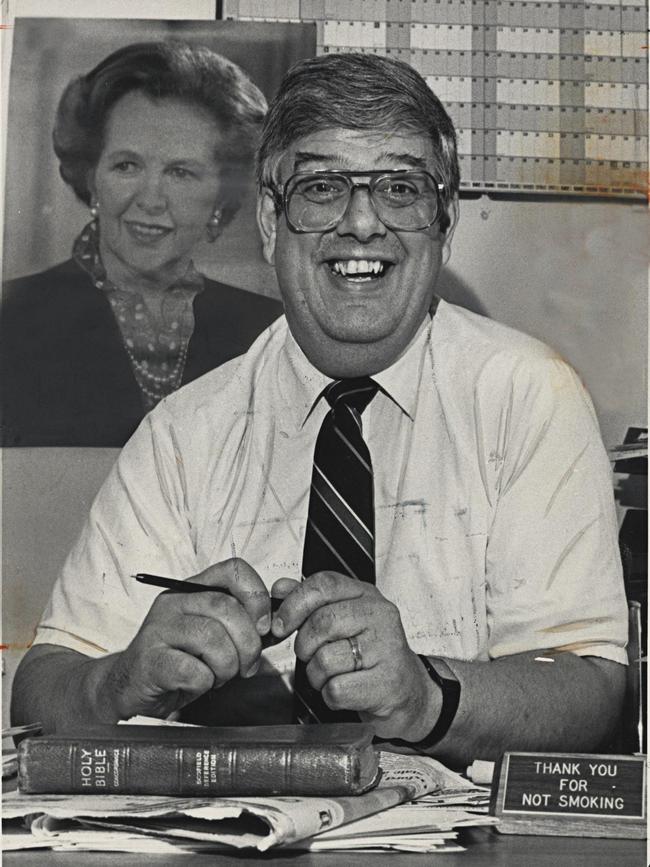

Thatcher’s spin doctor Harvey Thomas transformed conservative campaigns

From burnishing Thatcher’s image to inventive stage tricks, arguably no one has done more to improve conservatives’ electoral prospects than Britain’s first ‘spin doctor’.

OBITUARY

Harvey Thomas, CBE, communications expert, was born on April 10, 1939. He died of a lung complication on March 13, 2022, aged 82

On the evening of October 11, 1984, Harvey Thomas, Margaret Thatcher’s communications chief and reputedly Britain’s first proper “spin doctor”, had been helping the prime minister rehearse the speech she was due to deliver to the Conservative Party conference the following day. Shortly before midnight he left her room in Brighton’s Grand Hotel and returned to his own. At 2.54am, as he slept, a huge IRA bomb exploded in the room below.

Thomas was a big man — 6ft 5in tall and 18 stone with huge hands and size 17 shoes. Yet he was blown upwards one entire floor before crashing down three floors and coming to rest on a steel girder with tons of debris on top of him. He lay trapped, with water from burst pipes gushing past him in the darkness. He was certain he was going to die, but as a born-again Christian he was more concerned that his wife was due to give birth to their first child any day and would be left alone.

Thomas did not die, though five others did. Within two hours he was rescued by firemen and taken to hospital. Miraculously he had escaped serious injury. Irrepressible and relentlessly upbeat by nature, he appeared before the press, still covered in dust. He then discharged himself and returned to ensure that, later that morning, the conference he had helped to organise resumed and that Thatcher delivered her speech in defiance of the terrorists. “In those days we hadn’t been clever enough to invent post-traumatic stress, so we just got on with it,” he said.

Thomas later received a bill from the hotel and wrote back: “Would you mind giving me half a night’s discount because the room didn’t exist after 3am?” He also recovered his dust-covered Bible, which was the only possession of his to survive the blast, and kept it in a plastic folder for the rest of his life.

There was another curious postscript to the bombing. Years later Thomas decided he had a Christian duty to forgive the bomber, Patrick Magee, who was serving eight concurrent life sentences in Northern Ireland’s Maze prison. He wrote to Magee; Magee replied. In 2000, after Magee had been released under the terms of the Good Friday agreement, the two men met for several hours at a mutual acquaintance’s home in Dublin. Over time they became friends, and Thomas later recalled how Magee once visited his London home when his family were all there. At one point Thomas’s youngest daughter, Lani, looked at Magee and said: “’Pat, you do realise that if you’d succeeded in killing Daddy I would not be here?’ He was in tears.”

Thomas accepted that Magee genuinely believed republicans had no option but war. He even agreed that republican violence, though morally wrong, ultimately achieved its end. “Nationalists have been terribly badly treated by the British for 200 years,” he told an interviewer. “Historically, if there had not been a violent uprising in Northern Ireland we would probably still be treating the Irish and behaving terribly towards them.”

That was a rare instance of Thomas disagreeing with Thatcher, a woman whom he faithfully served for a dozen years and whose public persona he did so much to burnish.

Harvey Thomas was born in north London in 1939 and swiftly evacuated to Devon until the war ended. His father, Kenneth, was a barrister and his mother, Olga, a teacher. Aged 11, he was “born again” while attending a youth camp on the Isle of Wight run by the Crusaders, a Christian organisation.

He was educated at Westminster School but was not academic, leaving with five O-levels and no A-levels. He tried law, without enthusiasm, then auditioned for Rada and was accepted, but by then he had gone to work for the American evangelist Billy Graham, helping to stage a rally at Manchester City’s Maine Road stadium. That led to him enlisting at the Northwestern Bible College in Minnesota, which he financed by working night shifts for the US mail service, and further studies at the universities of Minnesota and Hawaii. While in Honolulu he also worked as a disc jockey on a local radio station and had to announce President Kennedy’s assassination in 1963.

Thomas adored Graham. He worked for him from 1960 to 1975, organising his world tours and giant rallies, including one that attracted more than 100,000 followers to Wembley stadium in 1965. During those 15 years with one of the great public performers Thomas developed the presentational and communication skills that he would later deploy to effect on behalf of the relatively hidebound Conservative Party.

He left Graham to become an international public affairs consultant. Two years later, as he liked to tell it, he had a layover in Senegal while flying back from South America. The Senegalese immigration officers looked at his passport and laughed, saying “Great Britain isn’t great any more.”

Back home James Callaghan, the prime minister, was battling militant trade unions and the Winter of Discontent loomed. Thatcher was leader of the opposition. Thomas had no previous political experience but decided he had to do something. He walked into Conservative Central Office, offered his services, and over the next decade he transformed the Tories’ communications strategy.

He helped to organise all of Thatcher’s three winning general election campaigns, introducing big star-studded rallies with comedians, lights, loud music, balloons, giant screens and lots of American-style razzmatazz.

When Norman Tebbit succeeded John Gummer as party chairman he was concerned that Thomas lacked the political expertise to oversee the party’s communications. Yet no one could question his ability to stage an event.

“Under Harvey Thomas’s supervision our rallies had by now moved into the twentieth century with a vengeance,” Thatcher noted wryly in her memoirs. “Dry ice shot out over the first six rows, enveloping the press in a dense fog; lasers flashed madly across the auditorium; our campaign tune, composed by Andrew Lloyd Webber for the occasion, blared out; a video of me on international visits was shown; and then on I walked to deliver my speech, feeling something of an anticlimax.”

He prepared the public appearances of a woman he called “mother”, helping to craft her image and make her appear more human, less wooden. Not only did he advise her on how to approach interviews, deliver speeches and modulate her voice, even on her dress, but also he invented a gas-powered lectern that automatically adjusted to her height. He introduced her to a novel device called the autocue ahead of her address to a joint session of the US Congress in 1985.

“In fact, I borrowed President Reagan’s own autocue and had it brought back to the British embassy where I was staying,” she recalled. “Harvey Thomas fixed it up and, ignoring any jet lag, I practised until 4am.”

Thomas took particular pride in the record 13-minute ovation that followed Thatcher’s closing speech at the 1989 party conference, though he explained self-deprecatingly, “The party’s ready to let off steam at the end of the week. I just opened the valve, and off they went.”

He also offered media training to initially sceptical Conservative ministers and MPs unused to the television era. “Talk in headlines. Caring words. Look the part,” he would tell them.

Thomas (who once remarked, “I love Mrs Thatcher, but not as much as I love the Lord") said he never felt any conflict between his Christian faith and the policies he was promoting, arguing that Toryism and evangelism shared the same core values of freedom, choice and individualism. He argued that razzmatazz was important to win voters’ attention, but useless if there was no authentic message to communicate.

Throughout he was helped by his German-born wife, Marlies, who acted as his personal assistant. They had first met at a conference in Switzerland, married in 1978 and had two daughters: Leah, who was born five days after the Brighton bomb and is now a musician, and Lani, who is deputy executive director of a Christian charity.

Thomas was appointed CBE in Thatcher’s resignation honours list. He stayed on for a year after John Major succeeded her as prime minister in 1990, then returned to his international PR consultancy. He advised the former South African president FW de Klerk when his National Party ran against Nelson Mandela’s African National Congress in their country’s first free election in 1994. Thomas also organised Commonwealth heads of government meetings and the Middle Eastern equivalent of the annual Davos economic forum in Jeddah. Before British ambassadors took up their postings overseas he gave them media training.

He was actively involved in Christian broadcasting ventures around the world and made regular appearances on the Today programme’s “Thought for the Day” slot on BBC Radio 4.

A member of the Cremation Society of Great Britain, he blocked the Kremlin’s demand in 1993 that Anna Pavlova’s ashes be returned to Moscow from the Golders Green Crematorium because there was no evidence that the great ballerina would have wanted that.

Thomas neither smoked nor drank. For relaxation he had his model train set which began when Lani, his daughter, gave him a single Flying Scotsman engine and one small loop of track more than two decades ago. He added models and scenery to it whenever he travelled abroad and ended up with 33 model engines, five big loops and 27 sidings. It had completely taken over the garage of his north London home.