The death of a pope, at a time when Rome has almost no temporal power, and when in most of the anglophone world Catholicism is very much a minority interest, remains a curiously public participation sport, in which everyone gets to award marks to the man just gone and sizes up the runners and riders for the contest ahead. Commentators on the BBC who might once have attended a church wedding suddenly hold forth on the legacy of the Second Vatican Council. The New York Times will run long features about a church again “in crisis”.

Celebrities who think the church is some impenetrable redoubt of medieval superstition run by sex-obsessed old men in frocks will hold forth on how it now must get with the programme, ordain women, smile on divorce, and stop saying disobliging things about gays. Public intellectuals who think the Immaculate Conception is something to do with the virgin birth will happily prattle away on who, from among a couple of dozen or so names of cardinals they had never heard of until 15 minutes ago, is now the right choice “to take the church into the modern world” .

Unable to comprehend any human activity in anything other than a familiar political taxonomy, they will tell us again that the coming contest is between “conservatives” and “liberals”. These are not only politically comprehensible terms. They also serve as handy moral descriptors: liberal=good; conservative=bad. (Confoundingly for the modern progressive mind, today it’s often the black and brown men who are bad in this telling, and the white ones who are good.) Labelling the papabile in this way means the interested viewer can sit down with a cut-out-and-keep guide to the conclave, cheering on the good guys while he waits for the white smoke to emerge from the Sistine Chapel. If all goes really well, and the princes of the church are fully up on the moral compass of modern novelists and Hollywood screenwriters, we’ll get a pontiff with female genitalia. So be it. Perhaps it’s a backhanded tribute to the enduring relevance of the faith they insist is obsolete that so many in our media take an outsized interest in its proceedings.

For the rest of us a papal interregnum provides an opportunity to reflect on the real lessons of the papacy just ended and to ponder - prayerfully - what they should mean for the cardinals preparing to inaugurate a new one.

The common misunderstanding about Francis is that he was a “liberal” to John Paul II’s and Benedict XVI’s “conservatives”. This explains the confusion many felt when Francis would puzzlingly refuse to condone abortion rights or married priests, or as tales of his martinet-like rule over the Vatican filtered out beyond St Peter’s Square.

A better way to understand the last 50 years of the papacy - and what may come next - is to grasp that all three of these men were proselytising the same Catholic truths, but in different ways and, crucially, with different emphases.

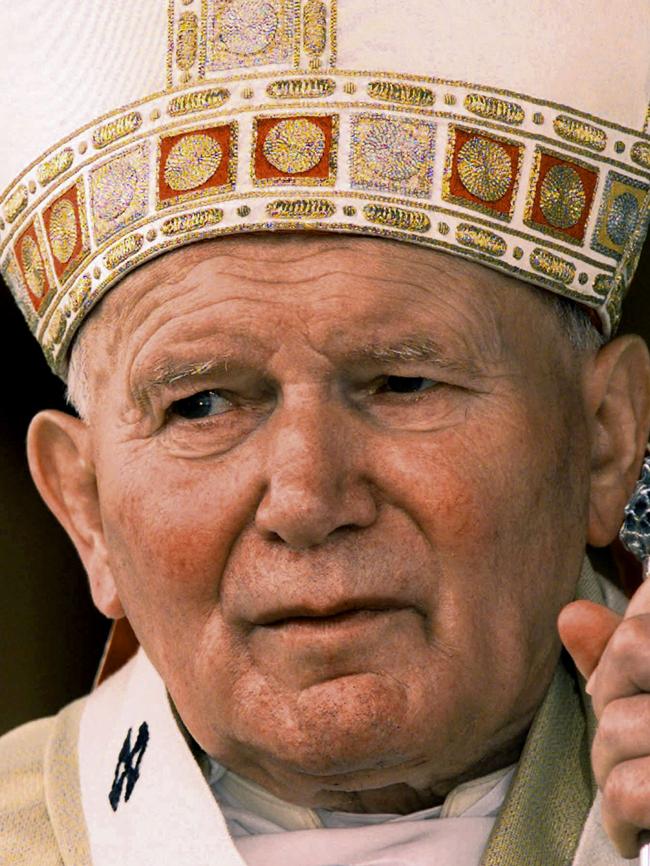

John Paul II was a charismatic force for human liberation, while at the same time a fierce intendant of the doctrine and moral teachings of the church, which in the confusion that followed in part from Vatican II had become somewhat soggy. Benedict was an intellectual, an eminent theologian, constantly striving for ways to marry the message of ancient scripture and medieval philosophy to the necessities of a Facebook world.

Francis represented the desire of cardinals in 2013, after 35 years of church leadership that re-emphasised the importance of the church’s moral authority over Catholics’ personal choices, to restore to centrality the social justice mission of the church. That’s why the late pope wasn’t every dogmatic Catholic’s cup of tea. This is especially true of the many recent converts from the looser doctrinal strands of modern Protestantism. These are usually the ones, especially over here in America, with a slightly terrifying insistence on rigid enforcement of the Catholic rules. Lifelong Catholics are more likely to regard Christ’s injunctions to alleviate human suffering and to extend compassion to the disadvantaged and the sinner as most central to their faith.

Of course each of these popes made errors. (They are not, after all, infallible.) The appalling failures to root out those responsible for sexual abuse and those responsible for covering for it are stains that will endure for many years.

But between them they promulgated the basic truths of the Christian faith. The next pope will surely attempt some synthesis of these variant truths. It might help also if he were vigorous and with a familiarity with the church in the Global South, where it has been growing most fruitfully and from whence the reverse evangelisation of the tired north is emerging. He may also be called upon to play a global pastoral role at a tense geopolitical moment. (The superstitious or spiritually minded will have noticed that there were new popes elected in 1914 and 1939.) He will also face a unique challenge in the 2,000-year history of the papacy: the reaffirmation of what it means to be human in an age when artificial intelligence will dominate life.

Francis, in his personal humility and compassion for the least advantaged, showed a face of the church sometimes hidden in the doctrinal and moral rigidities the universal, timeless church presents. With a planet in turmoil, and emerging signs of a revival in Christian observance, his successor will want to turn that face to an even wider world.

The Times

One of the many joys of being a Catholic in a post-Christian era is that, every ten or fifteen years or so, we get to listen as people who reject just about everything the church represents lecture us with great conviction on who should be its next leader.