly differentiating it from mainland China – included the independence of its legal system, the freedom of its media, the accountability through partial elections of its government, its separate currency and migration controls, and preserving Cantonese and English as its main languages.

But now Hong Kong appears to be sliding swiftly towards China’s party-state culture, defaulting to “one country, one system” – in concert with a continuing strengthening, personalising and centralising of CCP rule in mainland China and an intensification of its global ambitions, even as Canberra’s relationship with Beijing stabilises.

Direct control of Hong Kong and Macau recently has been transferred from the Chinese government’s State Council to the Central Committee of the CCP, intensifying the oversight by the party, which in theory has no presence on the ground in the city, and thus elevating Hong Kong’s political significance at the heart of Beijing.

Jerome Cohen, emeritus professor at New York University’s school of law and a leading international expert on the Chinese legal system, has written that “comprehensive changes in Hong Kong’s criminal justice system have transformed it into an instrument of fear that has understandably intimidated a formerly vibrant society into political silence. An intensive surveillance system now reaches every aspect of society. Aggressive criminal investigation techniques now invade formerly protected freedoms of expression.”

Twenty years ago the city rated 18th in press freedom rankings, five years ago 70th and this year 140th of 180 countries. Media organisations critical of the authorities, such as Apple Daily, Stand News and Citizens’ Radio, have been forced to close following police raids, asset freezes and journalist arrests.

Xi boasts of thus achieving comprehensive control over Hong Kong, turning it from “chaos to governance”. He told his party congress in October last year the national security law “ensured that Hong Kong is governed by patriots”, adding: “We will crack down hard on anti-China elements who attempt to create chaos” there.

The long stand-off between young Hong Kongers, especially, and Beijing was triggered by a lengthy white paper published by China’s State Council in 2014, 18 months after Xi ascended to the leadership.

This clearly reflected Xi’s instinctive unease with the “one country, two systems” deal struck for the city’s future by Deng Xiaoping with Margaret Thatcher. While Xi has continued to pay lip-service to that phrase, in practice he has stressed instead that Hong Kong, like the rest of China, resides now in his New Era, not in Deng’s Old Era.

The white paper firmly repudiated hopes that Hong Kongers might have been freed, as implied in the Basic Law, to elect their own leaders from 2017, explaining instead that all might vote, but only for candidates acceptable to Beijing, and insisting that judges must recast themselves as “administrators” and must be “patriotic”.

Some Hong Kongers, the white paper said, were “confused or lopsided in their understanding” of one country, two systems. “The high degree of autonomy of Hong Kong is not full autonomy, nor a decentralised power. It is the power to run local affairs as authorised by the central leadership.” Beijing held “comprehensive jurisdiction” over Hong Kong, it stressed.

It was in response to the unyielding command-structure nature of that white paper that students and others intensified their protests in Hong Kong, including through the “umbrella movement” in a process that appeared, as it rolled on for five years, to pose a sometimes violent if inchoate challenge to Beijing. But the city’s authorities, echoing CCP rhetoric, frequently assert that young Hong Kongers lack agency, and champion free, democratic and rule-of-law values only because they have been suborned cunningly by malign – usually implying American – influences.

This is reflected in the national security law charges, often claiming the presence of sinister foreign “black hands”.

Deputy police commissioner Edwina Lau lamented recently as she prepared to retire that many Hong Kong “traitors” continued to collude with “foreign forces” in attacking the People’s Republic, including by having a protest song played at international rugby union and ice hockey tournaments instead of the PRC’s anthem, The March of the Volunteers.

On average someone is arrested every 4.2 days under the national security law, with 80 per cent of those charged denied bail. All the NSL-accused have been convicted, and most of a group of 47 democracy supporters, including former legislators, have been held in jail for more than two years awaiting trial.

Young Hong Kongers jailed for protesting are subject to a re-education program echoing that imposed on Muslim Uighurs in Xinjiang, with their prison days starting with goosestepping parades like those of the People’s Liberation Army.

The 47 are charged with “conspiracy to commit subversion” by organising primaries to help select candidates most likely to win seats at a legislature election in 2020, thereby participating in what prosecutors have called a “vicious plot” to wreak “mutual destruction” by controlling the legislature.

Chow Hang-tung, a 38-year-old barrister, is in jail for “inciting subversion” by organising a candlelight vigil commemorating the 1989 Tiananmen Square crackdown. Principal Magistrate Peter Law told her during a hearing that she was forbidden from using the word “massacre” or even “killing”.

Scores of trade unions, non-government organisations, student unions and political groups – most recently the Civic Party – have chosen or been forced to close since the national security law was introduced. After pro-democracy parties won control of 17 of 18 local councils in the 2019 elections, the government is slashing the directly elected council seats from 95 per cent to 19 per cent.

Public libraries have removed books deemed dangerously critical of China’s or Hong Kong’s rulers or authorities. Last year five speech therapists were jailed for 19 months each for publishing a series of children’s books about sheep resisting wolves that prosecutors claimed were allegories that were contemptuous of local and Beijing rulers. An episode of The Simpsons was banned on the Disney+ streaming service in Hong Kong because of a reference to forced labour camps in China.

Johannes Chan, former head of Hong Kong University’s law department, now a visiting professor at University College London, recently wrote: “In a city once known for its vibrant and diverse public square, no one feels comfortable sharing critical or even lightly satirical remarks or cartoons about the government in public, or sometimes even among friends in private.”

Partly as a result, Hong Kong’s publicly funded universities now employ more academics from mainland China – about 35 per cent of the total – than from the city itself, as Hong Kong academics have joined the exodus of talent, with more than a quarter of a million leaving since the national security law was introduced.

The authorities are throwing the book at, especially, Jimmy Lai, the highly articulate 75-year-old China-born British businessman, founder of clothes chain Giordano and of a popular media group led by Apple Daily, who has been in jail for 2½ years. When Hong Kong’s legal system, in a succession of judicial reviews, agreed to him being represented by a British lawyer, chief executive Lee successfully sought intervention from Beijing so that Lai instead will be required to be represented by a local, security-system-approved lawyer.

Lai is accused under the national security law of “foreign collusion”, reported to include a meeting with a previous US secretary of state, a digital platform talk show in which he interviewed foreign politicians, and publication of an English-language version of Apple Daily.

“Freedom of speech is a dangerous job,” Lai wrote from prison. To which, Yam says: “Amen.”

Rowan Callick is an industry fellow at Griffith University’s Asia Institute.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout