Pact with China an ‘act of submission’ for Pope

The renewal of a secret deal between the Vatican and China has come at an embarrassing moment for the Holy See.

The renewal of a secret deal between the Vatican and China on the joint appointment of bishops has come at an embarrassing moment for the Pope, fanning international criticism of what has been characterised as moral appeasement on the part of the Holy See.

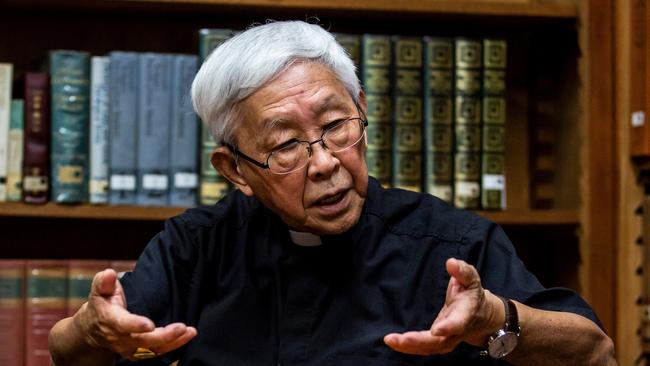

The announcement came on the day that President Xi consolidated his dictatorial powers at the climax of the 20th Chinese Communist Party congress and four days before the reopening of the trial of Cardinal Joseph Zen for helping to fund the legal costs of pro-democracy activists in Hong Kong.

The agreement, signed in September 2018, was intended to unify China’s 12 million Catholics and enable members of an underground church loyal to Rome to practise their religion freely. Critics said that it had merely increased the influence of the state-controlled “patriotic church”, which was founded in 1957 and appointed bishops without reference to Rome.

Bernardo Cervellera, a missionary priest in Taiwan, said: “It takes a lot of optimism to find something positive in this accord. It has resulted in the appointment of just four bishops in the last four years. The Vatican insists there were six, but two were appointed before the agreement came into effect.”

The priest, who directed the Vatican’s Asia News agency for 18 years, said the church was more divided than ever and the Communist Party was using the secret terms of the deal to convince the faithful that the Vatican had fully endorsed China’s position.

“The underground church is under great pressure. Priests have been leaving to work in factories or as farmers because they don’t want to sign an act of submission to the regime,” Cervellera said. “Many of the bishops of the clandestine church are under house arrest, under 24-hour surveillance or in prison. There have been just four new bishops and the country needs 40. The problem is that the members of the underground church have to declare their support for socialism, the Communist Party and Xi.”

Catholics who refuse to register with the official church face reprisals such as being cut off from phone apps used for most daily purchases in China.

The Pope has been criticised for his failure to defend human rights in China or speak up for his own cardinal, who this week saw the charges against him reduced from working for foreign agents to failing to register a charitable organisation.

Asked about the case last month, the Pope said that he could not characterise China’s behaviour as anti-democratic. He said Zen, 90, “said what he felt, and you can see that there are limitations over there”.

Cervellera said Zen’s treatment followed a standard Chinese formula: accusations in a newspaper, then arrest. “In this case they didn’t realise what a hornets’ nest they were stirring up. The whole world has criticised them,” he said.

The Vatican was one of the few organisations that failed to react, said Sandro Magister, the Vatican correspondent for L’Espresso. The struggle between Rome and Beijing involved two unlikely and unequal monarchies, he said, while Francis had an authoritarian approach to diplomacy and had dispensed with experts on China.

“The Pope has called a synod [church assembly] to transform the church into a kind of permanent synod. It’s one of the contradictions of this pontificate,” Magister added. “Xi and Francis represent two absolutisms.”

Cervellera said that the Pope was sticking to the deal because it had established communication with the Chinese Communist Party for the first time in 70 years. Tensions between the US and China may also have contributed. “I think the Pope doesn’t want to be crushed between these two powers or for the church to be seen as western, which it is not,” Cervellera said.

Compromising with oppressive powers is nothing new for the church. Humiliating pacts were the order of the day in the Cold War, when the church came to terms with communist regimes in eastern Europe.

Michael Sheridan, the author of a history of Hong Kong, said Francis was making the best of a weak hand. “The Pope has a dilemma because China practises hostage diplomacy and the Vatican has little bargaining power,” he said. “The church thinks long term and has to keep all its Chinese flock in mind. Sometimes silence is its only weapon.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout