The ‘living library’ of diseases could prevent the next Covid

Porton Down, the government’s top-secret science and technology campus, is home to what may be the world’s deadliest freezer.

Hidden in a quiet corner of the Wiltshire countryside is perhaps the word’s deadliest freezer. Inside a high-security green warehouse, there are 22 giant metal vats kept at -190°C and filled with samples of every kind of nasty disease you can think of: yellow fever, herpes, flu, gonorrhoea, zika and mpox.

It is part of Britain’s culture collections, run by the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA), which store more than 10,000 strains of bacteria, viruses and fungi and have been in operation for more than 100 years. This “living library” of different microbes is based at Porton Down, the government’s top-secret science and technology campus.

Five years on from the Covid pandemic, the “scientific treasure trove” of samples - some of which date back to the First World War - are being used to help ensure that the UK is better prepared for the next time there is a deadly outbreak.

The 70 staff working here collect and grow different types of bacteria, viruses and cells in the lab. These are then shipped off to scientists around the world and used to benefit “all corners of public health” and medical research, including developing drugs, diagnostic tests and new vaccines.

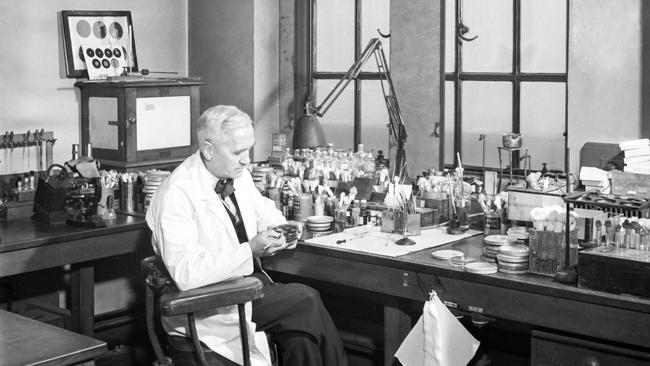

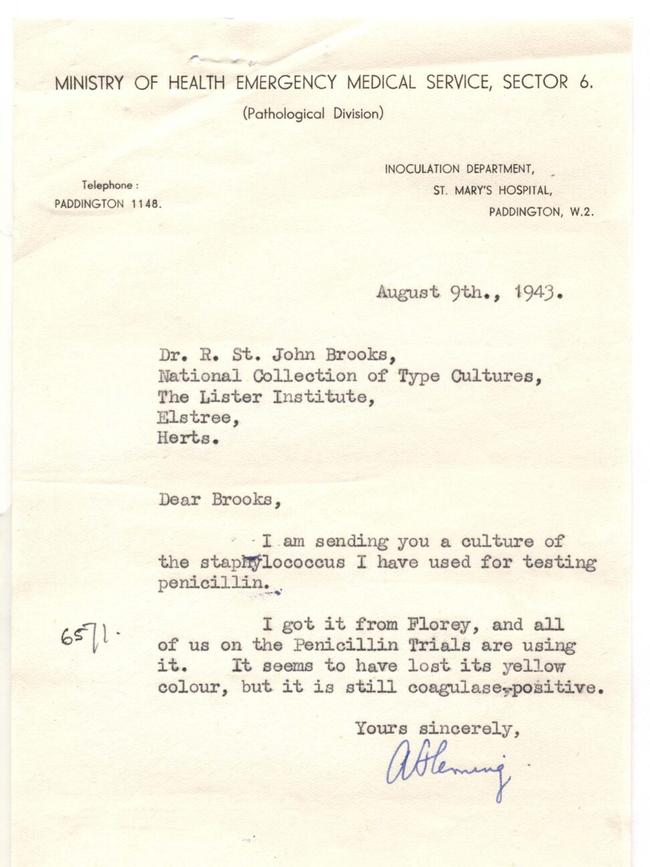

Hannah McGregor, the head of culture collections at UKHSA, showed The Times around Porton Down on a visit to mark British Science Week. Scientists began the national collection in 1920, and McGregor explained that she is “most fond of the historic bacteria”. She pulled out one vial containing a strain of bacteria which was deposited in 1943 by Sir Alexander Fleming - whose discovery of penicillin revolutionised medicine.

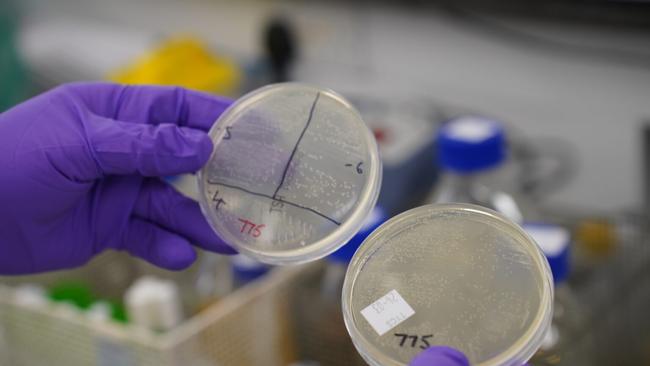

The microbe, known as Oxford Staphylococcus, had been used in the penicillin trials at Oxford University. It continues to play a crucial role in medical research, and monitoring antibiotic resistance - one of the world’s biggest global health threats.

“We can compare wartime bacteria with modern versions. They often look very different, even if it is the same species. It helps us to see how bacteria has mutated and evolved over time,” McGregor said. Scientists are able to test antibiotics on different strains of bacteria to see if they still work, or if bacteria have developed resistance.

As well as 5,500 types of bacteria, there are 300 virus strains kept in freezers on the site, in the National Collection of Pathogenic Viruses. Medical researchers around the world “shop” for whatever virus they need to help create treatment or vaccines.

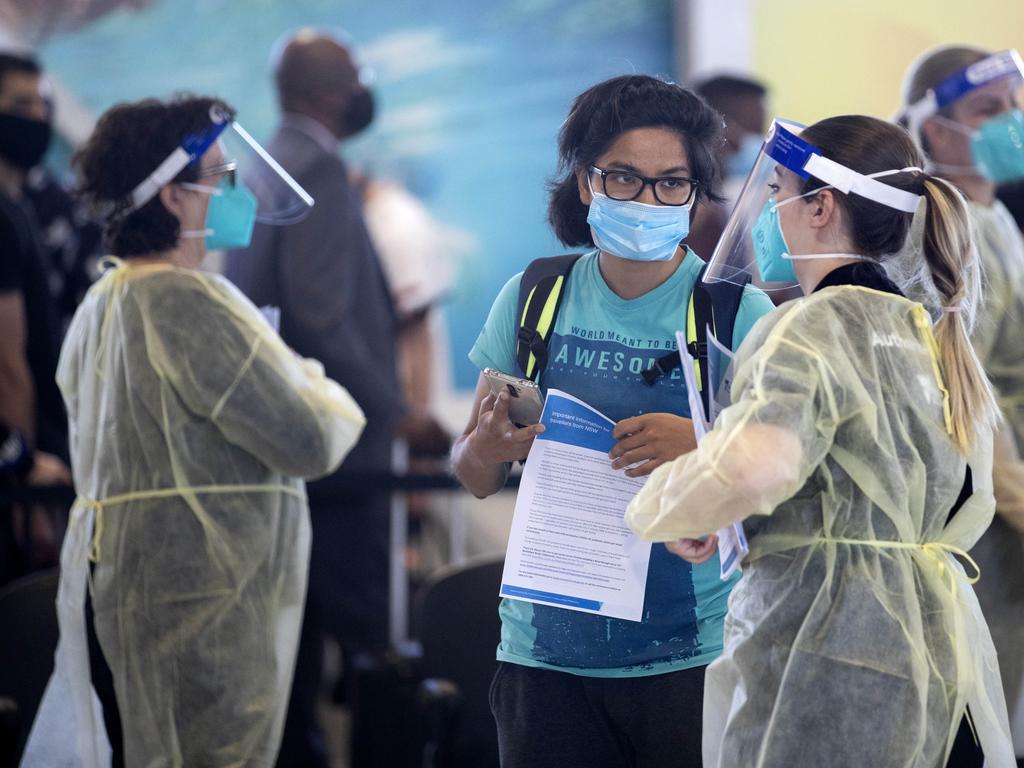

During the Covid pandemic, the collection played a pivotal role in vaccine development - with strains of coronaviruses, including Sars, Mers and the common cold, provided to research teams around the world.

“We’ve got a library of viruses going back 25 years,” said Jane Burton, who leads the virus team. “It is really about ensuring we are prepared. If a weird and wonderful virus does start to cause a problem, there is a reasonable chance that we already have it in the collection.”

The collection is not-for-profit and does not receive funding from the British taxpayer, but covers costs by selling its samples to laboratories around the world, with about 2,000 shipments each year.

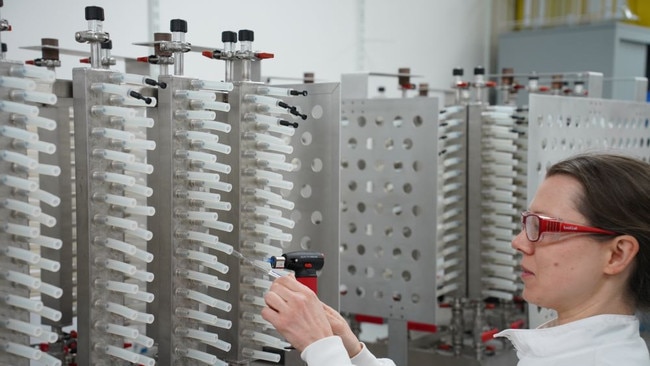

As well as storing viruses, bacteria and fungi, the site at Porton Down is used to grow collections of different types of human cells. These are shipped around the world for use in medical research by scientists and pharmaceutical companies, unlocking new treatments for conditions including Alzheimer’s disease and cancer.

Jim Cooper, who leads the cell culture team, described the “highly specialised process” used to grow the human cells in flasks in an incubator. “We’re trying to recreate the biology of the human body in a test tube,” he said. “We keep the cells at body temperature of 37C”.

Cooper gets out some brain cells - or neurons - from the incubator and looks at the spindly and spiky structures through the microscope. “These brain cells can be used by researchers to look at drug discovery for things like Alzheimer’s disease,” he said.

Cooper, who has worked at the site since the 1990s, said: “We have grown cells from every part of the human body - muscles, skin, kidney, liver, brain.”

He described cell cultures as being like a “Swiss Army Knife” because they have so many diverse uses. During the pandemic, the cell collections at Porton Down were used to grow samples of the Covid-19 virus - as viruses only replicate inside human cells - so that the vaccine and tests could be developed. “When virologists discover a viral strain or potential pandemic strain, they need to be able to cultivate that virus and isolate it and grow it,” he said.

“It’s not over exaggerating to say that if this collection didn’t exist, we wouldn’t have been able to find the answers to Covid.”

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout