Princes’ conservation row reveals a real rift

The organisation itself said, with unfortunately patronising language, that “in secure parts of the continent with low levels of education” there must be “professionalisation” to save wildlife. This, in practice, means employing large bodies of rangers, sometimes armed, paid and trained to a higher standard than members of their nation’s army.

Although they are members of local communities, rangers selected by the outsider-charity have a lot of power and authority. It can be exerted not only over poachers incentivised by a wicked international trade but over their fellow tribesmen and women. Resultant abuses - rape, brutality - were lately uncovered in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Ask the human rights charity Survival International and it will offer you plenty of other examples. Even without physical abuse, a wildlife charity’s “professionalisation” can mean grievous disrespect and impoverishment. When park-keeping regulations cut off people from grazing, herding or food-gathering areas that have been used for generations the accusation of “green colonialism” is not unfounded.

Living here in a patch of our own country bordered by protected landscapes and wildlife havens we often joke that most “conservation” is a form of landscape gardening, as deliberate as farming or building. An untouched primitive view is rare in Britain so bracken gets cut back to give heather a chance, streams are cleared, saplings guarded from squirrels; in bird reserves, traps kill foxes and crows. Sometimes respect for one species harms another and humans choose: the more badgers you protect, the fewer hedgehogs you’ll see.

This demands obedience from humans: dogs on leads, specific paths across wild heathland, fences around wild orchids, restricted grazing. Fair enough. As a democratic society in a smallish island nation we generally approve of this conservationist “gardening”.

But Africa is not our garden. It is not our “parcel of land” to be organised from outside by Europeans and Americans. Its inhabitants are not under our orders as farmers, hunters or gamekeepers simply because we are richer. Any interference needs agreement, and perhaps irresistible bribery via aid, but also demands fairness. The human rights and lifestyle choices of an American billionaire or a British prince are no greater than those of a barefoot African. And both, hard though it can be to admit, score higher than a rhino or an elephant.

So just because a charity has affluent donors, a budget of $155 million a year and a nobly born figurehead, it doesn’t entitle it to full gardening rights. The model of such charities, including traditionally the WWF, has been condemned by some as oppressive when animal habitat is turned into parks and game reserves and the locals turfed out. Luxury tourism - like Harry’s own joyful whizzing round a hippo lake on a jet ski as related in his book - should not outrank the people who lived in partnership with nature before.

Caroline Pearce, the executive director of Survival International, wrote here that it had been fully a decade since the charity first complained to the prince and the leadership of African Parks about violations of indigenous people’s rights. “Across Africa and Asia,” she wrote, “conservation is for many indigenous people the primary threat to their existence.”

The charity, whose budget is barely a tenth of African Parks’s, claims successes in resisting both wildlife and commercial interference on behalf of Maasai, Kalahari Bushmen, Yanomami in Brazil and Dongria Kondh in India. There are smaller, less obtrusive conservation wildlife charities that work close to the ground and are led by African women and men. The result can often be fairer but, let’s face it, probably less dramatic in the saving of fragile creatures and habitats.

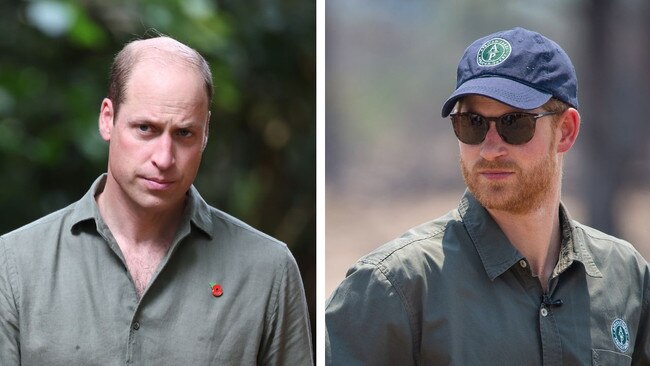

It’s a dilemma. You need a heart of stone not to be moved by Harry’s emotional descriptions of animals falling victim to savage poachers and, indeed, to understand how he needed Africa’s noble animals “to fill the hole in my heart left by soldiering”. He feels himself enlisted in “a war to save the planet”. But it is ironic that a man who accuses others of racism and stands alongside Black Lives Matter should have displayed relatively little concern about millions of Africans who are unlikely to get jobs as rangers or guides to rich visitors: women, children, aged gatherers of medicinal herbs.

His passion for wild creatures is admirable but so is his brother’s caution about methods. Maybe William’s long training for powerless Commonwealth kingship, and the recollections-may-vary caution brilliantly exercised by the late Queen, make him more likely to remember that people with unimaginably different lives and priorities have needs and feelings too.

In donating and backing conservation in far-off countries we need to pause and ask uncomfortable questions about our rights and theirs. Just as in other politics we should interrogate the equally dangerous idea that an armed invasion will spread liberal human rights and peaceful democracy, whether the recipients want it or not.

The Times

A reported gulf of opinion between two princes over African conservation is more than a tattling royal story; it usefully reminds us of a difficult balance and the way that good intentions can tip into cruelty. William, we are told, favours schemes led by local communities: collaborative and diplomatic, and therefore probably slower to produce dramatic results for endangered species. Harry, the president and now a director of African Parks, has been voluble in wanting faster and tougher action. He has made clear his view that when people are coexisting with animals there must be “fences to separate the two and keep the peace. Once a fence is up you are now managing a parcel of land. Different rules have to apply, whether we like it or not.”