The supermodel saving Kenya’s gentle giants

Trish Goff and David Bonnouvrier built a home next to Kenya’s Lewa Wildlife Conservancy and learned that trying to protect the country’s wildlife begins with helping people.

On a trip to northern Kenya, David Bonnouvrier and Trish Goff, who have been together since 2011, got lost in the bush at night after their Land Rover broke down. Goff was in shorts and Birkenstocks. They had given away their water and bananas to some kids they saw en route, thinking they’d be at their friend’s place in no time. Hours later, walking in the dark, they stumbled upon a small settlement of Samburu, one of the ethnic groups in the area. The Samburu elder walked them hours more to a meeting place where they could be picked up by a ranger. “We sent his village a goat, and him a goat, too, once we were back,” Goff recalls.

Lessons learned: “Always stock your car. And people are kind.”

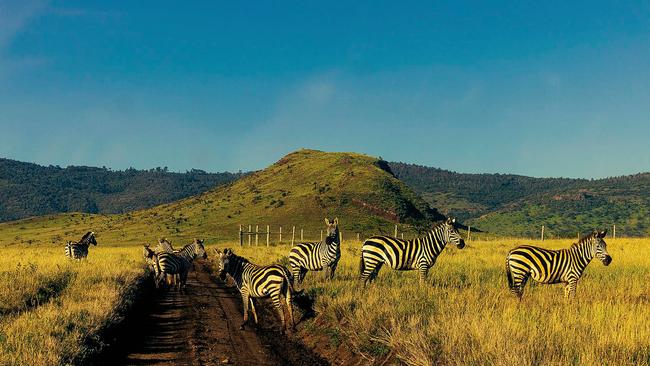

Bonnouvrier, the chief executive of DNA Model Management, and Goff, a model-turned–broker with Sotheby’s International Realty, knew nothing about Kenya when they first visited in 2014. They landed from New York, looking for a warm place to build a home together. Eventually they ended up adjacent to the Lewa Wildlife Conservancy, a 62,000-acre sanctuary founded in northern Kenya in 1995, which had a few private lots available near its borders. Today, on the 30-minute ride from Lewa’s small airstrip to Goff and Bonnouvrier’s front door, there are so many zebras, including the endangered Grevy’s, that they almost start to seem banal. The white and black rhinos, fewer in number but visible even without binoculars, never do.

For most tourists to this part of the world, animals are the first order of business; the people, whose lives can be hard, are often ignored. Food insecurity, long a problem, has been intensified by a historic drought that began in 2020 and may be abating only now. While building their 4000-square-foot home, Bonnouvrier and Goff realised that being a good neighbour isn’t just a nice thing to do. It can make the difference between life and death.

“Being here is like an onion,” says Goff from the front seat of their Land Rover Defender as we bounce along the rocky main road back from Mayangalo, one of the few small villages that dot the vast reserve. “Every time you peel back a layer, you see there’s more you can do. As they say in Kenya, ‘pole pole’ [slowly]; it is important to take your time and listen before jumping in to fix what may not be broken.”

Doing something involves big things, like the anti-poaching and anti–ivory trafficking campaign Knot on My Planet, which Bonnouvrier and Goff launched in 2016 and which has raised $US15 million to date. And it includes smaller things, such as organising a boys and girls soccer league and rehabilitating run-down playing fields, sponsoring a family of five boys down the road, and setting up a three-acre educational community garden in order to grow indigenous crops using low-impact principles of syntropic agroforestry.

Goff, a gardener, hopes to plant the first quarter after the next rains, with more to follow as water availability allows. She plans to run it on a barter and work-for-credit system, and there are sketches for a gathering area. The government often doesn’t meet the level of need, so if something needs to be done, as she and Bonnouvrier quickly learned, they should do it themselves. It just takes will, stakeholder buy-in, money and time.

Bonnouvrier grew up in Paris, Goff in Florida. “I won’t survive another winter in New York,” she recalls saying. “We have to go somewhere warm.” They traced the equator and landed on East Africa. They’d climbed rocks together and slept under stars, but they needed advice about where they were headed. Their friend, fashion stylist Sarajane Hoare, had spent lots of time in Kenya, so she put together an itinerary.

Hoare’s suggestions had included a more classic, luxury safari camp, with polished mahogany and staff with nametags. Not the couple’s scene. Next on her list was Elephant Watch Camp, on the bank of the Ewaso Ng’iro river in the arid Samburu National Reserve, about 50 miles north of Lewa. Draped in colourful canopies, with woven coconut-leaf mats and riotously decorated outdoor showers, it has more of a hippie sensibility and is staffed almost entirely by the Samburu people, who live on the reserve with their herds of livestock. Because of its proximity to the river, a crucial water source, it’s also the only large, unfenced camp on the reserve, so leopards and lions will often wander past the tents, leaving guests to wonder why they heard such loud snorting outside their door in the middle of the night.

Elephant Watch is run by Saba Douglas-Hamilton. Kenyan by birth, Scottish and Italian in origin, she is the daughter of the elephant researcher Iain Douglas-Hamilton, founder of the conservation organisation Save the Elephants. Goff and Bonnouvrier clicked immediately with Saba and her husband, Frank Pope, a lanky former science and environmental journalist with a degree in zoology who is now Save the Elephants’ chief executive. Douglas-Hamilton and Pope led them on a vigorous hike the next day and they fell in love with what they saw, despite the obvious challenges.

“2014 was a very bleak time,” recalls Douglas-Hamilton. The second big cycle of the ivory trade had started in 2008, largely propelled by demand in China, she says. Save the Elephants estimated that if nothing were done to stop the poaching, wild African elephants would die out in a generation. It would be cataclysmic to a wilderness ecosystem that depends on their movement and complex habits.

Save the Elephants had already worked on one anti-poaching communications initiative, directed at Chinese consumers, featuring NBA star Yao Ming. The conservation community in East Africa is a combination of foreign and Kenyan government aid – each with its own bureaucratic hurdles – for-profit tourism and privately funded non-profits. The decentralised nature of the conservation movement, which has a variety of funding models, makes it difficult to move quickly and speak with one voice. The Obama White House was pressuring for a ban on the ivory trade, too, but the rule didn’t go into effect until June 2016.

Bonnouvrier and Goff had another thought: Instagram.

As the two went home to brainstorm, and commission the branding agency You and Mr Jones, the firmament started to move. In 2014, China began destroying its existing stock of ivory and banned the selling and processing of ivory at the end of 2017. In April 2016 came the country’s largest ivory burn to date. Knot on My Planet launched five months later, to attract a public less likely to be following political news. Fronted by the Dutch model Doutzen Kroes, a DNA client, it started on social media with fashion personalities tying knots and hashtagging the organisation. (The name puns on the idea of tying a knot to remember, also linked to the idea that an elephant never forgets.) Raf Simons tied a knot in his first video post after becoming chief creative officer of Calvin Klein (today he is co-creative director). Linda Evangelista, another DNA client, reunited “the trinity”– herself, Naomi Campbell and Christy Turlington – for the first time in years to tie a big black bow for photographer Patrick Demarchelier.

To monetise their efforts, Bonnouvrier and Goff approached big-money brands. Tiffany & Co. agreed to auction a one-of-a-kind, gem-studded elephant brooch in the spirit of Jean Schlumberger, and then-chief artistic director Reed Krakoff designed a more accessible silver model. They gave 100 per cent of the proceeds to the Elephant Crisis Fund, a joint initiative of Save the Elephants and the Wildlife Conservation Network. (Leonardo DiCaprio’s foundation Re:wild was a founding donor.) Since 2018, Loewe has offered limited-edition elephant purses with beading by Samburu women. Canadian department store chain Holt Renfrew launched a fundraising initiative with shopping events. Thanks in part to these combined efforts, poaching is no longer the leading cause of death of wild African elephants.

Bonnouvrier and Goff also brought Tiffany executives to Elephant Watch. Once they had 45 people in tow, including Kroes and a group of Asian celebrities and influencers that included the Chinese actor Liu Haoran. “We set up a bush camp, and I was like, this is going to be Fyre Festival,” Bonnouvrier recalls. “We sold these people on a trip, and they had mattresses stacked up in the bush two days before people were arriving.” Talent showed up with hair and make-up teams and security, and requested diesel generators to power 24/7 internet connectivity. Somehow they made it work.

This story appears in the December issue of WISH Magazine, out on Friday, December 1.

“They were change-makers,” says Douglas-Hamilton. As Pope prepares for a flyover to track elephants moving through the reserve – studying their behaviour is a core mission of Save the Elephants – he shows me the three light savanna planes paid for by Knot on My Planet and the Elephant Crisis Fund. High in the air, just outside the reserve’s borders, we can see the manyattas, small camps used by the Samburu, scattered in the bush. Each has inner and outer rings of thorns and brambles to keep out big cats, hyenas and wild dogs. Though there has been recent rainfall, the ground is baked hard and dry. “There are no soft edges to life here,” Douglas-Hamilton says later.

Elephant birth rates are on the rise again but humans are vastly outpacing them – population growth in East Africa is double the global average. With more people comes more livestock, which causes elephant movements to change. When these conflict with settlements, the elephants can cause destruction. In addition to engaging local women to watch over existing pathways, Save the Elephants has shifted its educational mission to human-elephant coexistence.

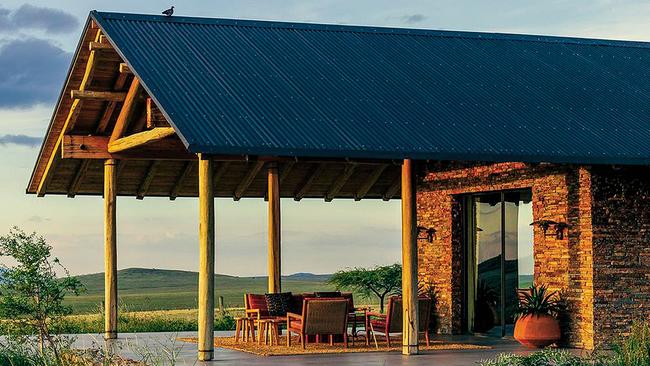

The house in Kenya was the first time either Goff or Bonnouvrier had built something from nothing. It was brought to life on a cocktail napkin by architect Mimi Madigan, a friend and neighbour of the couple in Gallatin, New York, where they both have houses, with a Scandinavian-style knack for making minimalism feel welcoming. The couple wanted something low-key, with lots of outdoor space and big views.

The kitchen would be its centre of gravity. There would be one oversized guest bedroom, but if they wanted to host larger groups there was always Lewa House, a safari camp about a half-hour drive away. With bungalows built in a whimsical, almost Gaudí-esque style, the complex belongs to Calum and Sophie McFarland. Sophie’s family used to own the land that Lewa Conservancy now occupies.

The house might have been simple on paper, but in process it was not. Organising the almost daily Zoom calls for a creative team spread out over four time zones was already a feat: interior designer Katie Lockhart called in from Auckland; landscape architects Michael and Chloé Humphreys are based in Barcelona; Ben Jackson, whose firm Ironwood Africa acted as general contractor, was usually in Kenya; and the others were in New York. Bonnouvrier and Goff wanted to capitalise on the panoramic views of the savanna, which meant terraforming at just the right level where Lewa’s elephants and rhinos would be visible on the other side of the fence without their house lording it over the community, which is made up mostly of small farmers and herders. Jackson was able to truck in plate-glass windows so huge, at roughly 5-by-8 feet, that they had to be special-ordered from Mombasa. They were brought through the Ngare Ndare forest, skirting cliffs and drops and charging up steep curves to arrive at the job site in one piece.

Much of the house, including the local volcanic Isiolo stones that cover the facade and the massive wrought-iron window casings, was handcrafted by artisans from Jackson’s company. He lived on-site in a tent during most of the construction. “We’d speak to him on WhatsApp and be like, ‘What’s that noise?’ and he’d say, ‘Oh, it’s a lion’,” Lockhart recalls.

They broke ground during Covid travel restrictions, so Bonnouvrier and Goff re-created the floor plan, on a 1:1 scale using ropes and wooden stakes, in the field at their house upstate. They furnished it over a year-and-a-half. It took two shipping containers to get everything over, from the George Nakashima table, now in the dining room, to the brass sconces, sourced from a 1950s movie theatre in Rome, for the walls of the dining room and guest bedroom.

Even before the house was finished, Jacob Akitela, a Turkana elder from the community who watched over the land for the previous owner, had been hired to watch the gate. But he was no longer young and needed support. The drought had fully taken hold, depleting herds of livestock and leaving people starving. Douglas-Hamilton had been rotating positions at the camp to try to spread the jobs around – instead of her usual team of around 40 full-time employees, she was providing some form of work to 120. Still, there were people left with no means of support.

One of Elephant Watch’s managers recommended three such men, Samwel Lepina, Yiai Lekoyan and Ntawas Lengamunyak. On the first day I visited, they were clustered around a table in the afternoon being tutored in reading, writing in English and Swahili, and mathematics. Once the household was set up and Goff had hired a few local women to help run it, she learned that not everyone was literate, so she and Bonnouvrier hired a tutor and offered lessons to anyone on their staff who wanted them. Five raised their hands.

There is plenty to do around the house: maintaining the kitchen garden for Goff, Bonnouvrier and the year-round staff; making sure the transplanted grasses and acacia trees are taking root; getting staff members’ kids to the doctor when they fall sick; ordering bunk beds for the five boys down the road, and making sure they are eating and attending school; and keeping the three Land Rover Defenders in working order. It’s almost a village unto itself, and for Goff and Bonnouvrier, along with the elephants and the larger community, it’s the raison d’être of their life in Kenya.

The night before our last day together, the staff had a mutton barbecue. Everyone was gossiping about a rumoured future cattle raid by rival Turkanas when the car from Lewa House came by to pick up the photographer Romain Laprade, who was lodging there. The driver, David Karamushu Jappes, a Maasai man who grew up nearby, got out and swapped stories with Lepina, Lekoyan and Lengamunyak. “You know the Samburu are really something,” Jappes says after a lull. “They’re observers of the stars. They knew before anyone else that the big drought was coming. You see that star up there?” he asks, gesturing to the brightest one. “That’s Venus. You see how it’s a kind of pinkish colour? The Samburu would tell you it means hope.”

This story appears in the December issue of WISH Magazine, out now.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout