‘The babies screamed and cried; proof someone had caused them extreme pain’

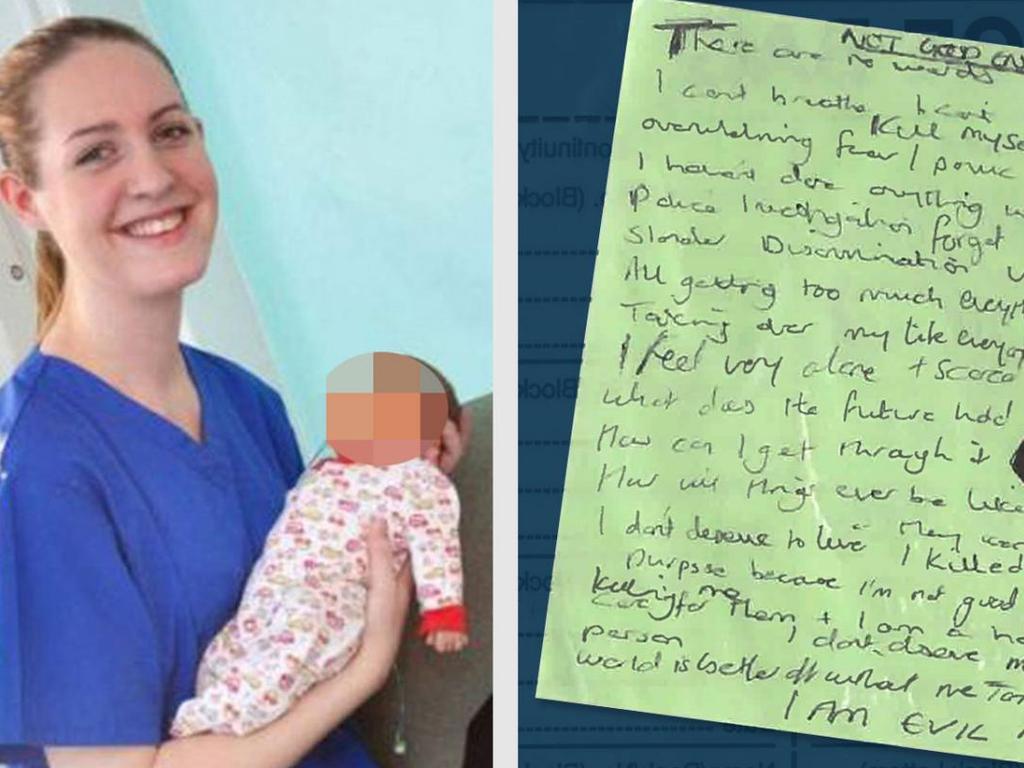

‘At first there was a feeling of disbelief’: the doctor who carried out the detective work on Lucy Letby’s murder method reveals how she uncovered the truth.

The moment Dr Sandie Bohin worked out how Lucy Letby was murdering babies using lethal injections of air will stay with her for ever. It was late 2019, and police had asked her if she could explain why babies were collapsing and dying at the Countess of Chester Hospital.

Bohin, a neonatologist and consultant paediatrician who was one of the prosecution’s star witnesses during Letby’s ten-month trial, said: “I was sitting at my dining room table in the winter, and it was dark outside, and I was looking at this baby’s X-ray, thinking, ‘This baby has had an air embolism’.

“Then I thought: ‘It can’t be.’ I’d never seen anything like that in my career … but nothing else explained it.

“The X-rays were in front of me, several of them, all showing air in the babies’ vessels. That’s when I thought: ‘No, it has to be, and it has to be deliberate.’ ”

In her first interview, Bohin, who lives in Guernsey, described the process of gathering the evidence used to convict Letby, proving the nurse killed babies by injecting air into their bloodstream or stomach, causing lethal bubbles.

“What you don’t normally see are large columns of air in the blood vessels,” she said. “So having seen that you think: ‘How did it get there?’

“At first there was a feeling of disbelief, really. You just can’t match up what you are seeing on X-ray and in the clinical notes with what you know normally happens on a neonatal unit.”

Bohin and Dr Dewi Evans, another consultant paediatrician, provided the expert medical opinion that this month helped convict Letby, 33, of seven murders and six attempted murders.

Bohin discovered there is little medical research into air embolus - foreign material, such as air, that obstructs a blood vessel - in humans. A 1989 study on rare air embolisms in newborn babies by the Lawson Research Institute, St Joseph’s Health Centre, in London, Ontario, and the department of paediatrics at the University of Western Ontario helped explain the strange mottling rashes observed on the skin of Letby’s victims.

There is more research on air embolus from animal studies, something Letby’s defence team brought up during the trial.

“The defence kept making reference to us being reliant on animal papers,” said Bohin. “At one point Ben Myers KC [Letby’s barrister] said I was using a whole ‘menagerie’ of animal papers. I had to make clear: it’s unethical to inject babies with air and see what happens. We have to rely on animal models a lot of the time in medical research.”

Extreme pain

During Bohin’s research, one detail that stuck out was that some of the babies “screamed” after being attacked by Letby. “Babies will cry if they are in pain, obviously, such as when you take blood or put in a drip,” she said. “That hurts, and there’s no getting away from it. But to have a premature baby screaming is really unusual. What was described on the ward was babies screaming for up to 30 minutes. Now that is just unheard of. Somebody had done something to cause those babies extreme pain.

“With an air embolus, the air can get locked into the heart and it can also go into one of the arteries which supplies oxygen to the heart muscle, and the baby effectively has a heart attack. That is extremely painful.

“I remember the mother of one of the babies said she could hear in the corridor her child making a noise that a baby should never be making. That will be for ever etched on her memory.”

Clues in paperwork

The attempted murders of Baby F and Baby L, two children poisoned with insulin, would be pivotal in proving sabotage at the hospital. Letby’s defence did not contest the fact the babies were poisoned, but rather argued somebody else had done the poisoning - a theory rejected by the jury.

The dose for Baby L was shown to be double that of Baby F, suggesting an intention to kill. Blood tests showing high levels of insulin in the blood were missed by doctors, the abnormal test results buried under mounds of hospital paperwork. It was only when Evans came to review the cases for the police years later that the abnormal test results were uncovered, buried in a stack of medical notes. One of the baby’s medical files alone contained 5,000 pages, Bohin said.

Letby also managed to slip through the gaps in the coronial system, despite six babies out of the seven she murdered having a full post-mortem examination. In each of the six cases, their deaths were ascribed to natural causes by pathologists at Alder Hey hospital, providing an incorrect cause of death for the death certificate. We have learnt that hospital managers in fact asked the Cheshire coroner, Dr Nicholas Rheinberg, to investigate the seven baby deaths in February 2017.

The coroner declined, according to sources, telling the trust he was not a “quality-assurance service” for the NHS. Rheinberg retired that year.

Staff shortages

New evidence shows how Letby thrived in the chaotic, short-staffed neonatal unit. In December 2015, Alison Timmis, a paediatrician, emailed hospital bosses, saying that the ward and its babies were not safe.

“At several points we ran out of vital equipment such as incubators,” she wrote in a two-page email to the chief executive, Tony Chambers, copying in Ian Harvey, the medical director.

One baby had to be intubated - which means inserting a breathing tube - in the middle of the room because they had run out of bed space, she claimed. “Over the past few weeks I have seen several medical and nursing colleagues in tears … they get upset as they know that the care they are providing falls below their high standards,” she wrote. Letby used staff shortages to work extra shifts. Being left alone with children at night gave her the time and space to attack and kill.

Last week a Sunday Times investigation revealed managers had repeatedly failed to act on doctors’ concerns after babies started to collapse and die in 2015 and 2016.

Chambers resigned in 2018 after agreeing a non-disclosure agreement with the trust. He then took jobs at several NHS trusts, which has prompted calls for tougher regulation of managers.

He said he recalled Timmis’s email, saying: “I remember visiting the unit on a number of occasions to talk with staff and listen to their concerns. The outcomes of such visits were shared with the senior nursing team. There was an ongoing drive to increase the staffing skill mix on the unit.” He added: “I will give evidence at the independent inquiry. It is the right place to explore these complex issues.”

further investigation

New documents show executives at the trust met in February 2017 and discussed the need for “strong messaging” ahead of “another Morecambe Bay” - a reference to a maternity scandal in Cumbria when 11 babies and a mother died due to failures in the standards of care.

Weeks after the meeting, instead of contacting police, the trust asked a criminal barrister to meet the doctors and decide whether a criminal offence had been committed.

Cheshire police are now in “phase 2” of Operation Hummingbird and have been given pounds 7.4 million to investigate other potential offences committed by Letby. Police sources say at least 12 suspicious baby collapses have been identified.

Further suspected offences took place at Liverpool Women’s Hospital, where Letby conducted advanced training as a neonatal nurse.

Whitehall sources say Steve Barclay, the health secretary, believes the decision on whether to upgrade a public inquiry into Letby’s crimes to statutory level should rest with the families of her victims.

“If the families believe that is the right option, no one is going to stand in their way,” a Whitehall official said.

Richard Scorer, head of abuse law at Slater and Gordon, who is representing two of the families from the criminal trial, said: “There is a deep concern from the families that there may have been a desire from the hospital management to protect the reputation of the hospital at the expense of patient safety. The families want an inquiry to have the powers to compel witnesses, meaning a statutory inquiry.”

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout