Party of one: China’s ‘Godfather’ moment as he achieves Xiplomatic immunity

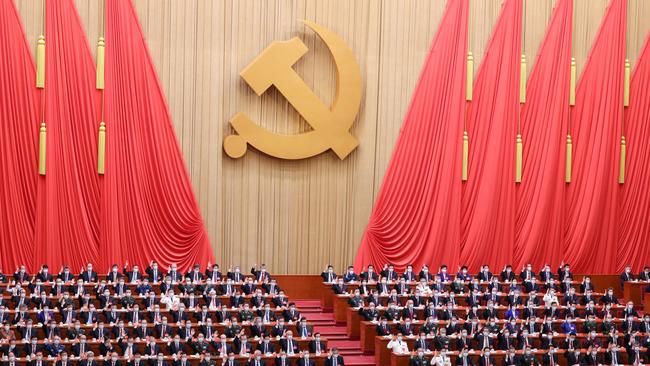

It’s the enduring image from the CCP’s 20th congress. The total lack of empathy for Hu Jintao underlines the cultural chasm between the Leninist party and traditional Chinese values. And the message was clear.

China is a socialist country of people’s democratic dictatorship … Let us harness our indomitable fighting spirit to open up new horizons for our cause.

– From the work report of Chinese Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping to the party’s 20th national congress

We all know now where China is heading for the next 10 years at least. Even more deeply, more fervently, into Xi-country, whose horizons are becoming boundless.

The enduring image from the CCP’s 20th congress that finished last weekend will be that of general secretary Xi Jinping’s dismissive demeanour as his perplexed-looking 79-year-old predecessor, Hu Jintao, who had been sitting next to him in the front row, was led out of the closing ceremony, for reasons that may never be revealed.

The lack of empathy shown to Hu, his white hair signalling his irrelevance compared with the overwhelmingly black-dyed new power elite in their 60s, including Xi, underlined the cultural chasm between the Leninist party and traditional Chinese values that venerate the elderly.

Xi’s steely disregard has been compared with the style of a mafia boss, with which he is acquainted since he has listed The Godfather among his favourite films. Party leaders conventionally worry that to show emotion – or to solicit support, say, by making their speeches entertaining – is perceived as demonstrating weakness.

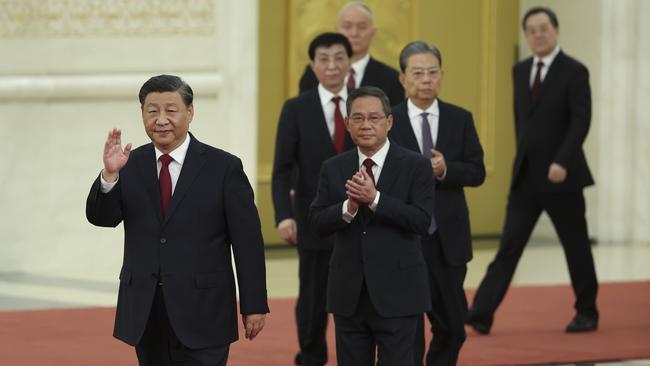

Xi filled at the congress the four slots he opened on the party’s top body, the seven-man politburo standing committee, with diehard personal loyalists led by his former chief of staff, Li Qiang, who as Shanghai party secretary had presided over that city’s chaotic zero-Covid lockdowns, and will now become the next premier. The four are all over 60, thus none are conventionally deemed young enough to be eligible successors to Xi in five years.

So Xi seems set to continue for another 10 years, until 2032, at least. The congress message was clear: the world is turning so sour, we require a stern and ideologically robust helmsman to steer party and country for a further generation.

At the congress, Xi buried for good the cross-factional meritocracy that had been developed under Deng Xiaoping to prevent further Mao Zedong-style descents into dictatorship. The convention – that those aged 67 or under would stay in office, those over 68 would retire, and that top jobs would be limited to two terms – was abandoned.

Premier Li Keqiang and politburo standing committee member Wang Yang, both 67, and Vice-Premier Hu Chunhua, aged 59, all members of Hu Jintao’s tuanpai, or Youth League faction, were ousted.

Xi, who is 69, packed the party’s central committee with personal followers, replacing 68 per cent of full members, compared with 41 per cent turning over at the last congress. Members of ethnic minorities were almost halved. The governor and party secretary of the central bank, the People’s Bank, were also stood down, although aged 64 and 66.

An official report noted that in choosing new leaders, some of the “vetters” focused on “whether they were brave and good at fighting against the US and Western sanctions and safeguarding national security.”

Those promoted under Xi have almost all worked with him, or at least in the same regions – inevitably infecting decision-making with court politics.

On Xi rolls, atop what he calls “the wheels of history”, into a third five-year term that implies, as China expert Ian Johnson says, not so much stability as “an ossification of the political system”, with advisers telling him what he wants to hear.

The work report that Xi issued to the congress was titled “Hold High the Great Banner of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics and Strive in Unity to Build a Modern Socialist Country in All Respects”.

David Bandurski, director of the China Media Project, explains that as with all formal CCP events, the congress is “about keeping the cards close, not laying them on the table. It is a carefully scripted drama” that elevates the power and ideas of the party and its leader, whom he appropriately describes as a “spirit-person”.

Work report rhetoric, and the embedded slogans, are not to be confused with parliamentary-style policy statements or strategies. They are, rather, as Lancaster University Professor Zeng Jinghan explains, “a means of focusing attention and exhorting to action”.

Xi’s report highlights his own special concerns – ideology, history and education – stressing in it that “the most basic aim of education is to foster virtue … We will encourage our talent to love the party”. He defines ideological work as “forging the soul of a nation”. And such history is not in the past. It is, as Bandurski says, a political text drafted by the party.

Most importantly, Xi’s new report stresses that the party, and thus the People’s Republic of China, which it owns, is staying the course set with his “decisive” – as it was titled – 19th congress report.

No backtracking, no “resetting”, no sign of stepping back from the “zero Covid” policy that keeps China locked up. Instead, the party is battening down the hatches against an increasingly wary world as it tightens its own grip on every institution in China, and pursues China’s global “rejuvenation” with Xi as its core.

Xi’s New Era is also, however, now that of Peak Party, as it enters its second century, and of Peak Economy for China. That reality reinforces Xi’s need to speed efforts to ensure the world becomes safe for the party while it still retains the leverage, especially by weaponising its economic ubiquity, to get results.

“Common prosperity” – viewed as Xi’s core current domestic program, favouring public over private sector – has only seven mentions, but they set the tone about the economy. Liu Shangxi, the president of the Chinese Academy of Fiscal Sciences, is cited by Australian Sinologist David Kelly as explaining that “common prosperity” presents a dilemma – “the economy needs focus on efficiency, while society needs to focus on fairness. What’s to be done?” Xi gives no answer.

The word for “security” is used 91 times in the work report, and “economy” 60 times. “Battle” gets 46 mentions. “Political reform”, once given a special section, has gone altogether.

Andrew Batson, of Gavekal Research, sees “the balance of priorities tilting toward security and away from growth”.

The Chinese stockmarkets all plunged when they began trading after the congress, anticipating tougher times ahead as a result of party policy, worsened by contracting exports to major markets, and with the key sectors of property and consumption failing to revive.

Xi wants to “speed up efforts to achieve greater self-reliance in science and technology”, from which he is seeking “better strategic input”, and to “ensure the security of food, energy and resources as well as key industrial and supply chains” through such self-sufficiency. This points to an intensification of what European Chamber of Commerce in China president Joerg Wuttke has called “ideological constraints and uncertainties” producing an unpredictable climate for business. Deng introduced an era of “reform and opening up”. Vestiges remain of the former, but the latter is fast vanishing, while demographic decline compounds the economic challenges.

This congress has taken place, Xi’s work report states, as “the world has entered a new period of turbulence and change”. It underlines Xi’s hallmark governance style, of launching campaigns – such as against disloyalty, often branded as corruption – then institutionalising them to seal in and extend their value to him.

Another example is the “all-out people’s war” against Covid outlined in the report, which has produced the traffic-light app that is already being used to confine to their homes people perceived to be politically troublesome.

The PRC, Xi says, has been confronted with “external attempts to blackmail, contain, blockade, and exert maximum pressure”. His listeners all know he is talking about the US, which he also brands – without naming it – as “hegemonic, highhanded and bullying”. The answer, he says, involves – characteristically for the party – “focusing on internal political concerns”. Former foreign minister Qian Qichen once explained pithily that for the PRC, “foreign policy is the extension of domestic policy”.

Xi proclaims in his new report: “We have shown a fighting spirit.” Since the report, former ambassador to Australia Ma Zhaoxu, now a vice-foreign minister, has reinforced the need to evince that fighting spirit also externally, as directed by Xi Jinping Thought on Diplomacy. The new champion of this Xiplomacy will be Wang Yi, appointed to the politburo although aged 69.

Xi says that when he was elevated, the party had suffered “weak, hollow and watered-down” leadership, with some “lacking confidence in the socialist political system.” In response, he says, “we rolled up our sleeves and got down to work … to carry out a great struggle”, to use one of his favourite words. “We have placed an emphasis on political commitment in selecting officials … There is no end to theoretical innovation … (but) we must never waver in upholding the basic tenets of Marxism.”

The “Chinese path to building a strong military is growing ever broader”, he says, with key goals set for the centenary in 2027 of the People’s Liberation Army – which is the party’s army, not the nation’s. Despite speculation, there is no evidence that these 2027 goals are yet led by seizing Taiwan.

Xi vows to strengthen party-building in the PLA, and to deepen “the system of ultimate responsibility” that rests with the chairman of the Central Military Commission, who happens to be … Xi Jinping. He recognises that a capable fighting force requires more than loyalty. It is also the intensification of military training that will enable China’s “heroic fighting force” to “win local wars”, Xi says.

Xi praises the United Front, the party’s “effective instrument” to advance its interests by influencing or controlling networks and key individuals both inside China and overseas.

He pledges to “strengthen our work … to encourage all the sons and daughters of the Chinese nation” – meaning all people of Chinese ethnicity, wherever they are born – to form “a powerful joint force for advancing the rejuvenation of the Chinese nation”. This further involves developing China’s discourse system to “present a credible, appealing, and respectable China”.

Underlining the disinterest of Beijing in what Taiwanese people, as well as many Hong Kongers now think, Xi continues to assert that the One Country, Two Systems formula remains not only relevant for subjugated Hong Kong, but also for “reunification” with Taiwan, where 90 per cent of people polled consistently stress its irrelevance.

Xi – who often advances a form of ethnic race theory, with the so-called Han at the top of the tree – insists about Taiwan that “blood runs thicker than water” – a generalisation that excises the 600,000 indigenous peoples of Taiwan, which, Xi states coldly, “is China’s Taiwan”. A worst-case scenario would be to opt for a form of “vacant possession”.

Religions in China “must be Chinese in orientation” and must “adapt to socialist society”, Xi insists. Party members are required to be atheists.

There are 97 million party members, most of them today officials and managers. Just 27 per cent of the congress delegates were women. Xi appointed no women to the new 24-man politburo, and none has ever joined its standing committee in the party’s 101 years. Party members, already compulsorily answering daily hour-long online questionnaires via their Xuexi Qiangguo apps, must also now undertake programs on “the party’s new theory … to build it into a Marxist party of learning”. Their attentiveness will be reinforced by “political inspections” and “follow-up rectifications”.

As usual, some of this will cascade down to all government officials – “We must adhere to the principle of the party supervising officials,” Xi insists, “to ensure they are politically reliable.” Businesses won’t escape either: “Party-building will also be stepped up in mixed-ownership and non-public enterprises … trade associations, academic societies and chambers of commerce.”

The party cannot now return to its conventions to restrain leaders, and the chances of an orderly eventual leadership succession have been sharply reduced.

Xi has raised the stakes. It’s not now a game anyone can easily exit or stand aside from, however distant from China itself, as even Solomon Islanders have recently learned. So, faites vos jeux – place your bets before Xi finishes rolling the dice.

Rowan Callick is an industry fellow at Griffith University’s Asia Institute.